Fondue Savoyarde: A Recipe and History of the Alpine Delicacy

Friends, still dressed in their ski garb, gather on a restaurant terrace to skewer bread cubes onto long forks before dunking them into a bubbling cast-iron or earthenware caquelon. Steam wafts from the pot, a miniature volcano among the snow-capped summits. The image might date from an old 1950s postcard, but fast forward to the 21st century, and not much has changed slopeside. A ski vacation in the Alps still means fondue.

The wintry meal gets its name from the verb fondre, to melt. There’s no debate about that. But the argument over where fondue comes from and exactly what goes into it, however, rages up and down the mountainside.

Swiss or Savoyarde?

For most people around the world, fondue symbolizes Switzerland, ranking right up there with chocolate and precision watches. But for the French, cheese fondue is 100% Savoyarde, from France’s premier ski region. So who dipped into the gooey goodness first, the Swiss or the Savoyards? According to Isabelle Raboud Schüle, director of the Musée Gruérien in Bulle, Switzerland, fondue first delighted elite city-dwellers in places like Zurich, where the earliest known recipe appeared in 1699. “It’s hard to say exactly who invented the dish,” she cautions, “but throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, recipes for fondue were common in urban bourgeois kitchens.” Swiss kitchens, that is.

On the other side of the Alps, Thierry Thorens, gourmet writer and chef at Morzine’s La Chamade restaurant, claims that fondue resulted from the need to use leftover cheese. Alpine peasants enjoyed few luxuries and cheese was one of their more precious treasures. According to Thorens, melting several cheeses together offered a way to use leftover cheese, morsels that would have otherwise been lost. It’s important to remember that the Alps form a natural border, but man drew the Franco-Swiss frontier right through them. “Cheesemakers from Switzerland’s Gruyère region would naturally have traveled to Savoie and the French Jura,” Raboud Schüle points out. “The cheesemakers shared their savoir-faire with their neighbors, since Swiss dairy farmers had perfected hard-rind cheeses like Gruyère.”

Marketing melted cheese

Fondue may have been around in various homemade forms since the 17th century, but Switzerland and the rest of the world would have to wait for a between-the-wars surplus of cheese for the dish to climb to its iconic status. During the 1930s, Swiss farmers produced much more cheese than Swiss citizens consumed. To boost sales, the Switzerland Cheese Marketing agency needed to convince people to eat more cheese, and the more different preparations there were to tempt them the better.

In a smart move, the Union suggested four different types of fondue, each linked to a different region. A citizen of Fribourg would then be proud to serve a pot of bubbling vacherin cheese mixed with a little water. In the Valais area, a little tomato sauce added a signature rose tint. In Geneva or the Vaud region, local wines spiked local fondue. People soon latched onto their regional recipe, which joined the ranks of popular specialties.

Fondue savoyarde followed suit, using more French cheeses than Swiss. A common recipe calls for 1/3 Comté, 1/3 Beaufort—two of France’s finest mountain cheeses—and 1/3 Swiss Gruyère. Some French fondue fans may also add Abondance, a semi-hard cheese named after the Savoyarde breed of cows who supply the milk, and a town in the Haute-Savoie. But, as in Switzerland, no single recipe reigns.

From clay pot to caquelon

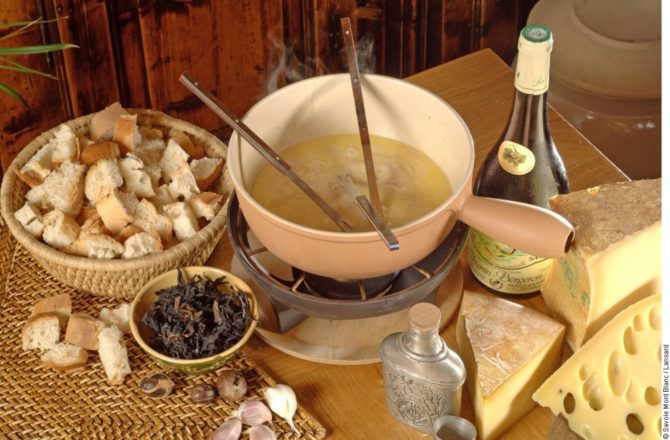

An 18th-century cook would hardly recognize a modern fondue set. Although the enameled cast iron caquelon, its convenient alcohol burner and color-coded forks made for many successful soirées in the 1970s, the earliest fondue equipment consisted of more rustic material—often just a clay pot and glowing embers. Raboud Schüle notes that “the burner-caquelon couple has only been standard household equipment since the 1950s. It wasn’t so common for earlier generations.”

After World War II, the cheese marketing agency renewed its 1930s campaign, again pushing people to ratchet up consumption of Gruyère and Vacherin. A plentiful supply after years of wartime restrictions, improvements in fondue paraphernalia and intense marketing efforts meant that Alpine society simply melted for rich, decadent fondue. What’s more, it’s a fun, easy dinner that brings friends and family together around a delicious dish. Who wouldn’t melt over that?

And what a choice of paraphernalia there is. Fondue sets have long been a popular Alpine souvenir. Some are decorated with edelweiss, others come in bold Bordeaux red or sapphire. There’s even a small heart-shaped pot for a romantic chocolate fondue dessert. While fondue apparently still has a long life ahead, it has been popular for long enough to earn its own rites and language.

Do you speak fondue?

An invitation to a fondue dinner offers the occasion to observe a number of rituals that have developed over the years. The best opportunity is when il fait un temps à fondue—it’s fondue weather. The wind chills, the clouds cloak the sun and the atmosphere absolutely calls for something hot, filling and comforting.

Once the caquelon bubbles, your host may insist on tracing figure eights in the melted cheese, supposedly the best way to prevent a solid ball from forming. “It’s more of a mnemonic device so you don’t forget to stir the mixture from time to time,” contends Raboud Schüle. “There’s no magic in the figure eight.”

While dunking, plant the bread firmly onto the fork. If it falls off in the cheese,you’re sure to get a gage—an obligation to buy a round of drinks, kiss your neighbor, or worse, run (somewhat) naked through the snow. Better be sure your bread cube can survive a fondue dunk if you want your dignity to survive a fondue dinner.

After the cheese has been swirled up forkful by forkful and finished, the pot will be crusted with toasted cheese. The near-burnt layer even has its own name—la religieuse—and this “nun” at the bottom of the pot is for some, a near-religious delight. Some say that’s where the name comes from. Others claim the vaguely Communion-wafer texture led to the name. In either case, the scraping sound at the end of the meal means that, for some, the best is yet to come.

RECIPE

La Fondue Savoyarde

If you can’t find all these cheeses, use a mixture of Emmental and Gruyère.

4 oz. shredded Beaufort cheese

4 oz. shredded Emmental cheese

4 oz. shredded Comté cheese

1 garlic clove

1 glass of white Savoie wine, such as Apremont, or any light, delicate white wine

Baguette bread cut into 1 inch cubes several hours before eating

If you’re having the fondue at night, cut the bread into cubes in the morning. This way they will have time to dry out just enough to help them stay on the forks when dipped into the melted cheese.

At serving time, cut the garlic clove in half and rub the inside of the fondue pot with it. Add the white wine and place the pot on the stove over medium heat.When the wine is hot, add the cheese by handfuls, stirring constantly. Do not add all the cheese at once. Stir the mixture until it is homogenous. Add pepper to taste and transfer the fondue pot from the stove to the burner on the table.

Each guest sticks a cube of bread on their fork and dips it into the pot, being careful not to lose the bread!

Originally published in the January 2012 issue of France Today

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *