Every Street Sign Tells a Story: A History Lesson in France

France’s streets and squares provide a unique history lesson for travellers. Gillian Thornton digs deeper into the French national identity

Wandering round the historic centre of Chartres, map in hand, I stopped on the river bank beneath an evocative street sign. Rue du Massacre sounded like the site of some awful murder or battle, but no – the strapline on the sign explained that this was the site of a former abattoir. Not far away I found rue des Tanneurs. Both signs are reminders of the noise, smells and bustle of this district in medieval times.

An evocative street sign in Chartres. Photo: Gillian Thornton

Street signs can offer an extra dimension of discovery to the inquisitive traveller, a chance to slip back through time into centuries of French history. I’m sure there must be a Tannery Street somewhere in Britain, though I’ve yet to find it, but I often find its equivalent in ancient French villages and historic city centres.

Rue des Vieux Murs (“old walls”) in Lille. Photo: Gillian Thornton

You don’t need to travel far around the Hexagon to realise how many names of streets and squares are apparently uniquely French. I’ve not yet found a British version of rue des Remparts, so common in France, where many communities were fortified in the Middle Ages – often against the English. And while I’ve seen many a Castle Street and Church Street at home, I’ve never spotted a Well Street (rue du Puits) or an ancient lane named after the village wash house (rue du Lavoir) or the water trough (rue de l’Abreuvoir).

“Rue des Juifs” (jews) in Bourges. Photo: Gillian Thornton

THE PAST IN THE PRESENT

France wears its history on its sleeve with street names that give the past a permanent place in the here-and-now. Dual-language signs provide an in-your-face statement of regional culture, as in Brittany, Corsica and the Basque Country, while creative design can showcase a city’s identity, like the ‘speech bubble’ signs in Angoulême, capital of the bande dessinée (comic strip).

A street named for Hergé, creator of Tintin, in Angoulême

But French street signs don’t only bring social and commercial history to life. A whole cast of characters from politics and literature, science, exploration and the military is commemorated in city boulevards and village squares. And while most of us can identify key figures like General de Gaulle, Louis Pasteur and Victor Hugo, how much do we really know about the others?

Victor Hugo by Étienne Carjat, 1876

Let’s start with those big hitters, though. Two of the most popular figures commemorated in public places are the writer Victor Hugo and the microbiologist Louis Pasteur. Type their names into your GPS and you’ll almost always end up in the centre of town. Author of Les Misérables and Notre-Dame de Paris (The Hunchback of Notre-Dame), Hugo was also a champion of human rights.

Avenue Victor Hugo in Paris. Photo: Fotolia

Pasteur did his bit for the human condition too, launching the first rabies vaccination in 1885 and inventing pasteurisation. Both men, by coincidence, were born in Franche-Comté, and while Hugo’s military father soon moved on from Besançon, Pasteur lived most of his life in Arbois. You may also find yourself walking in the footsteps of one of the first scientists to promote the use of microscopes: chemist, physician and politician François-Vincent Raspail.

Louis Pasteur

France has always put a high value on personal freedom and liberty, hence ubiquitous names such as rue de la Liberté, avenue de la Libération and place de la Résistance. But writers, philosophers and social reformers are showcased too. François-Marie Arouet, born in 1694, could never have imagined the posthumous recognition he would receive in public places under his pen name, Voltaire. His hometown of Ferney, near the Swiss border, was even renamed Ferney-Voltaire in recognition of his work in developing the town out of rough marshland.

Émile Zola in 1895

Many thoroughfares across the country are named after writer and philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who was born in Geneva in 1712. A key philosopher and writer of the Age of Enlightenment, Rousseau believed that government should be ruled by the people and his writings strongly influenced the French Revolution. Similarly, streets in many towns are named after Émile Zola. Born in 1848, he spent his childhood in Aix-en-Provence and went on to become one of the most important political journalists of the age.

Émile Zola street in Villeurbanne. Photo: Alamy

Jean Jaurès

Many streets also bear the name of Socialist party leader Jean Jaurès, founder of L’Humanité newspaper and sadly assassinated by a young French nationalist in 1914. Watch out, too, for novelist André Malraux. France’s first Minister of Cultural Affairs under De Gaulle, he was responsible for saving historic towns and buildings across France in the 1960s, starting with medieval Sarlat in the Dordogne valley.

Sarlat in the Dordogne valley. Photo: Gillian Thornton

Other men are celebrated more locally for contributions of national importance. In the Dordogne valley at Figeac, place Champollion commemorates Jean-François Champollion, the scholar who first deciphered the Egyptian hieroglyphics on the Rosetta Stone in the 1820s. Head south to Béziers and the broad, shady avenue named allées Paul-Riquet commemorates Pierre-Paul Riquet, the visionary engineer behind the Canal du Midi. Béziers was also the birthplace of Jean Moulin, Préfet of Eure-et-Loir, who unified the French Resistance and was arrested by the Gestapo in Lyon.

Place Champollion in Figeac. Photo: Gillian Thornton

You won’t find too many streets named after French kings, although William, Duke of Normandy earns the odd nameplate for his conquest of England in 1066. But politicians are another matter. One of the most commemorated is Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Minister of Finances and ‘Mr Fix-It’ to Louis XIV in the mid-17th century. Colbert set up the network of national studs to breed warhorses and improved both the country’s manufacturing and its economy.

Statue of Pierre-Paul Riquet by David d’Angers on the allées Paul-Riquet in Béziers. Photo: Gillian Thornton

REMEMBERING KEY PRESIDENTS

Fast-forward a couple of centuries and 14 presidents took office under the Third Republic between 1871 and 1940. Many are long forgotten, but town planners have immortalised key players like Adolphe Thiers, first President following the defeat of Napoleon III and the Second Empire at Sedan in 1870 during the Franco-Prussian War. And you’ll often drive down streets named after Léon Gambetta, a Republican deputy from Cahors. A prominent statesman during the Franco-Prussian War, he continued to fight for his beliefs in the Third Republic.

Boulevard Gambetta in Grenoble. Photo: Fotolia

Place Gambetta in Cahors. Photo: Gillian Thornton

Georges Clemenceau

Sadi Carnot, fourth President of the Third Republic, earned his special place in history by being assassinated by an Italian anarchist in 1894, while the ninth President, Raymond Poincaré, led the country from 1913 to 1920, into and out of World War I. The Great War also made a national hero out of Prime Minister Georges Clémenceau, who took office for a second time and was widely lauded as ‘The Father of Victory’. But it is Aristide Briand who takes the prize for serving the most terms as Prime Minister under the Third Republic. He clocked up no fewer than 11 terms between 1909 and 1929, and received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1926.

Charles de Gaulle

The heroes and events of 20th-century conflicts have earned an everlasting place in French towns and cities. Top man is Général Charles de Gaulle, born in Lille in 1890 and founder of the Free French movement with a historic broadcast from London commemorated all over the country in streets named rue du 18 juin 1940.

Place Charles de Gaulle in Paris. Photo: Fotolia

Other military dates that resonate through the suburbs are rue du 11 novembre (Armistice of 1918) and rue du 8 mai (German surrender of 1945). And avenue Verdun ensures that nobody will ever forget the 1916 battle that is said to have claimed at least one young man from every French community.

Avenue George V in Paris. Photo: Fotolia

MILITARY MIGHT

Confused by all those military figures? Well, think World War I for Maréchal Joffre, Commander-in-Chief of French forces on the Western Front and instrumental in securing victory at the First Battle of the Marne in 1914. And the same conflict for Maréchal Foch, Allied Commander-in-Chief in 1918.

Rue Friedland in Angoulême. Photo: Gillian Thornton

Then skip forward 30 years to Général Leclerc, who served De Gaulle in North Africa in 1940 and took part in the Liberation of Paris in 1944. Ever wondered about the man behind the Faidherbe signs? Think Africa again. Louis Faidherbe was Governor of Senegal in the mid-19th century, and set up the new colonial city of Dakar in 1857, future capital of French West Africa.

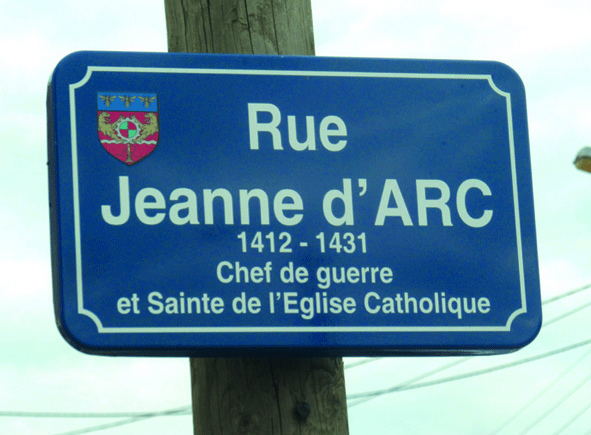

Rue Jeanne d’Arc

And who can forget perhaps the most visible war hero of them all, Jeanne d’Arc? One of the few women now honoured in public highways across France, she was born around 1412 in Domrémy, liberated Orléans from the English in 1428, but was burnt at the stake in Rouen three years later.

Talmont, one of the Plus Beaux Villages de France. Photo: OT Talmont

Proud though the French are of their homegrown talent, great men from other nations can often be found in urban signage. In pretty Talmont on the Gironde estuary, I found a street dedicated to Édouard 1er d’Angleterre, who founded this walled town in 1284. Today it’s one of the most popular among the ‘Plus Beaux Villages de France’.

A street named for Édouard 1er d’Angleterre in Talmont. Photo: OT Charente-Maritime

And in Le Quesnoy, deep in rural Avesnois in the Nord, I came across the surprising place des All Blacks and a conversation-stopping carnival giant in the shape of a Maori warrior. This strategic small town was fortified in the 17th century by Vauban, another popular figure in any index of street names, but fell into German hands early in World War I and was finally liberated by New Zealand forces on November 4, 1918.

The Place des All Blacks in Le Quesnoy. Photo: Gillian Thornton

Statesmen of other nations are remembered too. Many big towns have a boulevard Churchill named after Britain’s World War II Prime Minister Winston Churchill or an avenue President Wilson, a tribute to US President Woodrow Wilson, who led the United States during World War I.

So next time you’re travelling around France, stop and think about the people behind the signs you see – you might be surprised at just how much you learn!

From France Today magazine

A Maori carnival giant in Le Quesnoy. Photo: Gillian Thornton

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY