Tiny Alabaster Giants

They are not very tall. They’ve been on a world tour for three years and are now returning home. No, it’s not a teenage pop band but a group of thirty-nine sculptures, a large segment of the complete collection of mourners housed permanently in Dijon.

A fatal feud

During the 14th and 15th centuries, the dukes of Burgundy ruled over extensive territories in present day France, Luxembourg, Belgium, and the Netherlands from their seat of power in Dijon, which meant that the city at the time was more influential than Paris. The significant artistic patronage of the dukes drew artists, musicians and writers to Dijon, turning the city into one of the main centers of artistic production in the Western world. The north of present-day France was under English occupation, and in the rest of the territory a civil war raged between Burgundians and Armagnacs, led by the Dauphin’s aspirations to control what he viewed as rightfully his. When in 1418, John the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy, captured Paris, the event brought matters to a head. After luring him into a reconciliation and swearing peace, the Dauphin (future King Charles VII) arranged a meeting to take place on the 10th of September 1419 on the bridge at Montereau. John showed up for what he thought would be a diplomatic meeting. He was, in fact, walking into an ambush and was assassinated. He was later buried in Dijon.

Art as a statement of power

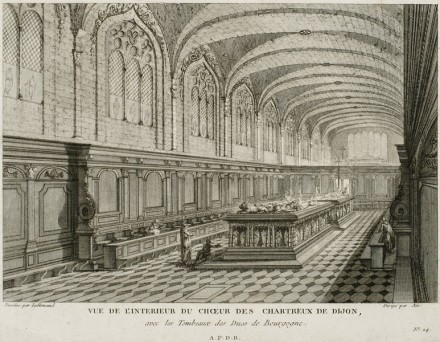

His successor, Philip the Good, commissioned a tomb in the style and scale fitting the head of state of a world power. Funerals were events of great pomp and a display of wealth not only of the deceased but also of the incumbent ruler. These affairs included processions, chanting, banners and cierges (ritual candles). Everything and everybody was draped in black. For this purpose black hooded cloaks were handed out to lay participants so that everyone would look uniformly distraught. The cenotaph features the recumbent effigies of the deceased, supported by an arcade of arches and pillars. Intertwined among these are the mourners, or pleurants, a procession of 16-inch figures expressing their sorrow or devotion to the ruler.

A triumph of sculpture

The first impression is that these cloaked images represent the clergy, but on closer inspection we can see that the artists captured all the various characters in attendance. Each one has a different expression, some are solemn, some are crying, some faces are lifted towards heaven and some are concealed inside the folds of their hood. Except for a few details such as accessories tied to a belt, a prayer book or the mitre and crozier of the bishop, for the most part there is no distinction of rank or class among the mourners. Through the use of translucent alabaster that blurs the transition between cloak and man, the effect is one of a collective snapshot of grief, but at the same time each one is a striking individual portrait of emotion.

The work was started by sculpter Claus de Werve until his death meant that Spanish artist Juan de La Huerta, a sculptor from Aragon, was given the commission provided he kept the same style and dimensions and used the same materials as in the original concept. Eventually the work passed on to French artist Antoine le Moiturier and was finally completed around 1470. The mourners are considered to be one of the most important artistic achievements of the late middle ages.

“We cannot help but be struck by the emotion they convey as they follow the funeral procession, weeping, praying, singing, lost in thought, giving vent to their grief, or consoling their neighbor. Mourning, they remind us, is a collective experience, common to all people and all moments in history,” says Sophie Jugie, Director of the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Dijon.

The exhibition

Their permanent home at the musée des beaux-arts in Dijon needed to undergo extensive renovations, and so it was that les pleurants, found themselves on a whistle-stop international tour. They visited seven museums in the USA, two in Belgium and one in Berlin, until they arrived at the final leg of the journey at musée de Cluny in Paris where the exhibition Larmes d’Albatre (alabaster tears) will remain open until June 3rd. This is an opportunity to see the mourners outside of their usual arrangement in the tomb, and appreciate them from every angle and at eye level, and see aspects that are not visible in their usual setting. After the exhibition they will return to their place in the arcade supporting the tomb of the dukes in the MBA Dijon, where they have resided for the last 200 years.

To give you a better idea of their universal appeal, here is a short video made by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) on the occasion of the exhibition of The Mourners.

Temporary exhibition:

Daily through June 3rd, 2013

Musée de Cluny – Musée national du Moyen Âge

6 place Paul Painlevé

75005 Paris

Métro Cluny-La Sorbonne / Saint-Michel / Odéon

5th arrondissement

Hours: Daily except Tuesdays from 9:15am to 5:45pm

Admission: 8 €

Telephone: 01 53 73 78 00

Permanent home:

Musée des Beaux Arts de Dijon

Palais des ducs et des Etats de Bourgogne

Open daily except Tuesday

Free admission

• With special thanks to communications office at the Musée de Cluny – Musée national du Moyen Âge

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY