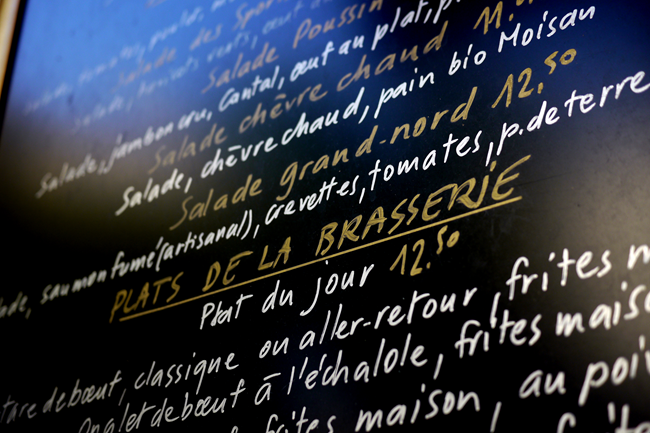

What Does France’s New ‘homemade’ Label Mean for French Restaurants?

After a failed attempt in 2015, a new “fait maison” (homemade) label is being introduced as compulsory for restaurants in France.

France is recognized worldwide for its gastronomy, from the homey bistro to the fine dining table. But behind this veneer hides a dirty secret, according to Alain Fontaine, president of the French Association of Maîtres-Restaurateurs. Of France’s 175,000 restaurants, only about 7,000 actually make all of their food in-house. Most, on the contrary, rely on industrial items: prepared steak tartare, frozen fries, bottled custard.

This issue is far from unfamiliar to movers and shakers in the industry, who, in 2014, created a label to help identify those actually making their food in-house. But this voluntary label is far from enough, according to Olivia Grégoire, Minister Delegate for Small and Medium Enterprise, Trade, Craft and Tourism, who is currently championing a new label which would stand out in two ways. Grégoire’s label would identify, not house-made items, but industrial ones – and moreover, it would be compulsory.

Industrialized food has pervaded the French landscape since the post-World War II era, a period known as the Trente Glorieuses or glorious 30. France’s first hypermarket opened in 1963, both signalling and facilitating the slow devolution of more traditional specialist shops in favour of industrialized goods. The arrival of restaurant chains, of which Wimpy became France’s first in 1961, contributed to the same shift in the restaurant world: lower costs led to lower prices, and traditional restaurants like brasseries and bistros shifted to prepared foods in order to be able to compete.

The current, official ‘fait maison’ logo

Smoke and mirrors

“Let’s never forget that restaurateurs are above all business owners,” says Fontaine. “They’re making an economic choice.”

These days, however, this choice is rampant. The proof, he says, is in the 3,600 members of his association, dedicated to traditional, quality-driven cooking – a mere two percent of all restaurants in France.

“Obviously, something’s going on in kitchens,” he says.

For most restaurateurs, the presence of industrial food on the landscape is less problematic than the smoke-and-mirrors that keeps the public in the dark.

“Your average client, when he goes to the supermarket, he’ll either buy fresh or industrial. He can turn over the can and see what he’s buying,” explains Xavier Denamur, proprietor of Les Philosophes in the Marais. “Why, the second you go into a restaurant, is that client no longer informed?”

Denamur has been fighting for restaurants to return to homemade food for nearly two decades. A one-man lobby in favour of transparency, he has written a book on the topic and has even combed through the trashcans of some of Paris’ professional kitchens to show the truth to consumers at home: bottled eggs, pre-prepared croque monsieur, French onion soup made with a powder.

“It’s tarnished, I’d say, the reputation of French restaurants,” he says.

This is the struggle that led to the current fait maison label, a solution developed with Carole Delga, former Secretary of State for Trade, Crafts, Consumer and Social Economy and Solidarity. With this law, restaurateurs use a symbol comprised of a pot with the roof of a house on top to signify that their food is made on-site with fresh ingredients.

Of course, there are a few exceptions. Fries, for example, can be cut fresh off-site. Frozen goods, originally precluded from the label, were finally allowed, following arguments that freezing was not processing but rather preserving.

But the fait maison symbol faded into oblivion within months: by April 2015, less than a year after it had gone into effect, Europe1 called it a “flop,” noting that clients didn’t trust it and restaurateurs barely used it. “You stay silent,” says Denamur.

Restaurants would be forced to state which items on their menu are processed © shutterstock

Transparency for consumers

The new label, as proposed by Grégoire in October, flips the script on the old one. Rather than a voluntary label showing which dishes are made in-house, the new obligatory label would require restaurateurs to identify any industrial preparations on their menus.

For Fontaine, this new approach will be far more effective for consumers, not just because of its clarity and concision, but also because it will be subject to inspections.

“Fait maison had no inspection, no sanctions,” he says. “So for consumers, this is more reassuring.”

Denamur hopes the new label will promote transparency for consumers, but also reward those who have long been doing things right, encouraging, he says, “real competition, not underhanded competition.” Many restaurateurs relying on industrially produced food, he says, often charge the same prices as Denamur – or even more. This, he posits, is to hide the fact that the product is being bought in.

“I’ve seen interviews where people say they’re selling their profiteroles for 20 euros because if they sold it at 12 or 13, people would know they were industrial,” he says. “So they sell them for as much or more than a restaurant making them for real.”

The new label is, of course, far from perfect.

“It doesn’t go far enough, but it is a good first step,” says Fontaine. While he doesn’t believe it will fully change the tides of industrialization, he does hope that it will push those who bring in just a handful of industrially prepared dishes to cut them from the menu and turn entirely to homemade.

“I think it could promote change,” he says. “A lot? Maybe not. But at the margins, yes. There might be a few thousand restaurants that will transition to wholly homemade. So yes, it could change things.”

Another issue pros have identified is the timing: The new label is proposed for 2025, after Paris hosts the Olympics. Chef Thierry Marx, President of the Union des métiers et des industries de l’hôtellerie (UMIH) is one particularly vocal proponent of an earlier rollout, telling le Figaro that the games “seem to us to be an extremely important spotlight on restaurateurs.”

Fontaine agrees. “There’s no reason for it to be after [the Olympics],” he says. “It would be stupid to not take advantage of it.”

Perhaps the most essential issue however is the arbitration the project must undergo before it takes its final form

“That’s what caused the first fait maison to fail,” says Fontaine, evoking the agri-food lobbies that managed to hack away at Delga’s original plan until it was a shadow of itself.

“In the next few months, Olivia Grégoire will need to be quite careful,” he continues. “We cannot have another failure.”

Even croque-monsieur were no longer always made fresh on site © shutterstock

Lead photo credit : © shutterstock

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in French food, French restaurant, news

By Emily Monaco

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *