Berthe Morisot and Édouard Manet: Painters in Paris

Berthe Morisot, one of the great Impressionists, was also the muse of Édouard Manet. The two may even have been in love – at least until she married his brother. Hazel Smith investigates.

At a time when women from the Parisian haute bourgeoisie were kept corseted and confined, the aspiring Impressionist painter Berthe Morisot jeopardised her ‘good girl’ reputation to model for Édouard Manet. She was evidently in love with him, and he – already infamous for exhibiting Olympia and Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, which featured the often-nude artists’ model Victorine Meurent – readily capitalised on his relationship with the young artist, capturing her in a dozen candid poses between 1868 and 1874.

Though positively demure by modern standards, Morisot’s openness was inappropriate for an upper-class Parisienne at a time when it was taboo even to venture outside unchaperoned. Morisot’s own art revealed the double standards for male and female artists. While she painted under tacit restrictions – namely that as a woman she should portray only intimate domestic scenarios – she allowed Manet to exploit her image, offsetting her own standards of decency. This made her a contradiction in Parisian art circles.

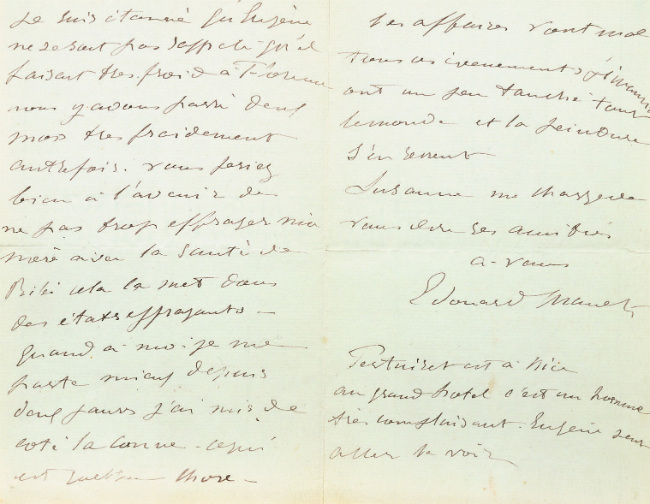

Letter from Manet to Morisot

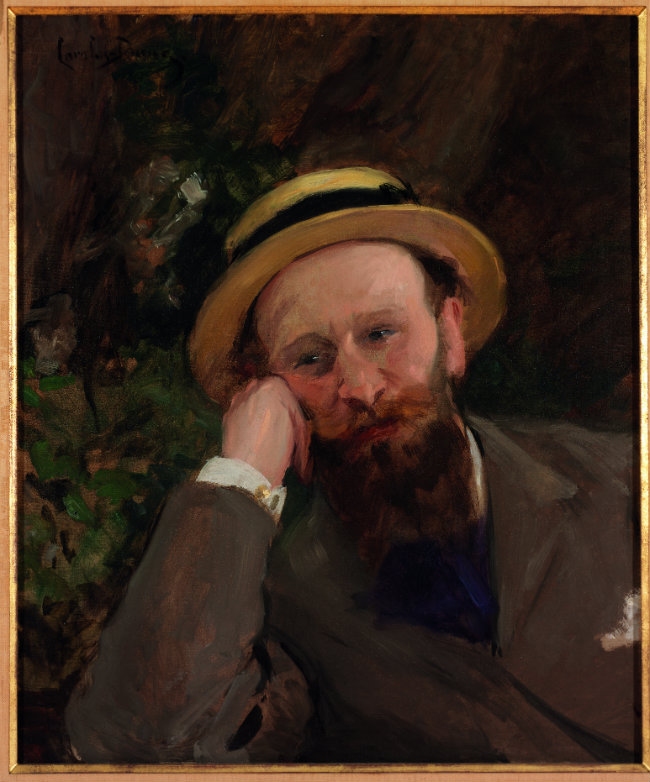

Morisot’s correspondence reveals her rather girlish infatuation with Manet. And why should she not be infatuated? Handsome and gregarious, Manet was the personification of charm. Émile Zola described him as “an elegant cavalier”, his face “at once energetic and gentle”, his eyes “of a blue as limpid as the Mediterranean in the sun”. The son of a judge, he was raised to be a gentleman in the aristocratic neighbourhood of Faubourg Saint-Germain. After becoming disenchanted by law school and proving to be a complete failure in the Navy, he trained to be an artist.

His bold streak of independence made him a natural leader. He was thought of as the godfather of the Impressionist movement, though he never allied himself with the group. A bit of a dandy, he also had a penchant for astonishing cravats. Yet he was a married man. As well as having her as a model, Manet could have seduced Morisot into being his mistress, but instead straightened his fabulous tie and found a compromise. Manet strove to ensure that Morisot kept her good name – even if that meant she should marry his brother Eugène.

Berthe Morisot in “Le Repos”, a work considered by some to be Manet’s most overt declaration of love for his muse

THE GIFT OF A PAINTING

Morisot was born into an upper middle-class family in 1841. She was indirectly related to the 18th-century painter Fragonard, renowned for his fabulously naughty The Swing (1767). The study of fine art was a major part of her upbringing. As a young girl, she and her elder sister Edma had taken lessons from their neighbour, a disciple of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, in order to present to their papa, a court official, the gift of a painting. So impressed was their instructor with the girls’ talent he recommended that they train to become professional painters – a revolutionary idea for women at the time. Morisot made her debut in the 1864 Paris Salon, and earned a regular spot for herself at the prestigious state-run show, displaying there for a decade before joining the independent group of artists that would become known as the Impressionists.

Les Lilas à Maurecourt, Berthe Morisot, 1874

In the spring of 1868 Henri Fantin-Latour, a ready fan of her dark-eyed beauty, took Manet to meet the Morisot sisters, who were busy at their easels at the Louvre. Morisot was more than happy to meet Manet; she greatly admired his work. As they walked in the same circles, the Manet and Morisot families soon formed close ties and met weekly. There developed a flirtatious dialogue between the artists, resulting in a bond that would last until the marriage of Morisot to Eugène Manet in December 1874.

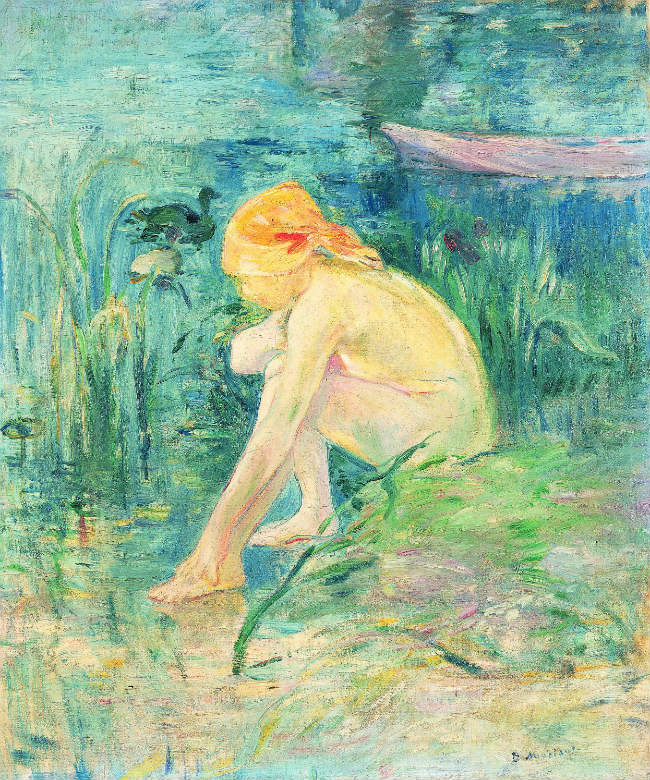

La Baigneuse, Berthe Morisot, 1891

TREMENDOUS RISK

Fantin-Latour had thought Morisot attractive, and so did Manet. By the autumn of 1868 he had convinced her to pose for The Balcony. Both must have realised the tremendous risk she was taking by posing for such a controversial artist. Morisot would be replacing the infamous Victorine Meurent, and would be open to ruinous criticism and gossip.

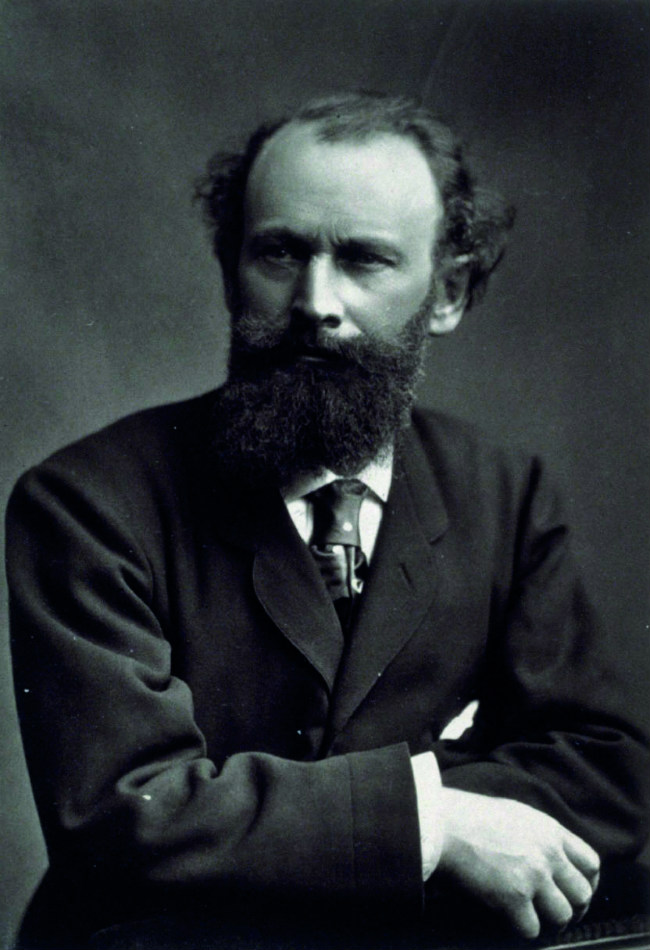

portrait of Édouard Manet by famous photographer Ferdinand Mulnier

The abuse heaped upon Meurent had been intolerable. “A female gorilla” and “a red-head of perfect ugliness” were only two of the many insults she had endured when Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe was exhibited in the Salon in 1863. The same happened when Olympia was exhibited two years later. But by 1868 Meurent had vanished and Morisot had become Manet’s favourite, going on to pose for him more than any other woman. A contemporary observed: “When [Manet] paints Victorine, he paints her as a beautiful object; when he paints Berthe, he paints her with love and tenderness.”

Photograph of Berthe Morisot

Upon the opening of the 1869 Salon, Morisot wrote to her sister Edma: “I think he has a decidedly charming temperament, I like it very much.” Her letters to Edma perhaps suggest the two were lovers, but we can only speculate as to whether their relationship became intimate, as the sisters set matches to their most revealing correspondence. It’s even more difficult to determine Manet’s attitude to Morisot. Did he return her affection?

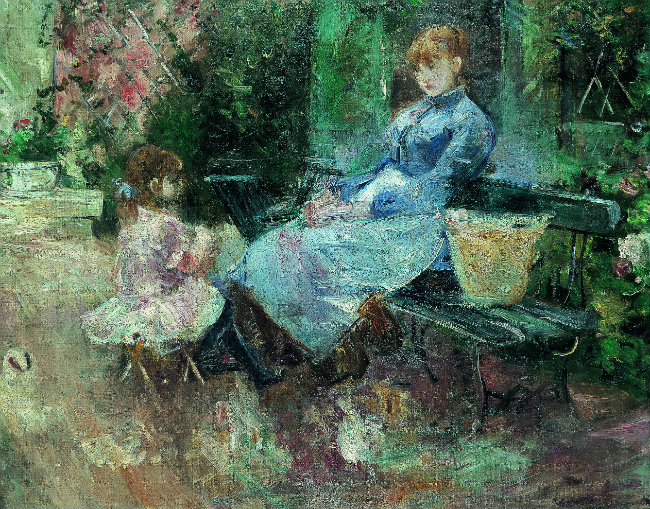

La Fable, Berthe Morisot, 1883

He thought she was pretty, and teased and provoked her as if she stirred something in him. One Christmas he presented her with a new easel. But though he praised and recommended her work to buyers, he could also be patronising. Manet wrote to Fantin-Latour on August 26, 1868: “The Misses Morisot are delightful. It’s just a pity they don’t happen to be men.” Novelist George Moore, another of Manet’s friends who also found Morisot charming, remembered Manet’s outrageous statement that: “My sister-in-law would not have existed without me.”

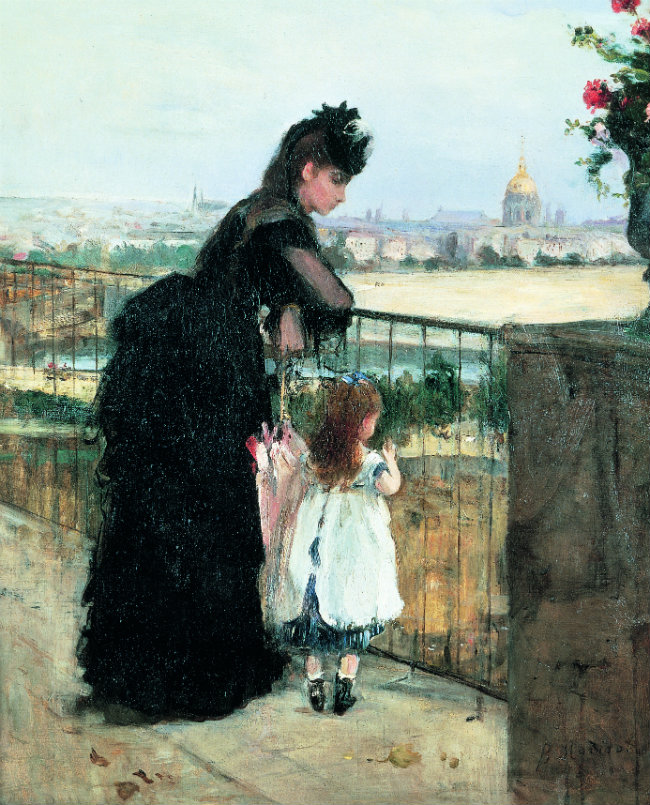

Dame et enfant sur la terrasse, Berthe Morisot, 1872

Morisot would later state: “I do not think any man would ever treat a woman as his equal, and it is all I ask, because I know my worth.” Ironically, however, it was she who persuaded Manet to paint en plein air, a departure from his usual studio work. Morisot had her own distinct style and is counted as one of the true Impressionists. Professionally, she valued Manet’s opinion, though she didn’t follow him blindly. But on a personal level, she fretted over his every gesture. Self-doubt, despondency and difficulties with eating arose from her fixation on Manet and what she called her “impossible” situation.

Portrait de Berthe Morisot et de sa fille, Berthe Morisot, 1885

And he did little to boost her confidence. Never depicting her at the bestowed easel, he portrayed her instead as a femme fatale or a grande bourgeoise. Yet Manet did paint his only paying student, Eva Gonzalès, with her brushes. Gonzalès would become Morisot’s rival for Manet’s attentions. Morisot wrote to Edma in August 1870: “Manet lectures me and holds up that eternal Mademoiselle Gonzalès as an example; she has poise, perseverance, she is able to carry an undertaking to its successful issue, whereas I am not capable of doing anything.” But by September: “Manet came to see us. To my great surprise and satisfaction, I received the highest praise; it seems that what I do is decidedly better than Eva Gonzalès.”

Morisot next modelled for Manet’s The Repose, which was exhibited in the 1873 Salon. She stepped into Victorine Meurent’s shoes as the most scorned woman at the show. Portrayed lounging on a plump sofa, with one foot dangling, the painting was denounced as a “horror”. Dubbed “Seasickness” by critics, caricaturists lampooned her casual pose. Her slouch, her exposed foot, and her open button were criticised as unattractive and unfeminine. However, essayist Otto Friedrich seemed to think that The Repose was a paean of love from Manet to his model. If it was love, Manet vicariously courted Morisot through his paintbrush, resisting real sexual tension. As the most revealing of her letters are gone, we will never know the path the relationship would trace, but George Moore confirmed in his memoirs Hail and Farewell “that Berthe would have married Manet if Manet had not been married already”.

Portrait de Berthe Morisot peignant, Edma Morisot, 1865

Morisot mutinied against her mother’s matchmaking, asserting herself as an independent, self-supporting artist. By 1872, she was over 30 years old and had rebuffed at least two suitors, one being the muralist Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. At one of Madame Morisot’s regular dinners in her Passy home, as her daughter posed for Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets, Manet addressed this issue. Morisot’s daughter, Julie Manet, confirms in her diary: “On that day Uncle Édouard told Maman she ought to marry Papa.” Was this Manet’s attempt to secure a reputable future for Morisot? Two years later, Manet’s brother Eugène revealed his feelings for Morisot. Manet approved. When she married Eugène, Morisot described her choice as a practical one; a compromise after living for years with fanciful “chimeras”. By marrying his younger brother, she bound herself to Manet with family ties and achieved the impossible: she acquired the Manet name for herself and for her child.

Portrait de Berthe Morisot à l’éventail, Édouard Manet, 1874. Image: Orsay Museum

Her marriage forced Manet to give her up as a model. She continued to paint professionally after she married, until her death at 54 years old. Manet would face her at his easel one final time after her marriage, in 1874. In the three-quarters painting, Portrait de Berthe Morisot à l’éventail, she looks aside, clutching a fan and revealing her wedding ring.

Further reading: Berthe Morisot by Jean-Dominique Rey, with a foreword by Sylvie Patry, is published by Flammarion, 2018. Purchase the book here.

From France Today magazine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

By Hazel Smith

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY

REPLY