Émile Zola’s Paris: Following in the Author’s Footsteps

Paris was a gigantic building site when Émile Zola turned 20, in 1860. “A gash… gashes everywhere, Paris slashed by a sabre, its veins slit”, he wrote a decade later in La Curée. Living through Haussmann’s metamorphosis of Paris provided obvious material for the novel that ended up expanding into his 20-volume magnum opus, the ‘Rougon-Maquart cycle’– an invaluable record as Zola was also a journalist and a passionate photographer.

Reading Zola and following him through Paris, is not unlike contemplating Charles Marville or Eugène Atget’s old photos of the city, or the paintings of his Impressionist friends. ‘Le Quartier Haussmann’ in western Paris, around the Parc Monceau especially, was tree-lined and dazzling white, as new as the money of what Zola termed its “mushroom aristocracy”. Rue de Monceau, south of the park, was lined with opulent hôtels particuliers, to which the Musée Nissim de Camondo bears witness. Monsieur Saccard resides there in La Curée, having amassed a neat fortune through speculation. His oversized dining table symbolises the main activity of the new bourgeoisie, other than fornication, which flourished on the northern side –along Rue de Prony and Rue Fortuny in particular. Zola wrote of the “very well maintained townhouses, with footman, powdered concierge, imposing staircase, huge landing, couch, armchairs, flowers”, which were the preserve of courtesans, where “semi-senile, debauched males were ready to abandon everything for an arse”.

Place Malesherbes (now Général-Catroux) was their holy of holies – witness the neo-Renaissance seat of the Banque de France (100 boulevard Malesherbes), the sole survivor of the neighbourhood’s past splendour. Inspired by the Château de Blois, it was built for the banker and art collector Émile Gaillard by the architect of the day, Jules Février. Gone are Février’s palatial homes built for society painter Ernest Meissonnier and actress Sarah Bernhardt, respectively on the corners of Rue Berger and Rue Fortuny (a hideous building has replaced the latter).

La ‘Comtesse’ & Batignolles

Gone too is the home Février built for the notorious ‘Comtesse’ Valtesse de la Bigne (the model of Zola’s and Manet’s Nana), “of Renaissance style, with the air of a palace”. Zola shifted it from 98 boulevard Malesherbes to the corner of Avenue de Villiers and Rue Cardinet. Thanks to her artist friends, Valtesse is now immortalised at the Musée d’Orsay and elsewhere, yet she denied them access to her boudoir.

“It is not within your means, mon cher maître”, she said to Alexandre Dumas fils, making an exception for Zola on professional grounds. Her bed and altar, which he described in Nana, is on display at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, by the Louvre. The statues of Alexandre Dumas, père et fils, and of Sarah Bernhardt as Phèdre, grace the leafy Place du Général-Catroux, as reminders of an ephemeral time when money and thinly disguised prostitution mingled happily with the upper echelon of the artistic community.

The other artists settled for the humbler Batignolles, further north, the birthplace of the Impressionist school, then known as ‘le groupe des Batignolles’. Zola, who lived at 23 rue Truffaut and at 14 rue La Condamine, respectively, in 1868 and 1869, appears among them in Fantin-Latour’s painting, Un Atelier aux Batignolles. He also joined them with Manet at Café Guerbois, at No. 9 grande rue des Batignolles (now Avenue de Clichy), next to Hennequin’s paint shop, Manet’s supplier – at No. 11. In return for his unflinching support, Manet painted his portrait, which now hangs at the Musée d’Orsay.

Cézanne, on the other hand, never forgave Zola for his portrayal of Claude Lantier in L’Oeuvre – largely inspired by his person, but also by Monet and Manet, who took no offence. The Avenue de Clichy is now heavily ethnic. Few notice the old mosaic decoration above the sports shop at No. 11, featuring an artist’s palette and paint brushes. Head instead to La Bonne Franquette in Montmartre, where they also gathered, as featured in Van Gogh’s well-known La Guinguette.

Batignolles proper has kept a village atmosphere, a laid-back mix of young families and old-time retirees. The English-style Square des Batignolles, dating from Haussmann, was not to Zola’s taste (unlike Parc Monceau), who wrote in Le Figaro in 1867 that “it had the picturesque aspect of gardens that retired grocers plant around their villas”. Running along the gardens, coming from Gare Saint-Lazare, the ‘Western Railway’ was a welcome novelty, celebrated by Manet, Caillebotte and Monet, featured by Zola in La Bête Humaine, a thriller played out along the Paris–Le Havre line. The old rail fallows have been replaced by a new development and a vast park commemorating Martin Luther King Jr. By 2017, architect Renzo Piano’s Court of Justice will tower 160m above them, on their north side.

Black Smoke & Lost Lifeblood

La Goutte d’Or (Métro: La Chapelle), is a short ride from Monceau, yet light years away. It was a Dickensian neighbourhood of decrepit hovels, factories and railways, reeking with poisonous black smoke, when Zola wrote L’Assommoir: “The chests were hollow merely from inhaling this air, where even gnats could not live for lack of food.”

Absinthe seemed the only escape, as recorded in Degas’ painting Au Café (l’Absinthe), which inspired Zola “to paint the fatal degeneration of a working-class family in the foul environments of our faubourgs [suburbs]”, eventually forcing the heroine Gervaise (Nana’s mother) into prostitution. La Goutte d’Or is now a tiny patch of Africa, to be explored (with caution) before regeneration washes out its local colour. The brick wash-house on Rue des Islettes where the laundresses gathered, gossiped and bickered has long since disappeared. Only the adjacent Place de l’Assommoir bears witness to the novel that made Zola’s fame and fortune.

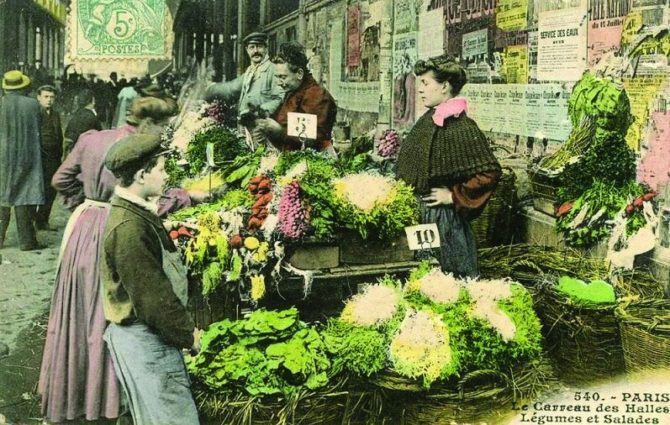

The unforgivable demolition of the old Les Halles market in 1971 set Paris mourning. Its current makeover, the second since 1977, cannot repair the damage. Old photos bring alive the lost lifeblood of Paris, as does Zola in Le Ventre de Paris– the ceaseless nightly commotion as the bounty of France kept pouring in. The mountains of vegetables, the sea of bouquets of laurel and thyme at the foot of the church of Saint Eustache, and the fleeting play of light on Baltard’s steel-and-glass pavilions – all demolished but one, irrationally exiled to the eastern suburb of Nogent-sur-Marne. Those nostalgic for Zola’s time will find comfort in the tiny bistro Le Cochon à l’Oreille, complete with its exquisite period interior, decorated with scenes of the old market.

Speculation and commerce advanced hand-in-hand in Haussmann’s Paris. The men’s place of worship was the stock exchange (La Bourse), their fate determined by “the mysterious turn of the wheel of fortune”. The women worshipped at the “modern bazaars”, succumbing irresistibly to the lure of advertising. Au Bon Marché, founded in 1852 by Aristide Boucicaut (Octave Mouret in Zola’s novels), and the defunct Grand Magasin du Louvre (opposite the Louvre), served as models for Zola’s Au Bonheur des Dames. Entirely revamped since his days, and stripped of Gustave Eiffel’s spectacular ironwork, today it is the food hall, la Grande Épicerie, which lures shoppers to the Bon Marché.

Life and Death

Zola’s Paris is also his own life story – starting off in wretched lodgings in the Latin Quarter early on, attending the glamorous opening of the Garnier Opera House in 1875, “dripping with diamonds”, commenting on “the staggering luxury that flaunted itself in all the boxes”.

Attending a Rothschilds’ wedding the following year, he was satisfied that the age-old hatred of the Jews was over: “Time has marched on, civilisation and justice have gained ground”. Less than 20 years later, his illusions would be shattered, when the Jewish Captain Dreyfus would be framed and wrongly accused of treason. On January 13, 1898 Zola’s manifesto in defence of Dreyfus, addressed to the President of the Republic, Félix Faure, covered the front page of L’Aurore under the title J’ACCUSE!, making history. Financial ruin, a jail sentence and hefty fine, exile to England to avoid incarceration and hundreds of death threats were the price Zola paid for fighting for justice: “Truth is marching on and nothing will stop it”.

A plaque commemorates Zola’s manifesto at No. 140-144 rue Montmartre, where L’Aurore was located, opposite L’Humanité across the street. This was the heartland of the press where Zola was born, in 1840, at 10 rue Saint-Joseph. On July 31, 1914, Jean Jaurès, the editor-in-chief of L’Humanité, was assassinated for his pacifist views at La Chope (now La Taverne) du Croissant, on the nearby corner of Rue du Croissant. The culprit, an anti-German nationalist, Raoul Villain, was acquitted.

In all probability, Zola was also murdered by anti-German – and anti-Jewish – nationalists. On the morning of September 2, 1902, he and his wife Alexandrine (who survived) were found suffocated by obstruction of the chimney in their home at 21 rue de Bruxelles. On June 4, 1908, Zola’s ashes were transferred to the Panthéon, the shrine of the nation’s heroes, amidst howls of “Spit on Zola! Death to Zola!” Alfred Dreyfus, who attended the ceremony, was shot in the arm during an attempt on his life. The culprit, Louis Grégori, was acquitted.

Zola’s Paris Essentials

Want to follow in the footsteps of the iconic novelist? Here’s what you need to know…

Musée des Arts Décoratifs: 107 rue de Rivoli, 75001, Paris. Open Wednesday to Sunday (Thursday until 9pm for temporary exhibitions). Closed December 25, January 1 & May 1. Tel: + 33 1 44 55 57 50

Musée Nissim de Camondo, 63 rue de Monceau, 75008 Paris. Open Wednesday to Sunday, 10am-7.30pm. Closed December 25, January 1 & May 1. Tel: + 33 1 53 89 06 50 / 53 89 06 40

A La Bonne Franquette, 2 rue des Saules / 18 rue St Rustique, 75018 Paris. Open daily. Tel: +33 1 42 52 02 42

Le Cochon à l’Oreille, 15 rue Montmartre, 75001 Paris. Open Tuesday to Saturday until 5pm. Tel: +33 1 42 36 07 56

La Taverne du Croissant, 146 rue Montmartre, 75002 Paris. Open Monday to Saturday. Tel: +33 1 42 36 07 56

Thirza Vallois is the author of Around and About Paris, Romantic Paris and Aveyron, A Bridge to French Arcadia.

From France Today magazine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY