Exclusive Excerpt: “Chanel, The Enigma” by Isabelle Fiemeyer

Chanel burst into fashion the way you burst into literature. She began with a stroke of genius, at Étienne Balsan’s estate in Lacroix-Saint-Ouen, when she abruptly took up the fabric like a poet embarking on poetry. Throughout her life Chanel considered herself a straightforward craftswoman, but it was like an artist that she drew her creative power and inspiration from the wounds and secrets of her childhood. She produced a total, uncompromising oeuvre, yet she modestly viewed whatever she did merely as work done as well as possible. She forged a visual idiom of pure lines and simple shapes even as she simplified colour – black, white, beige, red. Her tendency toward abstraction added meaning and mystery. She became caught up in structure, so that designing became a veritable ordeal of concentration in a quest for the essentials.

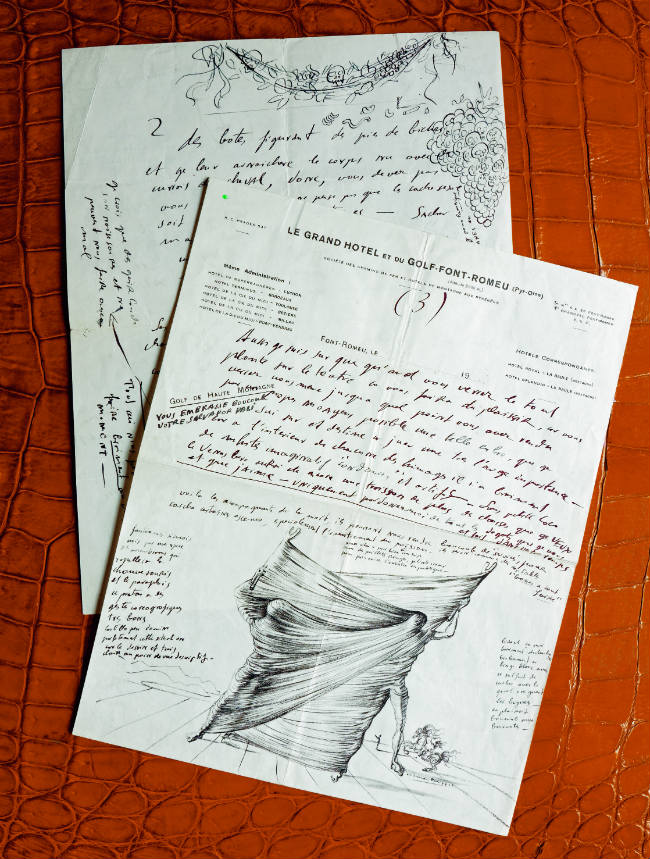

Everything began with a mental picture. Then she came up with words, giving verbal instructions to the head of the atelier. There was no drawing, no preliminary sketch. The model would stand before her like a sculpture in the making: Chanel would stitch, then unstitch, cut, trim, and slowly the line would appear, the silhouette would emerge. The novelist Colette, who knew Chanel well, described her doggedly at work, “busy sculpting a six-foot-tall angel”.

On her jewellery pouch is the necklace given to her by Paul

Iribe. © Private Collection/ Photo Francis Hammond

Everything was done in a kind of rage, or anger, which soothed her angst. Designing, for Chanel, was a pressing need: she displayed a tenacity, persistence, strict artistic orthodoxy, and drive similar to those associated with mystics. She was constructing a world as she turned out garments one after the other, like artworks, all intertwining, proliferating, cohering. Her genius was recognised at an early date, along with the startling novelty of her designs.

She scorned changes in fashion. She believed in a lasting, timeless style. She sought pure, perfect shapes that suited the body. Obeying, as always, her own inner drive, it was for herself that Chanel created garments that allowed movement. They reflected her own truth. And yet her designs were also inspired by encounters, influences, and an ongoing dialogue with artists of her day, as well as with the men she loved. During her brief affair with Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich of Russia in the early 1920s, her designs were enriched with embroidery, fur, traditional Russian motifs and Orthodox crosses. Meanwhile, her five-year relationship with the Duke of Westminster, from 1925 to 1930, a love that evolved into loyal friendship (as were all her friendships) yielded soft tweeds, cardigans, chic sweaters, sailor’s tops, and a certain idea of detachment as well as real – that is to say, non-ostentatious – luxury.

The first perfume she created, to go with her own style, was once again a question of her own intuition, of lone inspiration. She turned to Ernest Beaux, a chemist introduced to her by Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, and described the scent she had in mind. It would be a perfume that corresponded to herself, condensing yet masking all her mystery and sex appeal into a perfect, stable abstraction at a time when perfumes were merely fleeting floral scents.

She gave Beaux verbal indications – again the same process of putting a mental picture into words – and he soon returned with samples. She chose the fifth one. The name of the new perfume seemed obvious to her: just a number, 5, her lucky number. The bottle was sober, with clean lines, white label, and black lettering. Chanel No. 5, launched on May 5, 1921 was so successful that it made her wealthy and contributed to her growing legend. Unsurprisingly, the double C officially appeared for the first time on the stopper of No. 5.

iconic portrait by Man Ray– “Fashion changes, but style endures,” she used to say. Photo: Man Ray Trust

Coco Chanel’s intuitions proved accurate. She spearheaded changes in society, she incarnated modernism. The times looked to male clothing, the times favoured straight lines, fluidity, freedom, short hairstyles, suntans, and everything that Chanel had explored earlier. In 1922, the year she produced her second perfume, No. 22, her name joined those of Picasso and Honegger in the credits for a new production of Antigone by Cocteau. Other collaborative efforts followed. For example, Chanel designed the costumes for the Ballets Russes production of Le Train Bleu, working alongside Picasso, who did the stage curtain. Of such collaborations Chanel would modestly say, “I was just there for the costumes.” Consecration came in 1925, when clothing displayed at the famous Art Deco Exhibition revealed her influence. Black, her eternal favorite colour, was everywhere. Chanel, along with Reverdy, viewed black in terms of “darkness as a showcase for light”. In 1926, the year Reverdy withdrew to the Abbey of Solesmes, Chanel came up with the idea of the “little black dress,” a simple sheath of black crepe with high neck and long sleeves. It was a visionary concept that Vogue magazine called “Chanel’s Ford”.

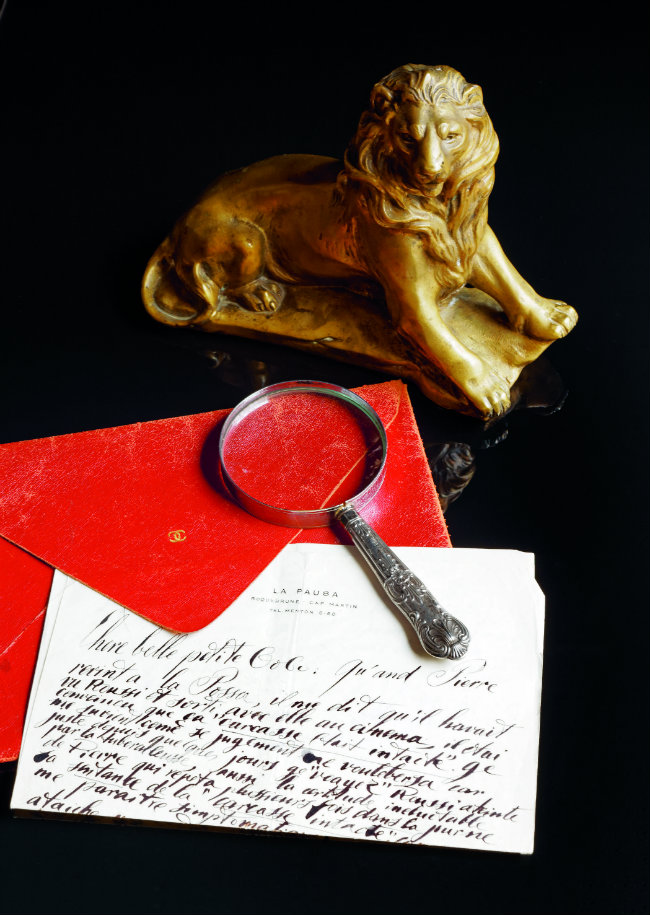

Chanel’s magnifying glass, a leather envelope, one of her

many lions, and a letter from Dalí. © Private Collection/ Photo Francis Hammond

She artfully invented locations for herself. The process of laying foundations, of sinking roots – to escape the wandering life, the family curse – was inevitably complicated. She resided, successively, on Avenue Gabriel in Paris itself, then in villas on the outskirts of town (dubbed La Milanese and Bel Respiro), then back in Paris at 29 rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré. The premises on Rue Cambon became her permanent address, established by Boy Capel – a place of work, of creativity, of life.

“When Auntie Coco said ‘my place,’ she meant Rue Cambon,” reported Gabrielle Palasse-Labrunie. Her private apartment on the third floor of 31 rue Cambon harboured an inner, private landscape full of recurring images and obsessions, of reassuring objects in a fantastic, baroque jumble that combined periods, styles, categories, and hierarchies, incarnating the pleasure of accumulating and moving. Chanel often moved things around, buying, giving away, selling off. This almost imaginary universe, which she described as “an extension of my soul,” contained her favourite symbols such as wheat, the interlaced Cs, numbers 5 and 2, symmetry, stars, lions, and her favourite colours, not to mention furniture and objects evoking important people and events in her life: a solid-wood table, statues and virgins connected with her childhood, a menagerie, mirrors, crystals, gilded wood, items connected with Venice, with the Serts, a Buddha, Coromandel screens, Oriental items associated with Boy, a painting by Dalí, a library rich in gifts of books often bearing dedications (books by her writer and poet friends, her favourite ones being marked with a simple C in pencil, plus manuscripts by Reverdy). “I make all my best trips on this couch,” she said. She travelled as little as possible, preferring the stasis of inner voyages, correspondences, and inspiring symbols.

There was also something profoundly consoling in this world of correspondences and symbols that she created around her oeuvre. Chanel always remained the little girl waiting for the love that would rescue her, ever since her father abandoned her, ever since Boy Capel died. All her life she created a waking dream for herself. When evening fell, she was afraid to “abandon herself” to the Rue Cambon premises, something nigh impossible for anyone who has been abandoned. So she preferred to sleep in a hotel, in a room tightly nestled among others, where someone would come if she were afraid. From 1936, she slept at the Ritz every night.

Coco Chanel archives. © Private Collection/ Photo Francis Hammond

Chanel’s Homes

Chanel’s locations included the Château de Corbère in the Pyrénées, where she had her own room with canopy bed and curtain – all red, obviously – and the Château de Mesnil-Guillaume in Normandy. Then there was her house in Lausanne, bought toward the end of her life but little used; and above all there was La Pausa, the only house she had built. The very idea of home had been painful since childhood, associated with marital breakdown and tragic events. As a little girl Chanel consoled herself by saying, “My father will buy me a big house.” But Albert Chanel would never show up. The “big house” would be both the “house of Chanel” on Rue Cambon and La Pausa, a villa built in 1929 on the heights of Roquebrune-Cap-Martin on the Riviera. “La Pausa was steeped in her childhood, was inspired by the architecture of Aubazine,” stated Gabrielle Palasse-Labrunie, who spent many vacations there. Everything was white or beige, with sparse furniture. There was a large, simple room, a heavy, monastic table, guest rooms of astonishing plainness, and a massive staircase recalling the one at Aubazine (correctly, in so far as architect Robert Streitz had been instructed to go look at the original). Only Chanel’s bedroom stood out, with its startling bed of Spanish brass crowned by a star.

Another iconic portrait of Chanel, by photographer Boris

Lipnitzki, 1936. © Boris Lipnitzki/Roger-Viollet

In the early 1930s, Chanel’s fame was at its height. Her business was booming, everything she touched turned to gold. In 1931 Hollywood offered her a contract of $1m per year to dress the great American stars. In 1932, in the salons of her Paris townhouse at 29 rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, she showed her first and only collection of luxury jewellery, labeled Bijoux de Diamants and orchestrated around three themes: bow, feather, and – above all – star.

Excerpted, with the publisher’s permission, from Chanel: The Enigma written by Isabelle Fiemeyer, published by Flammarion 2016.

As seen in France Today magazine. Read the France Today book review here.

one of Chanel’s favourite suits, in navy-blue-trimmed tweed with lion head buttons. © Private Collection/ Photo Francis Hammond

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *