Taming the Beast: Mont Ventoux and the Tour de France 2021

Champion cyclists have lost their lives battling ‘The Beast’ Mont Ventoux and yet this year’s Tour de France challenges riders to make the ascent twice in one day. Steve Wartenberg reports.

The 103rd Tour de France will feature something new and even more dastardly for the cyclists: not one, but two climbs to the summit of legendary Mont Ventoux. In one day. Maybe.

The route of the Tour is different every year, and the last time it visited the Ventoux was 2016. The Mistral was in full force that day, especially angry, with 125km gusts of wind pummelling the treeless, rocky peak. This made it too treacherous for the riders – the greatest bike handlers in the world – to race to the summit. They would have been tossed about like kites in a hurricane. Instead, the stage ended at Chalet Reynard, the café that’s 6km from the 1,910m summit, and a couple of kilometres below the memorial to Tom Simpson, the British rider who collapsed and died here during the 1967 Tour.

© ALAIN HOCQUEL

The riders didn’t seem to mind the abbreviated finish in 2016. Especially Chris Froome, the yellow-jersey leader and eventual winner. A few kilometres below Chalet Reynard, the crowds surged and closed in on the riders. Froome crashed into the back of the cyclist in front, who crashed into the back of the motorbike (carrying a cameraman) which had been forced to come to an abrupt stop by the mass of people. Froome tossed aside his broken bike and started running up the steep road until help – and a new bike – arrived. The video of the frantic cyclist running up a mountain, surrounded by thousands of screaming fans, went viral and attracted 284,000 views (and counting) on YouTube.

Cycling fans have come to expect the unexpected, the dramatic and even the tragic when it comes to Mont Ventoux. “The Ventoux is a god of evil, to which sacrifices must be made. It never forgives weakness and extracts an unfair tribute of suffering,” is the famous quote from French philosopher Roland Barthes (1915-1980), who was an avid cycling fan.

When the route for the upcoming Tour was first announced, the big news was the two ascents of Ventoux in a single day. Stage 11 promises to be the most gruelling, and quite possibly the most exciting and important day of the Tour. What would Barthes have to say about two climbs in one day? Oh, the sacrifices and suffering.

2002 tour by Christopher Voitus. © Wikimedia

TO THE MOON

The peak of the Ventoux – the Giant of Provence – is 1,909m high and is often, and aptly, described as moonlike. It’s covered with white, limestone rocks… and nothing else. The Mistral often awaits to punch cyclists in the face when they round a corner and meet it head on. Unlike the Tour climbs of the classic cols of the Alps and the Pyrenees, which are surrounded by other high peaks, the Ventoux stands alone. Towering over Provence, its white peak is visible from many miles away in every direction.

There are three routes to the top, roads from each of the base towns: Bédoin, Malaucène and Sault. The Bédoin route is considered the most difficult, the one traditionally ridden in the Tour. The Malaucène route is a little less difficult, while the Sault road is the “easy” one – until it hits Chalet Reynard and meets up with the Bédoin route for the final six kilometres.

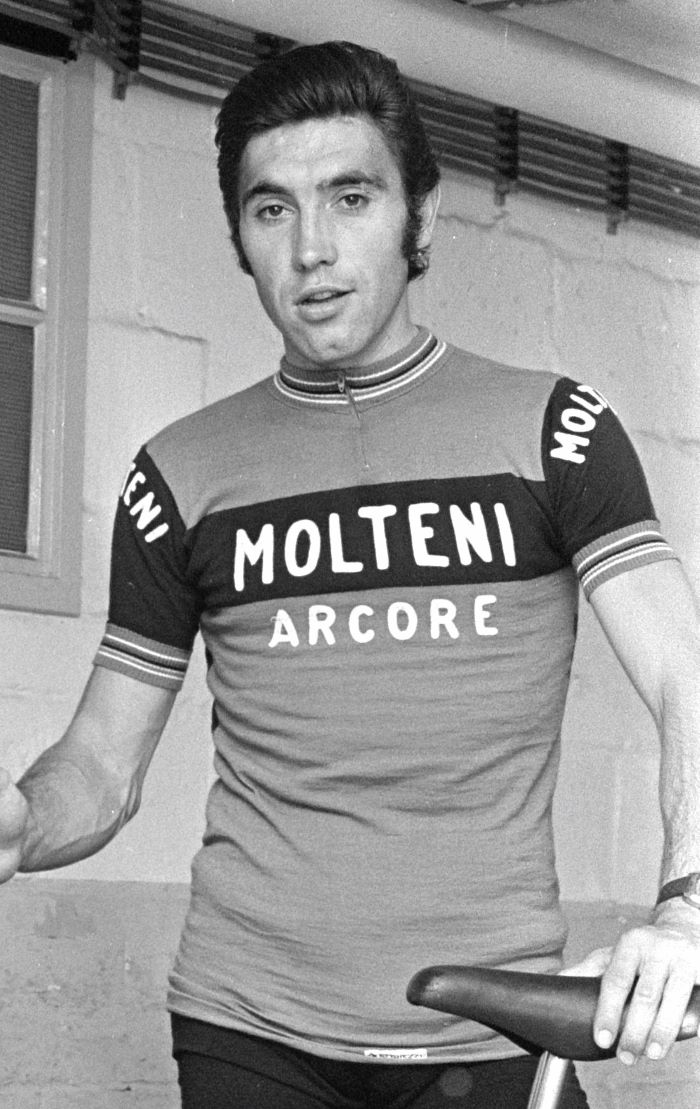

Tom Simpson, 1966.© Wikimedia/ Panini

Thousands of non-professional cyclists from around the world come to Provence every year to take on the Ventoux. If they make it to the top, they hold their bikes aloft in front of the summit sign for the mandatory photo to be shared on social media.

A PROVENCE TOUR

The 199-mile Stage 11 of the upcoming Tour starts in Sorgues, and meanders through Provence: Gordes, Roussillon, Apt and Saint-Saturnin, before the riders reach Sault and the first ascent. This would be a wonderful, two- or three-day route for a cycling holiday, filled with hilltop villages, vineyards, cherry orchards, fields of lavender and leisurely café lunches.

After the 24km climb from Sault, the riders will fly down to Malaucène, then ride around the base of the mountain to Bédoin. From here, it’s 21km back up to the summit, and then back down to Malaucène for the finish. Twice up the mountain adds up to 835m of climbing. This is the equivalent of climbing to the top of the Eiffel Tower an exhausting eight-and-a-half times. But as gruelling as the two ascents promise to be, the descents may be even more riveting to watch on television. Be prepared to cringe and gasp as the riders fly down the mountain at speeds as fast as 100kmh, wobble and skid around tight corners, coming perilously close to the edge – and disaster.

A LOT OF TOUR HISTORY

A stage of the Tour has finished atop the Ventoux 10 times, if you include 2016, the most recent summit finish (or, near-summit finish, in this case). Seven other times riders have climbed the Ventoux, and then ended the stage in a town down below.

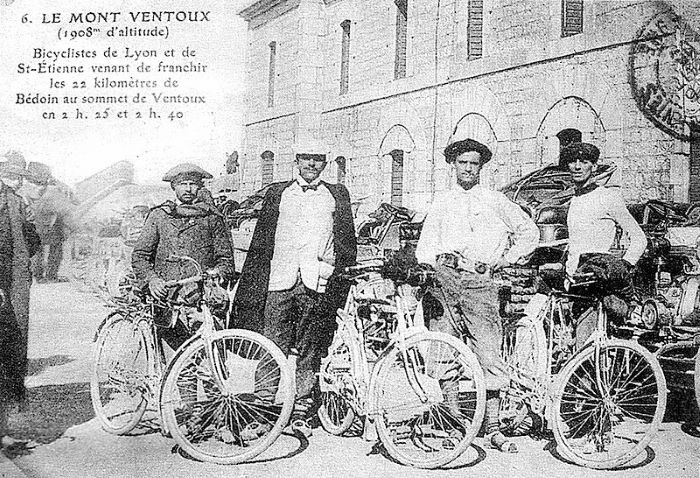

1907 amateurs Fanfarigoule. © Wikimedia

The first summit finish was in 1958, a time trial, from Bédoin. This meant the riders set off one-by-one one, a couple of minutes apart, with no teammates to help them. The nickname of Luxembourg’s Charly Gaul was ‘Angel of the Mountains’, and he certainly lived up to his moniker. Gaul won the time trial in a record-setting time of 1:02:09, a big step on the way to his one-and-only Tour victory.

THE CANNIBAL CRUMBLES

Belgium’s Eddy Merckx was known as ‘The Cannibal’, in honour of the way he devoured the competition. A five-time winner of the Tour, Merckx is considered the greatest cyclist them all. And yet, the Ventoux left the Cannibal with a bad taste in his mouth during the 1970 Tour. He attacked early on the climb, leaving his competitors far behind as he raced up the mountain, seemingly invincible, immune to the sacrifices. And then, the god of evil exacted its toll. The mighty Merckx struggled to turn the pedals as he neared the finish, crossed the line first… and either collapsed or fainted, saying, “No, it is impossible,” according to various accounts. He was then rushed off to an ambulance and given oxygen.

PIRATE WARS

The 2000 race up the Ventoux became a two-man contest: Lance Armstrong, gunning for his second consecutive Tour victory, and Marco Pantani, the 1998 winner, nicknamed ‘The Pirate’ for his bald head and ever-present bandana. While it was later discovered both riders took illegal, performance-enhancing drugs, their battle to the peak was nevertheless legendary – and controversial. Armstrong, the yellow-jersey leader, urged Pantani, who was well behind in the overall standings, to work with him to distance themselves from the rest of the contenders to pad the American’s overall time advantage. Near the top, Armstrong eased off a bit, allowing Pantani to get the prestigious stage victory, perhaps as a thank you for working with him. Pantani resented the ‘gift’, saying he could have beaten Armstrong on his own. Armstrong said: “I also feel like it was a mistake to give the gift. He’s a great rider, a great champion and great climber, but he wasn’t the best man on Ventoux. Anybody who watched that race knows that.” Pantani later dropped out of the 2000 Tour due to illness. He died in 2004 from a drug overdose.

Eddy Merckx Molteni 1973 IMAGE © Flickr Nationaal Archief

PUT ME BACK ON MY BIKE

In March 1967, Tom Simpson, the 1965 world champion, won the Paris-Nice race. When the Tour set off at the end of June that year, he was a favourite. But a couple of kilometres past Chalet Reynard, he collapsed and fell to the side of the road. A doctor rushed to his side, but failed to revive him. According to legend, Simpson’s last words were, “Put me back on my bike”. The cause of Simpson’s death has been attributed to the excessive heat that day, combined with dehydration and his use of amphetamines.

The Tour returned to the Ventoux in 1970 and, during his breakaway stage win, Merckx threw a salute to his friend and former teammate as he rode past the memorial to Simpson, which is located close to the spot where he collapsed.

It has become a time-honoured tradition for the non-professionals who climb the Ventoux to stop, on their way up or down, at the Simpson memorial. And to leave a token – a water bottle, cycling cap, or a nearby rock – as a way to pay their respects. To the man, and to the mountain.

Tour de France at Bédoin in 2013 IMAGE © PANINI VIA Wikimedia

THE LOWDOWN TOUR BASICS

The first and most important thing you need to know about the Tour de France is: yes, it’s confusing! It’s several races within the race for the famed yellow jersey, with numerous overall and daily winners, so many strategies, ways to win, ways to lose and to crash.

Rather than trying to explain everything, a task as Herculean as climbing Mont Ventoux twice in a day, here are a few pearls to help you better understand and enjoy the 103rd edition of the world’s greatest sporting spectacle.

STAGES: There are 21 stages over 23 days from June 26 to July 18, with two rest days. Think of each stage as an individual race. Winning even one stage is a career highlight for many riders. That’s why so many cry tears of joy as they cross the finish line – unless they’re too dehydrated to produce tears.

DISTANCE: A total of 3,383 kilometres (2,102 miles) this year.

YELLOW JERSEY: The rider wearing the iconic yellow jersey is the one who has completed the cumulative number of stages in the least amount of time.

FAVOURITES: It could be a duel between 2020 winner Tadej Pogacar and runner-up Primoz Roglic, the current world’s number-one ranked rider. Past winners Egan Bernal (2019) and Geraint Thomas (2018) could also be contenders. And then there’s Chris Froome, the four-time winner (2013, 2016-18), trying to make a comeback after two injury-plagued years.

GREEN JERSEY: The rider who has accumulated the most sprint points. Must have humongous thighs.

POLKA-DOT JERSEY: The rider with the most climbing points. Must be extremely thin and enjoy suffering.

WHITE JERSEY: The under-26 rider with the best cumulative time.

TEAMS: 23 teams of nine riders, a total of 207 riders. At the start. By the end, far fewer.

PELOTON: The name for the pack of riders, bunched together, seemingly so close their wheels will touch at any instant. Riding together reduces the wind resistance and makes cycling at 40kmh or 50kmh a lot easier.

DOMESTIQUE: A rider whose job is to help the team’s best overall rider, sprinter or climber win a stage or compete for one of the ‘colourful’ jerseys.

WHEN IN DOUBT: Sit back and take in the scenery that rolls by. The Tour de France is a three-week advertisement for the breathtaking beauty of France.

From France Today magazine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in cycling, le tour de france, Provence, Tour de France, Ventoux

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *