A New Renaissance: Contemporary Art in the Loire Valley

“Je tourne en rond” – I’m going round in circles – tease the words above the entrance. You don’t say… The cheeky doodle of an arrow looping on itself underneath twists the knife just enough. After meandering in vain up a hill, round narrow alleyways and uncovering a baffling concentration of dead ends I pause in awe (and a little breathless from the climb).

Straight out of a Dalí painting, every inch of the large façade of the elusive Fondation du Doute is overlaid with a patchwork of round, childish squiggles, which upon closer inspection reveal themselves as a pell-mell of jotted-down thoughts, quips, pearls of wisdom and popular sayings. This is the Wall of Words, a puckish installation of 300 tableaux-écritures by the offbeat artist, and mastermind behind the wacky art centre within, Ben Vautier.

Blois – Château royal. Photo: Gillard & Vincent/ CRT Centre Val de Loire

The berserk scribbled landmark is not what your ‘serious’ buffs would expect from the age-old Loire Valley château trail. Just four years ago, they would have been back on the bus, headed for the delights of Chaumont and Amboise after a pit-stop at the Château de Blois – Francis I’s first stab at flamboyant architecture, or “his first pancake,” as our guide elegantly puts it. Emulating the king builder’s love of innovation, and penchant for bold artistic statements, for the best part of the last decade this previously immutable region has experienced a Renaissance of sorts and reinvented itself as a large-scale modern art trail. Art centres have cropped up on its cobbled thoroughfares, fanciful installations deck out the regal halls of its châteaux – even cathedrals have been swept up in this contemporary frenzy. Now more than ever, the Centre-Val de Loire is bent on shedding its ‘frozen in time’ (some might go as far as saying anachronistic) image, and pronto!

The Chateau de Blois’s architecture was, in its time, a radical departure. Photo: Daniel Lepissier

A stone’s throw, when you eventually zero in on it, from the Château de Blois, the Fondation du Doute, with its riot of provocative art and hilarious sculptures-cum-toys could not be further from the historic pile. Yet, its daring and playful pieces offer comic relief and act as an outlandish counterpoint to the castle’s eventful past and most lurid episodes.

Half a century after Francis I tackled the audacious transformation of the castle, the Château de Blois played a decisive role in the Wars of Religion. It was at the royal residence that Henri III had the leader of the Catholic League assassinated in 1588. Catherine de’ Medici died there a year later (peacefully in bed). Rumour has it the empoisonneuse stashed a cache of poisons in the chamber adjoining her apartments. “Complete and utter rubbish,” according to our no-nonsense guide. The cunningly concealed cabinets in the panelling, however, and the pedals hidden in the skirting board to unlock them, invite speculation…

Equally characterful, the Fondation, which doubles as an art school, thrives on excess and is fast becoming the jewel in the crown of the revitalised Loire Valley. The only centre dedicated to the avant-garde Fluxus collective in Europe, it is a treasure trove of works by its key artists (not least Yoko Ono’s wall of naked butts and accompanying video), including a wondrous collection of Ben’s own tableaux-écritures and whimsical sculptures. His rocking duck and tongue-in-cheek graffitied Mona Lisa alone are worth the trek up the hill. Founded in 1960, Fluxus began as a network of artists keen to debunk pre-conceived ideas around form and embrace an irreverent and light-hearted approach to creation; one rooted in chance, humour and child’s play.

Ben’s artwork at the Foundation du Doute. Photo: Marion Sauvebois

Tickling visitors’ funny bone – and wrong-footing them – is the watchword, and everything is designed to ignite your sense of childlike wonder. Venturing into the downright barmy wonderland, you’re invited to let your imagination run wild, push buttons, pull levers and crank up the silliness. Sounds and the explosion of colour everywhere conspire to create a joyous sensory overload. But this is not for the skittish: you approach the bizarre installations at your own risk. Strolling casually past rows of apparently humdrum car doors, for example, triggers a motion sensor and in a fraction of a second the scrap metal bursts into life, complete with hammers banging on the sheets in one cacophonous blast. At least the din has the added bonus of muffling my squeal.

Another sculpture invites hardy guinea-pigs to slip their hand into a mocked-up Bocca della Verità. Beware: a light jiggle elicits borderline erotic groans from the carp-like mouth. Last but not least, a Magic 8 Ball strategically placed by the exit dares the curious to seek its wisdom. I quickly get in line to shake the oracle. For some of my unamused travelling companions though, this cheeky swansong is too zany for comfort and, clearly, the last nail in the coffin.

Just a bunch of inanimate car doors- or so you’d like to think… Photo: Marion Sauvebois

RADICAL PROJECT

Blois is not alone in bowling purists a wrong ‘un on the well-trodden Route des Châteaux. Since 2008, the Château de Chaumont-sur-Loire has carved itself a unique niche in the world of contemporary art by relaunching as The Centre of Arts and Nature; a bold extension of its cultural offering that began with the International Garden Festival in the 1990s. The project was radical at the time and thoroughly divided opinion. The persistent frown and pursed lips haunting the face of one of my companions during our tour tells me it still does. Giving a coterie of visionaries carte blanche to colonise the hallowed halls and parkland of an estate so steeped in royal intrigue was indeed a gamble.

The Chateau de Chaumont-sur-Loire. Photo: E. Sander

Let’s not forget that a conniving Catherine de’ Medici banished her late husband and king’s mistress Diane de Poitiers to Chaumont, after removing the aristocrat from her superior castle at Chenonceau – not such a bad trade-off really, all things considered, what with her handsome earnings taking in tolls from travellers on the river flanking Chaumont.

Stéphane Guiran’s dreamlike field of quartz. Photo: Marion Sauvebois

Fibre artist Sheila Hicks is heading the bill of exhibitors commissioned for the 2017 Art Season, which started in April. Except for a quick peek at Stéphane Guiran’s dreamlike field of quartz, freshly ‘planted’ in the stables, the line-up is still very hush-hush as we trawl around the site on a drizzly March day. But there is plenty to whet our appetite.

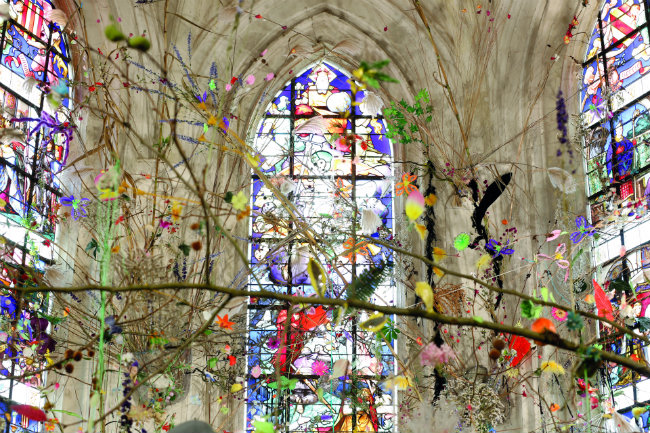

Gerda Steiner and Jorg Lenzlinger’s tangle of branches in Catherine de’ Medici’s chapel at the Chateau de Chaumont-sur-Loire. Photo: E Sander

A smattering of ‘leftover’ installations from years gone by have found a permanent home at Chaumont. Chief among them is the tangle of branches, dreamcatchers and dangling CDs (yes!) overrunning the chapel. While Swiss artists Gerda Steiner and Jörg Lenzlinger’s scintillating jungle knocks the wind out me, it is dismissed by my frowning friend with a terse, “I don’t get modern art.” Each to their own…

Far from detracting from the legacy of the place, this art invasion seems to have loosened guides’ tongues and broadened the scope of the tours (during my visit in 2007 the focus was firmly on the Renaissance) – prompting juicy revelations about the louche past of its last owner, the Princesse de Broglie. The heiress to the Say sugar refineries bought the château on a whim at just 17 in 1875. At the ripe old age of 73 she remarried to Louis-Ferdinand, Infante of Spain, a ne’er-do-well 31 years her junior.

Henrique Oliveira’s coiling tree sculpture. Photo: Marion Sauvebois

A snoop around the outbuildings to behold Henrique Oliveira’s coiling tree sculpture, Momento Fecundo, inspired by Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince, is another excuse to delve deeper into the princess’s rakish toyboy’s seedy antics. Years back, a suspicious-looking white powder bag was discovered in a crumpled riding coat in the barn. Police were called and identified it as an ancient stash of cocaine, “belonging to the ‘Infant Terrible’ no doubt,” says our escort accusingly.

Out in the park, which the de Broglies were instrumental in landscaping to its current glory, we wander past François Méchain’s startling L’arbre aux échelles – rope ladders hanging precariously from the branches of a massive tree – as more nuggets from the irrepressible pair’s riches-to-rags story are doled out. Their taste for luxury was ultimately their downfall. The romance fizzled fast. The castle was repossessed by the State and the princess lived out her days at the Ritz and George V hotels in Paris. The fate of the ‘Infant Terrible’ is shrouded in mystery.

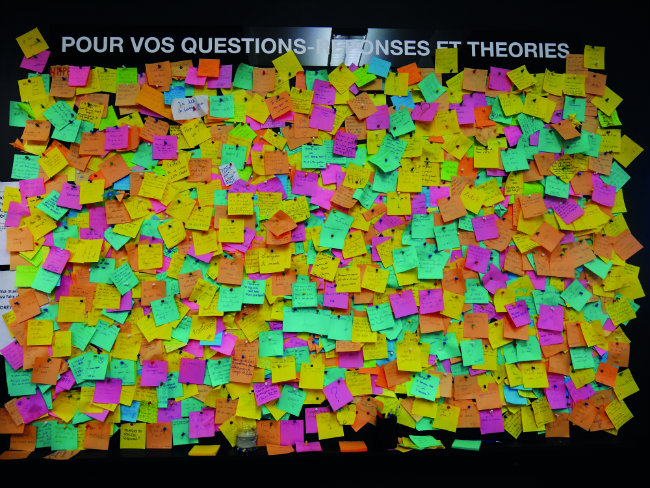

Comments wall installation at the Fondation du Doute. Photo: Marion Sauvebois

OLD AND SHINY NEW

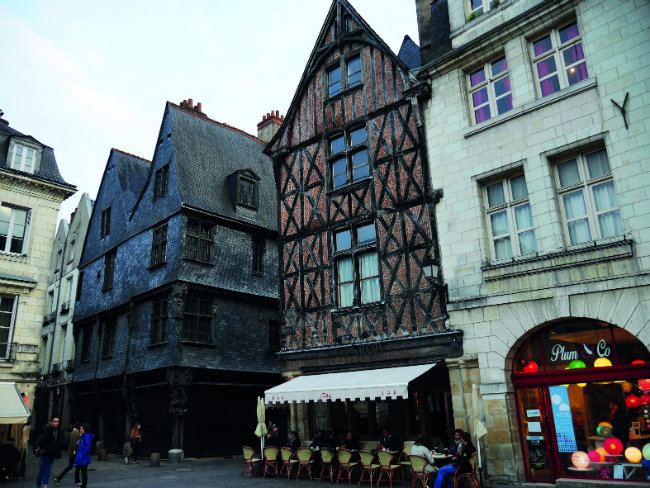

Nowhere in the Loire is this push towards the arts so visible and drastic as in the city of Tours; a mercurial marvel of old and shiny new. Its tourist board’s tagline, ‘Time for Contemporary Art’, tells visitors everything they need to know. Jean Nouvel’s hulking glass convention centre, with its dramatic overhanging roof, erected directly opposite Victor Laloux’s 19th-century Baroque-inspired train station, set the modern tone in the 1990s with quite the bang. Daniel Buren (of Colonnes de Buren fame)’s trail of double-sided urban totems along the tramway line injected a decidedly futuristic edge to the cityscape in 2013; in stark contrast to Tours’s nearby old town and medieval warren of half-timbered streets. One such abode on the historic rue Colbert professes to be ‘ye olde shoppe’ where Joan of Arc purchased a suit of armour on her way to end the siege of Orléans – an unlikely tale, as said house was only built a century later. But it is the Centre de Création Contemporaine Olivier Debré, unveiled to great fanfare in March by François Hollande, which has truly upped the ante, and drawn a line in the sand for the more conservative masses. The art centre already existed. But since relaunching in its new behemoth of a home, and adopting the name of the late abstract artist Olivier Debré (whose paintings inspired by his travels to Norway are on display at the CCCOD until the end of June), it is now very much the cornerstone of Tours’s modern art triad.

The Centre de Création Contemporaine Olivier Debré (CCCOD). Photo: B Fougeirol

Made up of two ultra-modern blocks, one of them brand new, the other born out of the shell of the city’s sober, post-war School of Fine Arts, it is a sight to behold just a hop and skip from Vieux-Tours. As I join the throng of guests at the inauguration, director Alain Julien-Laferrière makes no secret of the fact the angular design ruffled some feathers. “Debré himself hated modern architecture,” he throws in casually. “He loathed harsh lines. Not that it matters,” he grins, adding that selling the concept to the late painter’s family took some convincing. His unapologetic (but glorious) all-guns-blazing tack surely sums up the region’s modernisation drive. Tearing down part of the city centre to make way for an art hub is only the tip of the iceberg. Much like at Chaumont, unexpected shoots of modernity have sprung up in the unlikeliest of places – even in the 13th-century Cathédrale Saint-Gatien. Gothic façade aside, a sombre church it is not. Craning our necks to pinpoint the source of the dazzling burst of orange light bathing the nave, we locked eyes with… a row of tents. To mark the 1,700th anniversary of the birth of Tours’s iconic saint, Martin, whose acts of charity are storied, the Church commissioned Collin-Thiébault to create a bold set of stained-glass windows. Instead of the usual Bible scene, the artist chose to immortalise a charitable campaign to provide tents to the homeless along Paris’s Canal Saint-Martin in the mid-noughties. I emerge from the darkness quite giddy, as though in on a secret.

All this tourist modernity sits alongside the “tourist brochure” Loire Valley. Photo: Marion Sauvebois

“People say the town is bipolar,” grins our guide. An improvement surely on its previous moniker, La belle endormie (sleeping beauty), she points out. Tours, like the rest of the Loire Valley, has woken up, that much is clear. Whether to a fanciful dreamland or a nightmare is the hot-button issue amongst our group. Beauty, as they say, is in the eye of the beholder.

From France Today magazine

Window in the Saint-Gatien Cathedral. Photo: Marion Sauvebois

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *