French Icons: The World’s First Illustrated Posters

De placards délicieux,

D’affiches multicolores…

Raoul Ponchon, Mâitre Chéret, 1890

During the final decade of the 19th century, Paris was seen as the artistic and entertainment capital of the world, and this was reflected in the gaily-coloured posters which adorned the city’s walls and kiosks. Advertising the growing number of Parisian dance halls, cabarets and café-concerts, the illustrated poster or affiche illustrée became synonymous with Parisian nightlife. This visual revolution, which was to have such an enduring effect on Parisian society, was largely pioneered by one man, the artist and lithographer Jules Chéret.

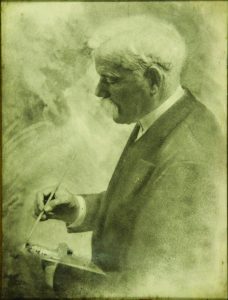

Jules Chéret / © musée des Beaux-arts Jules Chéret

For much of the first half of the 19th century, posters were primarily printed using the letterpress method – made up with typefaces of varying sizes, with little or no design aesthetic involved. Chéret was to change the concept of the poster by including colourful illustrations, combined with decorative, hand-drawn lettering, an approach which was made possible by the burgeoning lithographic printing process. Although lithography was invented at the end of the 18th century, artists were surprisingly slow to appreciate the benefits that the method brought to the printing industry.

However, in 1866 Chéret produced what’s generally accepted as the first illustrated poster. At a later date he set up his own printing business and an artists’ studio specialising in poster production. After much experimentation, he created a technique and style that became a template for other poster artists to aspire to.

The Poster King

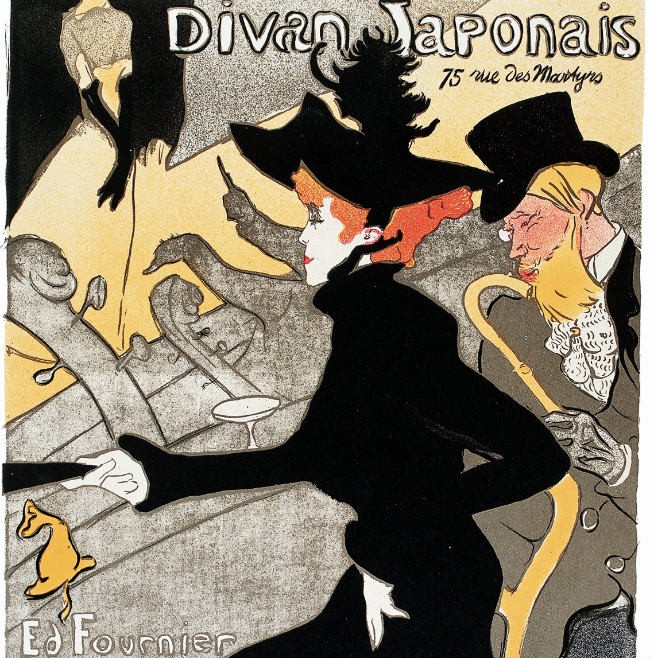

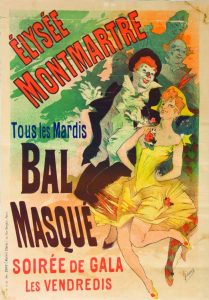

Jules Chéret, Élysée Montmartre. Tous Les Mardis Bal Masque, 1891 / © musée des Beaux-arts Jules Chéret

The illustrated poster came of age in 1889, at the Exposition Universelle, an international exhibition in Paris that was mounted to mark the 100th anniversary of the storming of the Bastille, where Chéret was awarded a gold medal for his contribution to art and industry. Critics of the time hailed him as the ‘father of the pictorial poster’, ‘the poster king’, and ‘the Watteau of the streets’ – the latter alluding to the influence of the French, 18th-century Rococo artist Jean-Antoine Watteau upon his work.

Thanks to Chéret, a new industry had been established. His work was to have a profound influence on many artists of the time, including Edgar Degas and Georges Seurat, and inspired Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Pierre Bonnard to engage in poster art. In themselves, posters became objects of desire, with print dealers including them in their catalogues.

New galleries, such as the Salon des Cent, were established to further promote poster artists and their works, and specialist collector magazines were published. Posters were also used to advertise a wide variety of commodities that catered to the needs of the flourishing consumer market.

A Significant Oeuvre

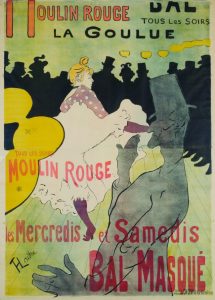

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Moulin-Rouge. La Goulue, 1891 / Musée Toulouse-Lautrec

Chéret’s own output was vast. During the last quarter of the 19th century, he produced over a thousand posters, many of them for Parisian dance halls, ‘café-concerts’ and theatres, including some 65 for the Folies-Bergère music hall alone. Typical of his oeuvre is an 1891 poster for the Élysée Montmartre dance hall, which features a provocatively dressed female dancer in the foreground, surrounded by Pierrot and clown figures.

Producing a colour lithographic poster was a complicated process. In the first instance an original design was produced by an artist – in this case, Chéret himself. Then, at the Chaix Imprimerie works, to whom Chéret sold his printing business in 1881, each designated colour was drawn – in reverse – onto a litho stone. This involved a variety of specialist tools and materials, such as waxy crayons and lithographic drawing ink. Chéret’s mastery of the lithographic printing process is demonstrated in the way he achieves a vibrant overall effect using the minimum of colours.

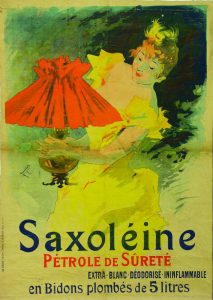

Jules Chéret, Saxoléine, 1896 / © musée des Beaux-arts Jules Chéret

Chéret produced his best works during the last decade of the 19th century. Aside from the large quantities of posters he designed for the Parisian entertainment industry, Chéret also advertised a great many commercial products. His posters of this period exude an air of gaiety that’s exemplified by the appearance of glamorous female models, commonly known as les Chérettes. Whatever the product in question, the female Chérette character, for whom he often used his wife as a model, was employed as the main feature in order to entice the customer.

Alcoholic beverages of all kinds were commonly promoted using affiches illustrées. Chéret produced posters advertising Vin Mariani, a popular tonic wine, and, most famously, the aperitif Quinquina Dubonnet. In the Dubonnet poster, the female character depicted by Chéret is the popular actress and singer Lise Fleuron (real name Marguerite Rauscher), who appears almost intoxicated by the aperitif.

a hand-coloured lithograph of Aristide Bruant’s cabaret, Le Mirliton, circa 1894 / Graham Twemlow Collection

Chéret had the ability to make even the most mundane of commodities look exciting. His series of posters for Saxoléine, an unscented paraffin product for oil lamps, are arguably the most successful of his output. Again, the Chérette depicted in the poster is probably modelled on his wife, and she’s brightly illuminated by the lamp that she’s lighting, perhaps having just returned from an evening’s entertainment. Chéret succeeds in giving the public a beautifully illustrated poster of a chic woman in a low-cut yellow evening dress, while ensuring that the commercial, least glamorous aspect of the poster – lamp oil – is clearly featured.

What isn’t always clear from the reproductions of affiches illustrées is the fact that many of them were extremely large, as is the case of the Saxoléine poster, which comprised of two separately printed sheets.

Montmartre Nights

Jules Chéret, Saxoléine, 1896 / © musée des Beaux-arts Jules Chéret

Although they were accepted by many critics and print dealers, others were sceptical about the merits of the illustrated poster as an art form. Serious artists shunned the medium but attitudes were changed when, in 1891, the Montmartre-based Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was commissioned to design a poster for the Moulin Rouge dance hall.

First opened in 1889, the Bal du Moulin Rouge became a great success, partly because of its location on an outer boulevard of Montmartre – away from the seedier side of the district. It consisted of a dance floor, a wide upper gallery, a stage for café-concerts and an ornamental garden with bizarre attractions. Performers such as La Goulue, Môme Fromage and Yvette Guilbert helped put the establishment at the forefront of Parisian entertainment.

However, by 1891, business was beginning to wane and the owners of the Moulin Rouge entrusted Toulouse-Lautrec with the job of winning back customers by producing a poster like no other affiche of the time.

Toulouse-Lautrec made Louise Weber, who was known professionally as ‘La Goulue’ (the glutton), the focal point of his seminal composition. She’s depicted in what was known as ‘the guitar’ stance, which is associated with ‘le quadrille naturaliste’, a popular and provocative dance of the time which was later known as the can-can. Her partner, who takes up much of the illustration’s foreground, is Parisian wine merchant Jacques Renaudin, who was otherwise known as Valentin le Désossé (the surname meaning ‘boneless’) and regularly joined La Goulue for her exotic dance routines.

a postcard of the Moulin Rouge circa 1900

Prior to 1891, Toulouse-Lautrec had already painted a number of large interior dance hall scenes at the Moulin Rouge, in his inimitable manner. However, for the poster he needed to adopt a more direct and dynamic style.

The poster isn’t only remarkable in that it was the first Toulouse-Lautrec had designed, but also for being the artist’s first experience of the lithographic printing process. At that time, Toulouse-Lautrec rarely exhibited his paintings and the Moulin Rouge poster thrust him into public view.

The version shown here, from the Musée Toulouse-Lautrec in Albi, is missing a narrow strip of the top edge but the two large, separate sheets which make up this poster can easily be seen from this reproduction. The repeated stamp in the shape of a cross on the yellow area to the left of ‘La Goulue’ is the dance hall’s official mark and the one below the ‘M’ of ‘Moulin Rouge’ signifies that the official duty on the poster has been paid.

Simplicity of Design

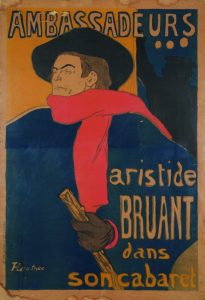

Toulouse-Lautrec produced a series of four striking posters for Aristide Bruant, who was a celebrated Montmartre cabaret singer. One poster was used to advertise Bruant’s guest appearance at the renowned Eldorado café-concert. The simplicity of the design, the cropped and framed image and the way in which Bruant’s extrovert character and bulky form were captured through the use of broad brushstrokes, were in complete contrast to the more delicate and painterly works of Jules Chéret.

Henri de Toulouse- Lautrec, Ambassadeurs. Aristide Bruant dans son Cabaret, 1892 / Musée Toulouse-Lautrec

Toulouse-Lautrec designed a similar poster for Bruant’s appearance at the rival Ambassadeurs café-concert but the resulting poster met with disapproval from the establishment’s manager. For his part, Bruant insisted that they should be used to advertise his appearance or he wouldn’t perform. The resulting affiche, which was greatly admired by the public, was pasted up all over Paris and inside the Ambassadeurs itself.

In total, Toulouse-Lautrec only produced 31 affiches illustrées. With many of these he adopted a practice of flattening forms and distorting perspective, influenced – as were many other artists of the time – by Japanese woodcuts. By embracing both the lithographic print medium and the commercial restrictions imposed by the format, his works became the touchstone for generations of poster artists.

In their different ways, both Jules Chéret and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec made a major contribution to the very existence of poster art, a form which was to become an enduring phenomenon across the western world throughout the next half-century.

Poster Museums: Where to see France’s finest affiches illustrées

Musée des Beaux-arts de Nice: Chéret lived out his latter years in Nice, passing away in 1932. The Musée des Beaux-arts de Nice was opened in 1928 as the ‘Palais des Arts Musée Jules Chéret’. 33 ave des Baumettes, 06000 Nice, Tel: +33 4 92 15 28 28. www.musee-beaux-arts-nice.org

MATOU (Musée de l’Affiche de Toulouse): Boasting an archive of some 18,000 posters and claiming to be “the only regional museum of this kind in France”, MATOU is currently closed for a complete refurbishment and will reopen in 2016. 58 allées Charles-de-Fitte, 31300 Toulouse, France. Tel: +33 5 81 91 79 17. www.centreaffiche.toulouse.fr

Musée Toulouse-Lautrec: Housed in Albi’s magnificent Bishop’s Palace, this museum’s collection includes all 31 of Toulouse-Lautrec’s posters plus many of his preliminary drawings, not to mention many of the artist’s greatest paintings. Palais de la Berbie, Place Sainte-Cécile, 81000 Albi, Tarn, France. Tel: +33 5 63 49 48 70. www.museetoulouselautrec.net

Musée des Arts Décoratifs: Département de Publicité /Graphisme. Houses around 100,000 affiches illustrées plus over 20,000 French and foreign film posters. 107 rue de Rivoli, 75001 Paris. Tel: +33 1 44 55 57 50. www.lesartsdecoratifs.fr

Centre Internationale du Graphisme: This archive began with a collection of 5,000 posters donated to the town of Chaumont in 1905. An international poster competition takes place on an annual basis which has contributed towards a contemporary poster collection of more than 40,000 items. 7/9 avenue Foch, 52000 Chaumont. Tel: +33 3 25 03 86 80. www.cig-chaumont.com

From France Today magazine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *