A Provençal Christmas: The Thirteen Desserts

Whether or not several members of Christ’s inner circle drifted to the coast of Provence in an oar-less boat has never been ascertained, but some legends die harder than facts and Provençal lore likes to believe so. Not only did Mary Magdalene—who washed ashore with a handful of other exiles—spend the last years of her life on the mountain of La Sainte Baume, according to the tale, but one traditional Christmas song claims Jesus was born in Provence—Jésus Est Né en Provence—between Avignon and the town of Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, to be exact.

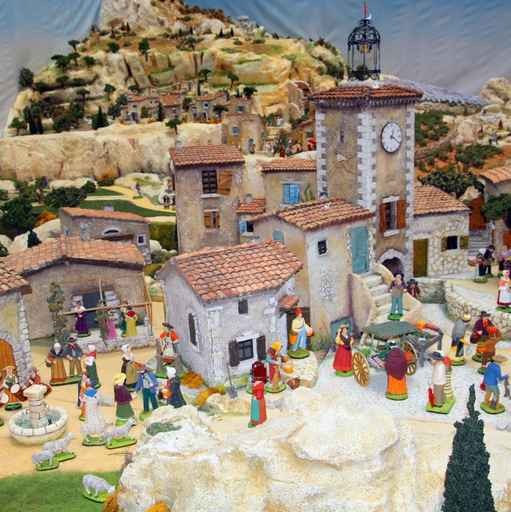

A Provençal Christmas is infused with biblical resonance, charmingly intertwined with local traditions, as exemplified by the Provençal crèche, which is populated by santons (little saints) representing not only the Magi, shepherds and angels but also butchers, bakers, farmers, fishermen, milkmaids, and dozens of other denizens of an idealized 19th-century Provençal village. Some of these traditions are surely rooted in the mists of time, but as we know them today they were introduced only after the French Revolution, part of the overall revival of Provençal culture, a cause widely promoted in the mid-19th century by Nobel Prize-winning poet and writer Frédéric Mistral. But they all convey an impression of age-old authenticity, enhanced by the rituals that punctuate the Christmas season. Known as La Calendale, the season runs from December 4th, the feast day of Saint Barbe, to February 2nd, Candlemas Day, or Chandeleur in French.

Provençal crèche, Santons

Saint Barbe (or Barbara), associated with the element of fire and the patron saint of miners and firemen, opens this month-long period of the year’s longest nights. Hence the elaborate cacho-fio ceremony for the burning of the Yule log, preferably the log of a fruit tree—almond, cherry or olive. The log is first placed on the floor in front of the fireplace, where the family gathers. The oldest member of the family conducts the proceedings, starting with a toast of mulled wine to bless the log, in the Provençal language, concluding: “If there are not more of us next year, oh Lord, may there be no fewer.” The wine is poured three times over the log, and then the oldest and the youngest of the group carry it three times around the table—or even around the house—before putting it in the fireplace to light it. Later, the ashes are gathered, to fend off illness or to be sprinkled in the fields to protect the crops.

Enchanting surprise

Earlier on the day of Saint Barbe, three little dishes might have been filled with moist absorbent cotton and planted with wheat seed, sometimes also with lentil. Their successful germination promises a good harvest and prosperity in the coming year. Once the shoots grow tall enough, they are decorated with ribbons. On Christmas Eve, the dishes are put on the Christmas table, which is covered with three white tablecloths of decreasing size, so that all three can be seen. The tablecloths and wheat shoots stay on the table until Epiphany, January 6th, along with other leafy decoration, most often holly, to bring good luck. (Never mistletoe, which brings misfortune.) Many households also add three candles or a candelabra with three branches. The recurring number three represents both the Holy Trinity and the Three Magi, and true to the spirit of early Christianity, a place at the table will be set for the pauper who may chance by.

Christmas Eve dinner is served in two stages, before and after Midnight Mass. Despite its misleading name, Le Gros Souper or Lou Gros Soupa in Provençal, which precedes Mass, is a frugal meal, in keeping with the period of abstinence that precedes the celebration of Christ’s birth. It consists of Provençal fish specialties—possibly fried cod, brandade (cod, potato and garlic purée) or a bouillabaisse—accompanied by vegetables, often seven dishes to symbolize the seven sorrows of the Virgin Mary. As the family leaves for church, the leftovers remain on the table, to feed departed ancestors.

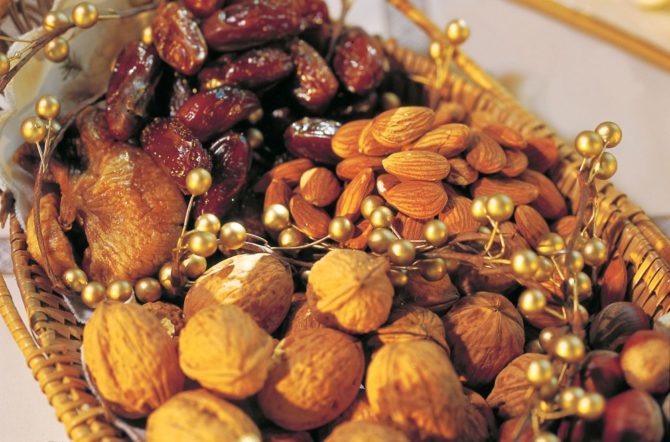

After Mass the table will be laid with les treize desserts, a colorful and festive display of thirteen desserts that’s the most popular of the Christmas celebrations. The desserts may be hidden under a white cloth, which is removed when everyone is gathered at the table, creating an enchanting element of surprise.

Figs and almonds

Figs and almonds

The tradition of thirteen desserts dates only to the end of the 19th century in Marseille, possibly originating there because the port city was the gateway to the Middle East and thus the first place to witness the arrival of such exotic fruit as dates, oranges and tangerines. Eventually those were added to local desserts, and the custom spilled over to the rest of southern France as far as Catalonia. Number thirteen was picked to represent Christ and the twelve apostles with whom he shared the Last Supper. The Christmas meal mirrors that occasion, making the story of Christ come full circle. Also in reference to Christ, it is accompanied by mulled or fortified wine, lou vin cué, which is always presented in a bottle.

The desserts must be tasted and shared by all to symbolize the act of sharing embodied by Christ, and to secure good fortune in the coming year. They will remain on the table for three days to be shared by passing guests. Some are symbolic, such as white nougat, which is made of hazelnuts, pine nuts and pistachio and symbolizes God’s virtues, and black nougat, made of honey and almonds and represents Evil. Another theory is that they represent the religious communities, the Pénitents Blancs and Pénitents Noirs. The Four Beggar desserts—dried figs, raisins, almonds and nuts—represent the four mendicant religious orders, echoing the colors of the robes of Franciscan, Dominican, Carmelite and Augustinian monks. (The robes’ colors have changed over time; the desserts have not.) Dates symbolize the arrival of Christ from the Middle East.

Although an official list of desserts was established in 1998, there are plenty of variations on the theme. Different households, towns and villages add or change them somewhat, but in essence they remain pretty much the same. Basically they fall into four categories—candied, dried and fresh fruit, and pastries. Candied fruits include the light and dark nougats, and also quince paste, sometimes candied melon and watermelon, or, in the area of Aix-en-Provence, the calisson d’Aix, made of candied fruit and ground almonds. The dried fruits are the Four Beggars (nuts fall into this category), and fresh fruits are oranges, tangerines and dates but also apples, pears, plums, grapes, Christmas melon or the lesser known, local arbutus berries.

The star of the show is a pastry, the pompe à l’huile or poumpo à l’òli, a sweet openwork bread, sometimes also called fouace or fougasse. Some claim it is as old as the city of Marseille, that is, more than 2,600 years. It must be broken, never cut with a knife, once more to commemorate the act of sharing illustrated by the Last Supper. If you can’t be in Provence for Christmas, you might be able to pick up the DVD of the film version of Marcel Pagnol’s autobiographical novel Le Château de Ma Mère, in which there is a short scene with the thirteen desserts he recalled from childhood.

Thirza Vallois is the author of Around and About Paris, Romantic Paris and Aveyron, A Bridge to French Arcadia. www.thirzavallois.com.

From the France Today archives

The Thirteen Desserts

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in christmas

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY