The Brasserie Man

What is it about brasseries?

As soon as you enter a brasserie in France, you are struck by a feeling of timelessness. You’re ushered to a table by a garçon de café with a long, white apron, black bow tie and a quirky sense of humour. He seems to glide effortlessly amid the hustle and bustle of the busy interior and settles you into a cosy corner made more intimate by the stained-glass partition that boasts an elaborate hand-painted scene in the style of Toulouse Lautrec or a simple fleur de lys. You gaze around at the tarnished candlesticks and glamorous chandeliers and yet there is nothing grand or intimidating about being here – there’s too much laughter and conviviality in the air for that. And it occurs to you that brasseries are something of a paradox: sophisticated yet informal, chic yet unpretentious, boisterous yet elegant.

Popular for more than a century, brasseries are the fabled haunt of artists and writers, the meeting place of politicians and prime ministers, an attraction where both tourists and locals alike linger to see and be seen. But it’s not for the fashion or the frivolity that they gather here – it’s for the food.

How it all started

The word ‘brasserie’ actually means ‘brewery’ in French. In 1864, Frédéric Bofinger, a brewer from Alsace in northeastern France, made his way to Paris and opened a tiny bar in the heart of the Marais and Faubourg Saint-Antoine area. It served little more than draught beer and sauerkraut. At that time, people were moving to Paris from war-torn Alsace in search of work, so there was a ready market. Beer on tap was unheard of in Paris back then and the quality of the sauerkraut was second to none. The combination took the city by storm and in no time brasseries were springing up all over Paris. The rest of France soon followed, and I think, for this reason, Bofinger could rightly claim to be the father of the Parisian brasserie. What started as a smoky bar filled with Alsatian refugees grew into a magnificent dining room with polished wood, gleaming brass and a stained-glass dome.

Brasseries are popular because the food they serve is homely, heart-warming and delicious and they will often serve everything from early breakfasts right through to late suppers in the small hours. Among the famous brasseries in Paris are: Bofinger, La Coupole and Brasserie Lipp, to name but a few. However, no matter where you are in France, if you find a good brasserie, you will find a good meal – and you won’t have to pay a fortune for it either. There are plenty on main streets, but the best ones are often tucked away down side streets and hidden behind porchways. Some brasseries will be modern and chic and some laden with so much history they are practically national monuments. How many restaurants can boast the illustrious likes of Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Salvador Dalì, Henry Miller, Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse among their clientele? Well, La Coupole can. Few people take a trip to Paris without visiting this renowned brasserie at least once.

From region to region

Brasseries make the most of local produce. There is a kind of regional pride, which ensures that you will always be served the best of whatever is grown or produced in the region. So eating in a brasserie in the South of France is a very different experience to eating in one in, say, Brittany. They all promote their own regional classics, often alongside well-known dishes from other areas. In Franche-Comté (my region), it could be Morteau sausage with sautéed potatoes and melted Vacherin Mont d’Or cheese. Up the road in Alsace, it could be choucroute (sauerkraut) or baeckeoffe (a kind of hotpot of potatoes, onion and pork). In Brest in Brittany, it could be seabass baked in a sea-salt crust, and in Paris it might be coq au vin. And if you are in one of France’s great brasseries, you will probably find all these specialities on one menu. Whatever region you find yourself in, brasseries will always offer a great variety of food.

Actually, cooking French food doesn’t need to be complicated, and bringing brasserie dishes into the home is returning them to their rightful place. After all, this is where most of them started, as most popular regional dishes served in brasseries would originally have been firm family favourites. For example, if you lived in Nancy in Lorraine, you would probably have eaten quiche lorraine; and if you lived in Bouches-du- Rhône, near Marseilles, it would have been bouillabaisse (a fish dish made with saffron and tomatoes), boudin noir (black pudding), coq au vin, tarte aux pommes (apple tart), crème caramel – all dishes that were cooked at home long before they were available in brasseries. Perhaps that’s the reason they have a special place in our hearts.

Food and family

The love of food has been with me as long as I can remember. My experience has come from many sources but the journey started with the wonderful home cooking of my grandmother. My first memory is of Grand-Mère’s kitchen on the farm my grandparents owned in Franche- Comté. I spent a large part of the summer holidays playing in the haystacks around the farm with my brother and sister. If we weren’t chasing cows, we were stealing cherries from the neighbouring farm, stuffing as many as we could into our mouths before the farmer could catch us. If I close my eyes, I can still recall the scent of freshly baked cakes luring me in from the fields. It wasn’t long before I was in that kitchen constantly: watching, learning, helping Grand-Mère prepare the fruit I’d collected. I’m told that, at the age of five, I stood in the middle of the kitchen and announced, ‘When I grow up, I’m going to be a chef!’

SOUFFLE AU FROMAGE

Preparation time 40 minutes, plus chilling and infusing

Cooking time 45 minutes

60g/2¼oz butter, softened

50g/1¾oz/heaped 1?3 cup plain flour

300ml/10½oz/scant 1¼ cups milk

1 bouquet garni, made with 1 parsley sprig, 1 thyme

sprig and 1 small bay leaf, tied together with kitchen

string

a pinch of freshly grated nutmeg

4 eggs, separated

100g/3½oz/¾ cup grated Cheddar cheese

100g/3½oz/¾cup grated hard cheese, such as

Comté, plus extra for sprinkling

cayenne pepper (or paprika for a milder flavour), for

sprinkling a few drops of lemon juice

60g/2¼oz mild, crumbly goat’s cheese, diced

sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

1. Mix 50g/1¾oz of the butter with the

flour until the mixture forms a smooth

paste. Transfer to a small dish, cover with

cling film and chill for 20 minutes.

2. Put the milk, bouquet garni and nutmeg

in a small saucepan and bring to the boil

over a high heat. Remove from the heat and

set aside to infuse and cool down for about

15 minutes until warm.

3. Strain the milk mixture into a large

saucepan and season with salt and pepper.

Reheat gently over a medium-low heat

to a simmer, then add the butter and flour

paste gradually, stirring until the milk thickens.

It should have a very smooth texture without

any lumps. Continue to cook the milk mixture

for a further 5 minutes, then add the egg

yolks one by one, stirring until combined

after each addition. Add 80g/23/4oz/²?³ cup

each of the Cheddar and Comté cheeses

and stir well. Season again with salt and

pepper and set aside.

4. Grease four individual 9x5cm/3½x2in

ramekins (or one round 18x8cm deep/7×3¼in

deep soufflé dish) with the remaining butter,

then coat the inside of the dishes with the

remaining Cheddar and Comté cheeses,

sprinkle a little cayenne pepper over and

chill to set while you finish preparing

the soufflé mixture.

5. Preheat the oven to 190°C/375°F/Gas

Mark 5 and rub a large clean bowl with

the lemon juice, then wipe dry. Put the

egg whites in the bowl and beat with a whisk

or electric mixer until medium to stiff peaks

form. Avoid overbeating or the mixture will

split and the soufflés will collapse. Whisk

half the egg whites into the cheese mixture,

then carefully fold in the rest, using a spatula,

until smooth and firm but light.

6. Spoon half the mixture into the ramekin

dishes, add the goat’s cheese and then

top with the remaining soufflé mixture.

Smooth the tops and wipe the inside borders

of the dishes clean with your thumb. Finally, sprinkle a little extra Comté over.

7. Bake the soufflés in the preheated oven for

10 minutes (12 minutes if you are making one

large soufflé), then lower the temperature to

170°C/325°F/Gas Mark 3 and bake for a

further 15-20 minutes until well risen, golden

brown and slightly trembling. Switch the oven

off and leave the soufflés in the oven for a

further 2-3 minutes, then remove from oven.

8. Serve immediately.

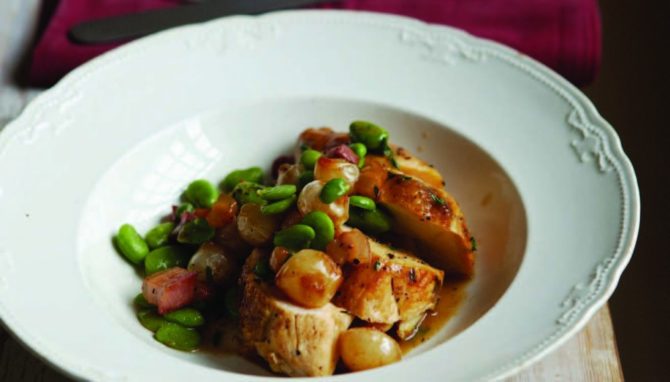

PAN-FRIED CHICKEN WITH GARDEN VEGETABLE & PANCETTA RAGOUT

Preparation time 20 minutes, plus making the stock

Cooking time 1 hour

1.5kg/3lb 5oz broad beans in the pods and then

shelled, or 400g/14oz/heaped 2 cups shelled broad

beans

2 tbsp sunflower oil

4 chicken breasts on the bone, 180g/6¼oz each

60g/2¼oz butter

2 garlic cloves, unpeeled and crushed with the flat

edge of a knife or your hand

1 small handful of summer savory (sarriette) or

2 thyme sprigs

14 spring onions, white bulb only and root cut off

a pinch of caster sugar

100g/3½oz pancetta, diced

1 tsp thyme leaves

4 tbsp shicken stock or water

sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

1. Bring a saucepan of lightly salted water to

the boil. Add the broad beans and blanch for

20 seconds, then drain and refresh

immediately in a bowl of ice-cold water and

drain again. Peel them and discard the outer

skins. I know it’s a fiddly job, but it’s worth

the trouble as it changes the flavour

completely. Set aside for your ragoût.

2. Warm the oil in a large heavy-based frying

pan or cast iron pan over a medium heat.

Season the chicken with salt and pepper and

cook, skin-side down and partially covered,

for 8 minutes or until golden brown and

slightly crispy. Turn the chicken over and add

a knob of the butter with the garlic and

summer savory sprigs. Reduce heat to low

and cook for a further 8 minutes. Transfer to

a serving dish, cover with foil and keep warm.

Set the pan aside for making the jus later.

3. To make the ragoût, melt a knob of the

remaining butter in a small frying pan on a

medium heat. Add spring onions and cook,

stirring frequently, for 5-6 minutes until light

golden. Season with salt and pepper and

sprinkle in the sugar. Add 4 tablespoons

water and cook over a low heat, partially

covered, for 12-15 minutes or until the water

has almost evaporated and the spring onions

are slightly glazed.

4. Meanwhile, bring a pan of water to the boil.

Add the pancetta and blanch for 1-2 minutes,

drain, refresh immediately in a bowl of cold

water and drain again. Don’t be tempted to

blanch the pancetta any longer or it will turn

too dry. Pat dry with kitchen towel.

5. Sauté the pancetta in a medium frying pan

over a medium heat for about 4 minutes until

slightly crispy. Stir in the broad beans, spring

onions and thyme leaves and keep warm.

6. To make the jus, add the stock to the

roasting pan and simmer for 2 minutes over

a medium-low heat. Add the juices that have

collected under your chicken and stir in the

remaining butter to give it a velvety shine.

7. Remove the 4 chicken breasts from the

bone, cut each breast into thick slices and

arrange on a plate. Divide the ragoût onto the

four plates, spoon the jus over and serve.

From French Brasserie Cookbook by daniel galmiche © Commissioned photography by Yuki Sugiura / duncan Baird Publishers

About the Author

Gastronomy’s ?best-kept secret,” Daniel Galmiche has earned prestigious Michelin stars at four of Britain’s top restaurants. ?The king of contemporary French cooking,” he trained under the tutelage of Michel Roux and is currently Executive Head Chef at The Vineyard in Stockcross, Berkshire. He was recently awarded the Relais & Châteaux Rising Chef Trophy 2011 award

Originally published in the June-July 2013 issue of France Today.

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *