Sèvres: Making the World’s Finest Porcelain Since 1740

A recent exhibition at the Cité de la Céramique, the home of the Manufacture National de Sèvres and a Ceramics Museum, included a continuous video loop of the sculptor Valérie Delarue, in the throes of creation, flinging her naked body against a mound of clay. Even as part of a riveting show detailing the work of two contemporary porcelain artists, this no doubt raised some eyebrows among those visitors who were expecting something more along the lines of the classical figurines and exquisitely decorated vases and tea sets which are also impressively displayed therein. However, this juxtaposition of the contemporary and the classical speaks volumes about the Sèvres of today.

The beauty and perfection of Sèvres’ output has been celebrated throughout more than 250 years of continuous production, but raising eyebrows is a relatively new thing for the legendary Manufacture. One of France’s great cultural treasures and state-owned, Sèvres is distinct from every other producer of fine porcelain as it has the dual mission of maintaining and preserving historic techniques while remaining relevant in the contemporary decorative arts and, increasingly, also the fine arts. Thankfully, Sèvres has endured through some gravely uncertain times and is more than up to the task.

Sèvres started out as the Manufacture de Vincennes, a private enterprise established in 1740 at the Château de Vincennes on the eastern edge of Paris. Despite constant financial troubles, the factory proved innovative from the start, producing a creamy white porcelain and the first of its celebrated shades of turquoise – ‘bleu céleste’ – and a deep ‘royal blue’ which would become Sèvres’ hallmarks.

Louis XV, the reigning monarch, may have appreciated porcelain, but his illustrious mistress, Madame de Pompadour, simply adored it. Both saw the economic sense in supporting a factory which made a product that was so popular among the rich. Though several other small porcelain manufacturers with aristocratic backing existed around Paris at the time – notably Saint-Cloud and Chantilly – the King, at Madame de Pompadour’s urging, offered his royal patronage to Vincennes.

Louis XV then began setting limits on what other producers could and couldn’t do – gilding, for instance, was strictly reserved for the Manufacture de Vincennes. Meanwhile, Madame de Pompadour began to stuff her château with pieces of sublime elegance produced there, particularly the factory’s delicate porcelain flowers.

‘White Gold’

All of the porcelain makers at the time, including Vincennes, were producing soft-paste porcelain. As beautiful as it was, this could match neither the durability – it was easily scratched by a knife or fork – nor the exquisite transparency of Chinese hard-paste porcelain, which was the absolute ‘gold standard’ for ceramic ware.

Obtaining the secret recipe for Chinese hard-paste porcelain was one of Europe’s great 17th-century quests. No-one had been able to replicate the supremely refined, bright-white ceramic perfected by the Chinese over many centuries, until an alchemist employed by Meissen, near Dresden, came up with a recipe which was based on information – smuggled out of China by Jesuit priests – that named kaolin as the magic ingredient. Once Meissen began, very lucratively, exporting their ‘white gold’ throughout Europe, the race was on.

At the time, the power and influence of France was such that Louis XV did not easily countenance being outdone. He’d already thrown his royal wealth and influence behind Vincennes, attracting the very best craftsmen, painters and gilders, and in 1756 ordered that the whole operation be moved to new, larger premises in Sèvres, to the west of Paris, not far from Madame de Pompadour’s château.

In 1759 the King bought the factory outright, becoming sole owner, and his investment paid off. By the 1770s, Sèvres’ reputation and influence were such that monarchs and aristocrats looked to the Manufacture for the finest in porcelain services and decorative pieces. According to Hervé de la Verrie, the Director of European Ceramics and Glass at Christie’s Paris, Louis XV – and Louis XVI after him – nurtured the factory’s influence by holding exclusive showings for the ladies at Versailles, “to introduce the new shapes, patterns and colours, and made a policy of bestowing a complete dinner service on every official royal visitor – a ‘diplomatic gift’ to ensure that Sèvres was admired in the royal courts of Europe and beyond.”

In 1768, kaolin deposits were discovered outside the town of Limoges in central France and Sèvres began experimenting with hard-paste porcelain, eventually surmounting the technical hurdles posed by the clay, particularly the high temperatures required for firing and glazing. The Manufacture continued to produce both hard- and soft-paste porcelain – most notably a superb dinner service in the latter which was commissioned by Catherine the Great in 1776. This was Sèvres’ first neoclassical design, in entirely new shapes and ground colours, which was matched with the Manufacture’s trademark ethereal bleu céleste, and lavishly decorated with cameos copied from Catherine’s famous collection.

This gilded service is still considered a factory benchmark, “the most lavish, expensive and difficult ever to be produced at Sèvres”, according to Bertrand Vignaud of Christie’s Monaco. Indeed, a cup and saucer from the set fetched $50,000 at a Christie’s New York auction in 2012. By this time, emphasises Hervé de la Verrie of Christie’s Paris, “Sèvres was no longer copying Meissen – Meissen was copying Sèvres.”

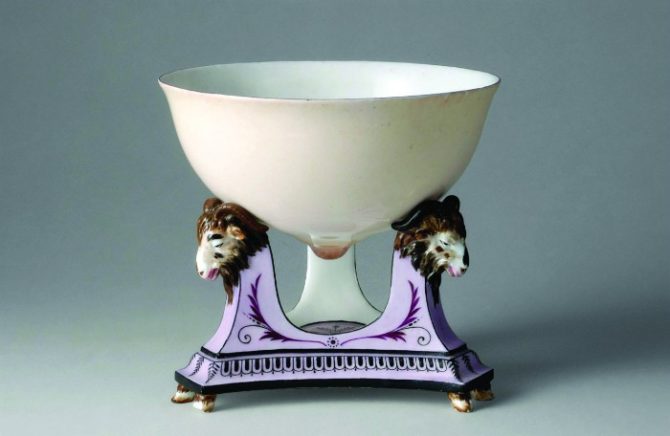

Despite the factory’s immense fame and influence, by the 1780s Sèvres was experiencing a series of minor crises, including the rumblings of the French Revolution. By the time that Marie Antoinette – whose breast was immortalised in Sèvres’ weirdly wonderful ‘Bol Sein’ milk bowl of 1787 –was carted off to the Conciergerie, the factory had racked up enough debt that unpaid workers caused a near insurrection. Paradoxically, though the Revolution posed a profound threat to the factory, via the obvious loss of its clientele, it also seeded the conditions that ensured its survival. In the 1790s Sèvres became the property of the state and somehow managed to prevail, despite France’s disastrous economy.

In 1800, the appointment of Alexander Brongniart as the factory administrator – which coincided with the reign of Napoléon – ushered in a halcyon chapter in Sèvres’ history, one which saw five decades of innovation and prosperity that laid the groundwork for the modern Manufacture. Soft-paste porcelain was almost immediately abandoned and the recipe for hard-paste improved. More effective kilns were introduced – some are still in use today – and scores of new shapes, patterns and colours were developed year after year.

Sèvres continued to appeal to the tastes of rulers – the mean cost of a vase easily exceeded the yearly wages of the average worker – and Napoléon was no exception. His hugely popular campaign in Egypt sparked a new vogue in Paris and Bonaparte himself ordered four of Sèvres’ Egyptian-inspired services, including one for Tsar Alexander of Russia and another for Joséphine at the Tuileries Palace. This service’s spectacular sugar bowl – in Sèvres blue with the factory’s virtuoso gilding – is still in production and can be purchased at the Manufacture’s boutiques.

Curation & Innovation

Alexander Brongniart also oversaw the creation of the Musée Ceramique, which was inaugurated in 1824. He assembled the world’s greatest collection of ceramics, from prehistory to the present, and this now forms an integral part of the Cité de la Céramique.

Sèvres continued innovating into the 19th century, creating a new recipe for hard-paste porcelain – there are four, one for each century of the factory’s history – and collaborating with the likes of the sculptor Carrier-Belleuse and his one-time assistant, Auguste Rodin. At the tail end of the century, Art Nouveau effectively closed the book on Classicism, ushering in Modernism with its more naturalistic and relaxed style, one which made room for flowing forms, asymmetric designs, matte glazes and a constant spirit of experimentation.

Sèvres’ collaborations continued through the 20th century, with such far-flung artists, architects, sculptors and designers as Jean Arp, Alexander Calder, Serge Poliakoff, Ettore Sottsass, Jim Dine, Pierre Alechinsky, Charles Simmonds, Betty Woodman and Adrian Saxe. Though much of Sèvres’ output, even with these artists, was still centred around tableware and decorative items, near the end of the 20th century, a subtle shift toward purely conceptual works crept in. This evolution, which coincided with the 2003 appointment of David Caméo as head of the Manufacture, was embraced and encouraged at Sèvres.

Like Brongniart at the beginning of the 19th century, Caméo’s vision both embraced Sèvres’ mandate to transmit its precious expertise in the production and conservation of fine porcelain, while also buttressing the vital connection between the Manufacture’s commercial and creative dimensions, which dated back to its inception.

“When François Boucher fulfilled the royal orders, he was seen as the Jeff Koons of his day,” Caméo says. “The goal at that time was already to produce and sell, and involve the best contemporary artists. Essentially, we haven’t invented anything since 1740!”

In 2010, Caméo oversaw the re-merging of the Sèvres’ ateliers and the museum, which had been separate since 1930, to create the Cité de la Céramique and pave the way for a new era. Inviting artists to work in the Sèvres ateliers, or accepting the advances of those who are eager to collaborate, fuels the painstaking but rewarding process of combining savoir-faire with vision and takes the art to new heights. The results can be exhilarating. Works such as Louise Bourgeois’s Nature Study (1986), gilded in pure 24-carat gold, is now a signature Sèvres piece, one that opened the door to a new generation of sculpture, experimental works and artistic collaborations, sometimes with galleries.

Sèvres now employs 120 ceramicists who perform 30 specific tasks – from throwing and modelling to painting and gilding – to produce about 3,000 pieces per year. That figure includes special orders of any of Sèvres’ historic output, which are made from the original moulds and informed by meticulous archival records. The famous artist-in-residence programme offers on-site studios to between three and ten ceramicists or fine artists per year.

Sèvres on Show

The Ceramics Museum hosts important exhibitions of contemporary artists working in porcelain – some in residence, many not – plus acclaimed shows with a historic theme, such as the recent Corée Mania exhibit, featuring the ceramic arts of Korea from the first century to the present.

The Cité de la Céramique also mounts a lecture series, holds workshops for all ages and allows visits. Sèvres’ two impressive boutiques, in Paris and on-site, offer a range of iconic pieces from every century – including the original Bol Sein and a more modern version in pure white porcelain without the elaborate Ram’s-head stand – and modern and contemporary works by sculptors and ceramic artists.

From September 16 through to January 18, 2016, the museum will present an exhibition entitled The Manufacture of the Enlightenment: Sculpture at Sèvres from Louis XV to the Revolution, which will provide an excellent opportunity to take the short walk across the Seine to one of Paris’s abiding – and still rising – stars.

Visitor Information

Sèvres, Cité de la Céramique: 2 Place de la Manufacture, 92310 Sèvres. Metro: Line 9 to Pont de Sèvres. Open daily, 10am-7pm. Closed Tuesdays. €8 (permanent collection & temporary exhibitions). Tel: +33 1 46 29 22 05

From France Today magazine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *