A History of the French Circus

Hazel Smith traces the noble antics of acrobats, trapeze artists and clowns, from 18th-century Versailles to the Cirque du Soleil.

Under the Big Top, the audience is excited. Acrobats and aerialists, as bright as birds, will soon delight the crowd. Death-defying tightrope walkers and fire-breathing daredevils will make the crowd gasp. It’s the circus, with a bit of something for everybody, where enchantment and whimsy mix with the mockery and mysterious morals of street clowns. The jangling of the circus organ and a generous lacing of exotica from the four corners of the world complete the picture.

France has been in love with the circus ever since English equestrian Philip Astley impressed Louis XV with the horses, acrobats, jugglers and clowns he brought to Versailles in 1782. Astley and his sons would go on to build the Amphithéâtre Anglais, located where the Place de la Republique is today.

During the French Revolution, the master of Astley’s birds, Antonio Franconi, leased the theatre from his employer and Franconi’s Cirque Olympique became the first French circus. Franconi and his sons made many improvements to their theatre, including setting the diameter of the circus ring at 13m, which remains the standard to this day. It meant it was easy for itinerant performers to transfer their act from circus to circus, plus theatre in the round created an intimacy between the performers and their audience.

Hand coloured and hand tinted sepia photograph of Jules Léotard. © Victoria & Albert Museum

THE MAGIC RING

Within the magic ring, circus-goers witnessed risk and danger, and were wonderstruck at the awesome athletics and the absurdities of the acrobats and clowns. Circuses employed a wide variety of artists from around the world to make the show colourful and appealing. Beside knife-throwers and tightrope walkers were jugglers, stilt walkers, and contortionists. But the original circus draw was trick riding.

Early European circuses were operated by equestrian families dependent on their horses to get them from town to town. The popularity of the travelling circus increased with the advent of train travel, which made it easier to move the equipment and roustabouts needed to pitch the large tents. As time moved on, travelling menageries of exotic species joined the ranks and the lion tamer became a revered new member of the circus family.

IMAGE © Dominique Secher Cirque d’Hiver Bouglione

Roving fêtes foraines, or funfairs, soon popped up on the periphery of Paris. Nomadic encampments of well-worn wooden wagons surrounded the colourful pavilions which featured the wonders of the circus and freaksish sideshows for just a fraction of the admission to one of the city’s permanent circuses.

By mid-19th century, Paris was the centre for circus performances. All specialised in equestrian acts, clowns and acrobats, each appealing to a specific clientele. In 1840, the Cirque d’Été opened, operating during the warmer months for the upper-crust Champs-Élysées crowd. On the cooler side of the calendar was the Cirque d’Hiver, which attracted a diverse local audience. Located on rue Amelot in the 11th arrondissement, this 20-sided amphitheatre opened in 1852 as the Cirque Napoléon.

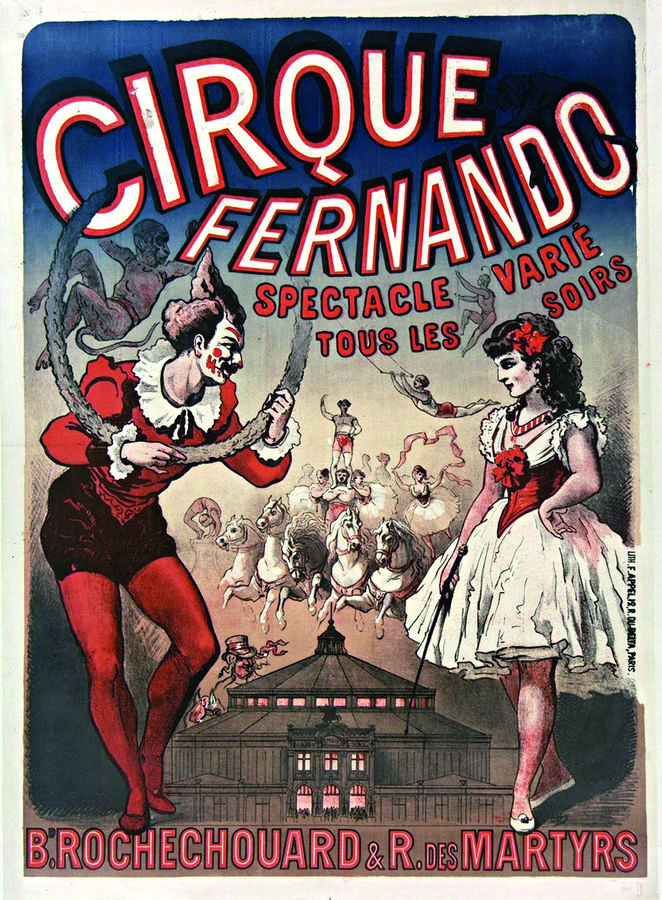

Toulouse-Lautrec’s painting of equestrians at the Cirque Fernando. © Art Institute of Chicago/ Wikipedia

The biggest development in the 19th-century was down to Jules Léotard, he of the eponymous clingy one-piece suit. Léotard developed an act of trapeze bars, ropes, rings and rigging and debuted his gravity-defying show at the Cirque Napoléon in 1859. Léotard was immortalized in the 1867 song, The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze. Today, the Cirque d’Hiver Bouglione, operated since 1934 by the Bouglione brothers, is the world’s oldest circus still in activity and remains a full-service circus with dancers and feats of derring-do.

Cirque Fernando opened in 1875 much to the delight of the Belle-Époque artists of Montmartre, and the likes of Renoir, Degas, Seurat and Toulouse-Lautrec soon became regulars amid the audience of 2,500. The Fernandos gave them free access to sketch the performers at work – for the artists it was a way for them to portray modern life; for the owners it generated considerable publicity.

The famous Trio Fratellini. © Wikimedia

Due to their unconventional jobs, bohemian ways and what were considered by respectable folk to be questionable morals, artists and circus people were kindred spirits on the fringe of society. Edgar Degas painted Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando, Renoir painted the jugglers there, Georges Seurat’s pointillist painting, ‘Le Cirque’, accurately depicts the theatre’s frivolities. Toulouse-Lautrec created many drawings and pastels depicting performances at the Cirque Fernando. For other poster artists, like Jules Chéret, circuses were their bread and butter.

When the Fernando passed into the hands of the popular Spanish clown Gerónimo ‘Boum-Boum’ Medrano, the open-door policy continued and a new flock of artists were drawn to Cirque Medrano, including Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque and Henri Matisse. Picasso was fascinated by the itinerant lifestyle of the acrobats, or saltimbanques, in their bright harlequin costumes and painted them in 1905 during his Rose Period, which is also sometimes known as his Circus Period.

WARNING: CLOWNS AHEAD

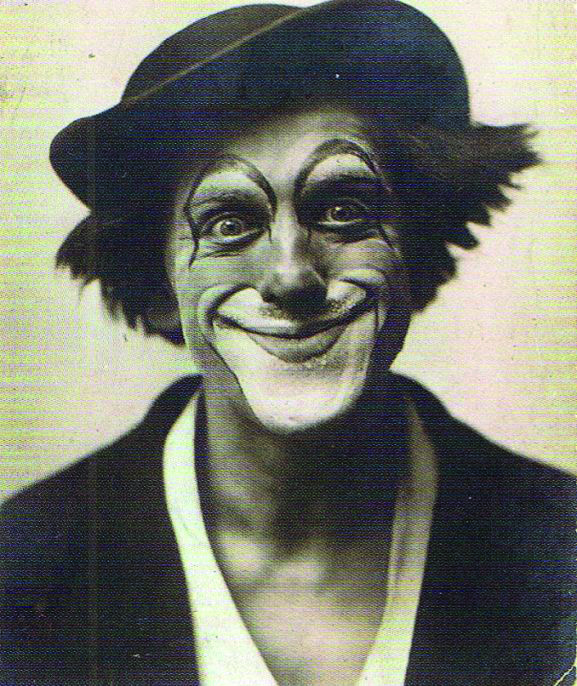

Picasso’s entourage made friends with the renowned clowns Rico, Alex, and Grock. Grock’s act was a clever mixture of pantomime and musical blunders and he was once the highest-paid entertainer in the world. The Medrano, dubbed ‘The Temple of Clowns’, featured many of the world’s greatest, from Gerónimo Medrano himself to Buster Keaton, and launched the extraordinary career of the Fratellinis, stars of the European circus. The building was demolished in 1974 – today, Cirque Medrano is a travelling circus.

Grock in 1904. Unknown author.

The original home of the Hippodrome was demolished in 1897 to be rebuilt in 1900 on the Boulevard Clichy with 5,000 seats, half its original capacity. The new Hippodrome’s inauguration was a colossal event with 200 performers, six elephants, and 50 horses. The Hippodrome held sporting competitions, enormous equestrian events, and when flooded, even simulated epic naval battles. It closed in 1911 because it could no longer fill enough seats, and was turned into a movie theatre, reflecting the evolving tastes in entertainment. The grand age of cinema had well and truly arrived, nudging the circus out of the limelight. Performances were stagnating, with no new innovations seen for decades. Animal rights, also, began to be a concern for the public. The mid-20th century was a time of crisis for the circus and many big names in the business went bankrupt.

Acrobatics at the Cirque Plume. © Cirque Plume 2017/ Benoit Dochy

BACK TO SCHOOL

Federico Fellini is quoted saying that Paris was “the city that made the circus an art”. But for those with a penchant for clowning or the trapeze, there was little opportunity to hone one’s art if not born into a family of entertainers. The 1970s saw the formation of two of Europe’s professional circus schools, both founded by circus performers from legendary French families. Annie Fratellini, from a long line of clowns, founded École Nationale de Cirque in 1975, while the École au Carré was opened by the renowned Alexis Gruss. From intimate family-run affairs to grand to Cirque du Soleil-size, French circuses typically put on up to 1,000 shows a year. In 1981 the French government subsidised the art form, creating a framework to support the robust circus life France enjoys today and securing the country as the world’s centre of circus performance and study.

Today’s circus schools don’t teach elephant tricks or tiger training. Historically, circus animals have been maltreated but France’s attitude has changed toward this. Minister of Ecological Transition Barbara Pompili said in September 2020: “It is time that our ancestral fascination with these wild beings no longer means they end up in captivity.” France will gradually ban the use of wild animals – bears, tigers, lions and elephants – in travelling circuses, but not permanent venues.

AESTHETICS AND ATHLETICS

Inside the Cirque Phenix. © Laurent Bugnet

The modern circus now focuses on acrobatics rather than animals, attracting the crowds with its a spectacle of agility, strength, humour and jewel-bright costumes, all tied together with a unique narrative and an innovative soundtrack.

While the traditional Cirque d’Hiver Bouglione is still in existence with horses, high-wire and human cannonballs, the new circuses of France offer an edgy blend of the circus tradition mixed with the realism of urban culture. The Paris-based Cirque Alexis Gruss advertises itself as being a display of equestrian, comic, and musical paintings. In the latter part of 2021, Le Cirque Phénix will celebrate the women of the circus. France is also the home of the Festival Mondial du Cirque de Demain and the Cirque de Paname in the Bois de Boulogne, an exhibition of light and colour, dance and song with aerial acts and feats of strength.

Some, like Le Zebrè de Belleville, present a more intimate, cabaret-like setting. Promoted as the smallest cabaret circus in Europe, tightrope walkers, trapeze artists and jugglers perform overhead as patrons enjoy a candle-lit dinner.

The Cirque d’Hiver. © Wikimedia/ DXR

Others are counter-culture and radical, like the Cirque Électrique, an electropunk burlesque of buffoonery where the libertines barely remain dressed. Around since 1995, their innovative, experimental performances need to be seen to be believed.

There are circuses around the Hexagon for every taste. Archaos, a pioneering alternative circus set in Marseille, features death-defying stunts such as chainsaw juggling. It’s poetry in motion under the big top of Cirque Plume in Besançon. Acrobats and aerialists make their home at the Nowhere Circus in Amiens, as does the architectural gem, Cirque Jules Verne. Meanwhile, the Festival International du Cirque de Bayeux is forging ahead this year for its ninth season. So it seems, 239 years after Philip Astley entertained the King, the circus remains as important a part of French culture as ever.

Folies Gruss. © Olivier Brajon

From France Today Magazine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

By Hazel Smith

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY