A History of the Breton Stripe

Fresh, nautical and undeniably chic, la marinière worn by the sailors in the French Navy is the shirt we call the Breton stripe. For over 150 years these stripes have been seen on board the ships of the Marine Nationale along the Brittany coast. But how did these stripes go from the bracing decks of Brittany seafarers to fluttering crisp and clean on our domestic clotheslines? The Breton’s route from sailor to landlubber is an interesting one.

French sailors in Breton stripes.

The ever-present blue and white stripes are due to an act of French Parliament decreeing that the striped knit or tricot rayé become part of the uniform for all naval seamen based in Brittany. Penned by Admiral Hamelin, the Minister of Marine in 1858, the official bulletin of the French Navy stated, “The body of the shirt will count twenty-one white stripes, each twice as wide as the twenty to twenty-one indigo blue stripes.” Mid-1800s France was still a proud naval power under Napoleon III and rumour has it that the stripes’ numbers represented each one of his Uncle Bonaparte’s sea victories over the British. The truth is probably less bold. The alternating bands probably originated because technical innovations in the 19th century simply made the knitting of stripes easier. The ability to knit in the round meant the Breton could be woven into a snug, seamless tube – free from buttons, seafarers wearing the sweater wouldn’t get snagged on the rigging or fishing nets. Whether the stripes came about from pride or practicality the contrasting colours made the unfortunate men who had fallen overboard much easier to spot in the waves.

Up until Hamelin’s 1858 ruling, regulations for the naval uniform applied only to the officers; sailors boarded their assigned ships in their own rag-tag clothes. After the decree, the striped look was worn only by the crew and quartermasters, not officers. The stripes relegated those who wore it to the bottom of the ship’s hierarchy and soon negative connotations ensued. Even today those officers who once toiled through the ranks in their blue and white stripes instead of graduating unscathed from naval academies are labelled by other officers as zebras.

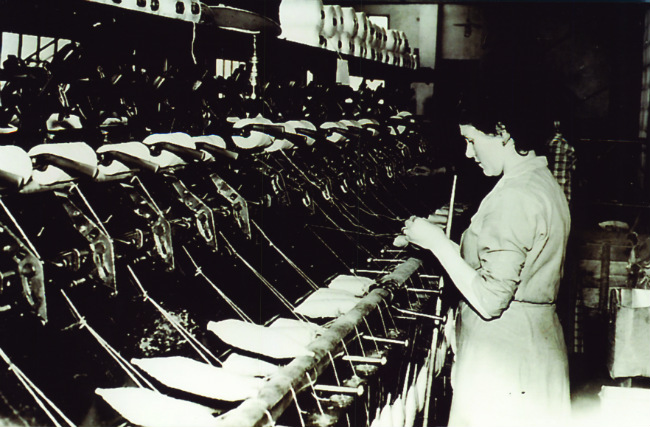

A work at the looms of Saint James. courtesy of Saint James

Although the French Navy’s official sweater was quickly copied by most fishermen and seafarers in the north of France, including the onion sellers leaving from Brittany’s ports, the striped look at the time was not considered remotely stylish. Michel Pastoureau in his 2003 book, The Devil’s Cloth: A History of Stripes tells how wide stripes were originally worn by jesters, wandering minstrels, madmen and lepers. Jailbirds were banded in black and white to be easily distinguishable from civilians; cartoonish shorthand had burglar’s wearing the wide horizontal bars; and the combative push-pull of the Danse Apache was played out in stripes. In other words, stripes were worn by the marginalised. But for those living in the margins, there is a certain amount of freedom to be enjoyed – rules mean little when you’re living the life of a vagabond male.

Coco Chanel in Breton stripes

This masculine freedom was not lost on the innovative designer Coco Chanel; freedom of the female form was something that compelled her. During the Great War, Chanel watched the fishermen in their sailor-inspired Bretons at work along the coast near Deauville. Taken with their look, Chanel adapted a short smock-like marinière for her 1917 couture collection. Her ‘garçonne look’ – a modification of contemporary menswear patterns for the female form – was seen on women now happily liberated from the heavily corseted fashion of the Belle Époque. Chanel is credited in saying, “Luxury must be comfortable, otherwise it is not luxury.” By borrowing from la marinière, Coco heralded an androgynous image of female independence and freedom.

Chanel’s practical, jersey-knit separates soon found themselves in the lexicon of urban chic. Her Breton was stylish, expensive and for the time an excellent example of trickle-up fashion – trends from the street or working class taken over by the affluent. However, it wasn’t long before the sailor shirt was seen on avant-garde figures like Jean Cocteau and Pablo Picasso. Pastoureau states in his book that a nonconformist zebra like Picasso never missed an opportunity to exhibit himself in stripes. In 1952 renowned photographer Robert Doisneau captured the great iconoclast wearing his Breton shirt while working for his daily bread.

The Breton stripe was a big hit in the post-war 1950s

Counter Culture

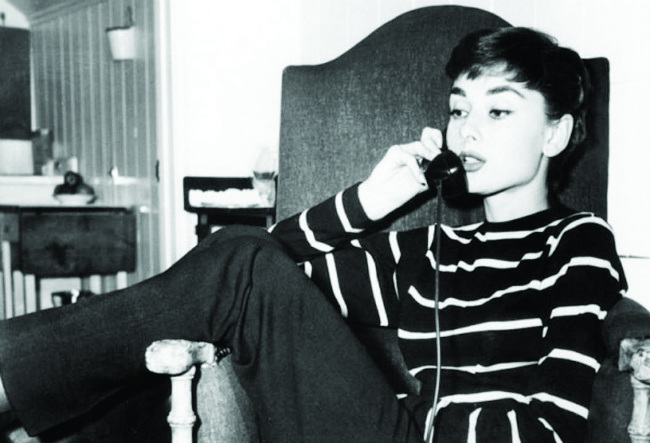

After World War II a huge generation gap developed. When rationing finally ended there were more goods in the shops and the hitherto-unheard-of teenager had buying options. Kids didn’t want to be stuck in their parents’ age – it was their time to be modern. They took the Breton and paired it with rolled-up jeans. The image of the sailor as footloose and free mixed well with the bohemian vibe of the time. In the ’50s and ’60s the striped shirt was popularised by the Beatnik counter-culture. French cinema, buoyed by the New Wave – Nouvelle Vague – embraced the sailor look wholeheartedly. Breton stripes graced movie screens and became synonymous with the time. The always-gamine Audrey Hepburn was frequently captured wearing the flattering sailor tee; Brigitte Bardot artfully lounged in the nautical stripes; and Marcel Marceau’s mime, Bip, was never seen without his skin-tight version of the sailor suit. For Alfred Hitchcock’s To Catch a Thief, costume designer Edith Head made Cary Grant look suave and just a little outré in her adaptation of a grey striped Breton topped off with a dotted kerchief.

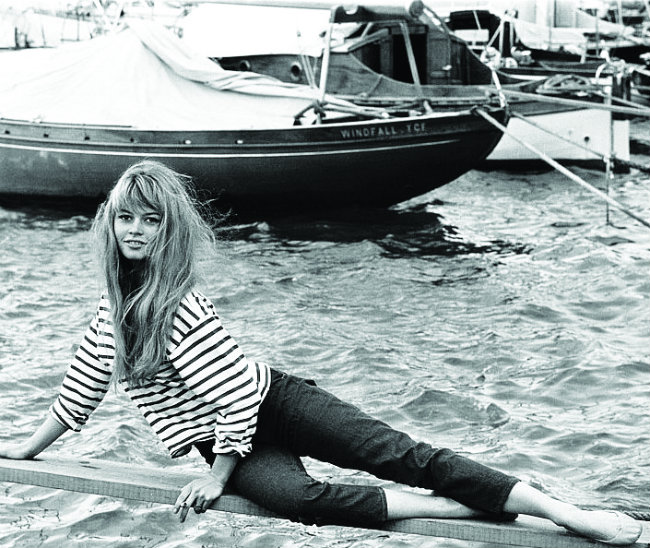

Brigitte Bardot wearing Breton stripes

Audrey Hepburn rocking the Breton look

Inspired by Jean Seberg’s tomboy Breton in Jean-Luc Godard’s 1960 Breathless (À Bout de Soufflé), Yves Saint Laurent introduced the classic into his premier collection. Jean-Paul Gaultier is another designer who used the Breton to his advantage. Since the 1980s, Gaultier has been a virtual ambassador for the look and has used the bold stripes in all forms including the torso motif for his cologne Le Male. In 2011 Karl Lagerfeld dressed Les Bleus – the French football team – in the Breton stripes for their away kit. Clean, sober and classy, the short-lived kit was said to embody the values of the French team while abroad. It was seldom used but much commented on.

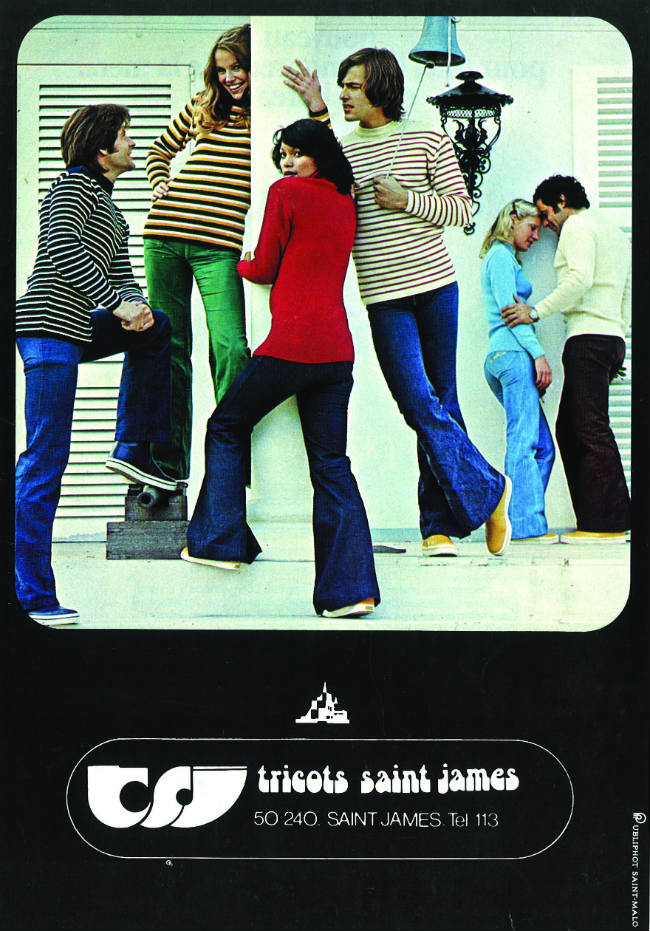

Tricots-Saint James advert from the 1970s. Courtesy of Saint James

Apart from being called the Breton, the striped sailor jersey has earned many names over the years, including la marinière (the sailor), le pull marin (the sailor sweater), tricot rayé (the striped knit), and le chandail, which today translates literally as ‘sweater’. Chandail has an interesting word history that originated with the French onion merchants. Garlic and onion sellers frequently wore the recognisable blue/black and white jersey of the Breton fisherman. Like the mariners, they realised the jaunty stripes made them easier to identify. The self-dubbed ‘Onion Johnnies’ left from the harbours of Brittany to ply their wares on the English side of the Channel. The stripes became their trademark at their British ports of call and became synonymous with all things French. Their shirts soon earned the nickname ‘Chandail’, a contracted version of the word garlic merchant, marchand d’ail.

A genuine Breton sweater is knitted on a circular loom with pure, double-twisted sheep’s wool. The resulting extremely tight stitch made it resistant to both wind and cold. Wool has always been highly sought after by seamen for retaining warmth even when wet. The wool’s lanolin adds a touch of waterproofing to keep sailors warm and dry at sea.

On the production line at Saint James. Courtesy of Saint James USA

Making La Marinière

Courtesy of Armor Lux

On land the Breton holds a certain cachet with civilians too because of the excellence of the product and the limited number of manufacturers still involved in making the sweater. Today the true Breton is made by just three principal companies. Tricots Saint-James has been making la Marinière in the Normandy town of the same name since 1889 and still provides the French navy and army with their official sweaters.

Armor-Lux is Saint-James’ biggest competitor, which has been manufacturing the Breton shirt in Quimper since 1938. Orcival was founded in Paris in 1939 and now has its knitting factory in Lyon. All three still make the Breton exclusively in France but the contemporary Breton is seen in different colourways, materials and adaptations. In 2012 Arnaud Montebourg, France’s once-Minister of Industrial Renewal, appeared in an Armor-Lux marinière on the cover of Le Parisien along with the slogan ‘Made in France’ to promote products made at home that have a significant impact on French society.

On the production line. Courtesy of Saint James USA

And what an impact the Breton has! On woman, man or child, on the young or the not-so-young, the Breton embodies the composed, informal cool that goes hand-in-hand with timeless French style. The striped pullover sailed past fashion fads and trends and became an enduring icon. Merci! to original Bretons who wore the nautical stripe.

* Michel Pastoureau. The Devil’s Cloth: A History of Stripes. Washington Square Press, New York, 2003.

From France Today magazine

A contemporary interpretation of the Breton stripe by Saint James. Photo: Melville Emargarita/ Saint James USA

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

By Hazel Smith

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY