Writers on the Riviera: The Fitzgeralds and the Côte d’Azur

“When your eyes first fall upon the Mediterranean you know at once why it was here that man first stood erect and stretched out his arms toward the sun. It is a blue sea; or rather it is too blue for that hackneyed phrase which has described every muddy pool from pole to pole. It is the fairy blue of Maxfield Parrish’s pictures; blue like blue books, blue oil, blue eyes, and in the shadow of the mountains a green belt of land runs along the coast for a hundred miles and makes a playground for the world.”

— F Scott Fitzgerald, How to Live on Practically Nothing A Year, The Saturday Evening Post, September 1924

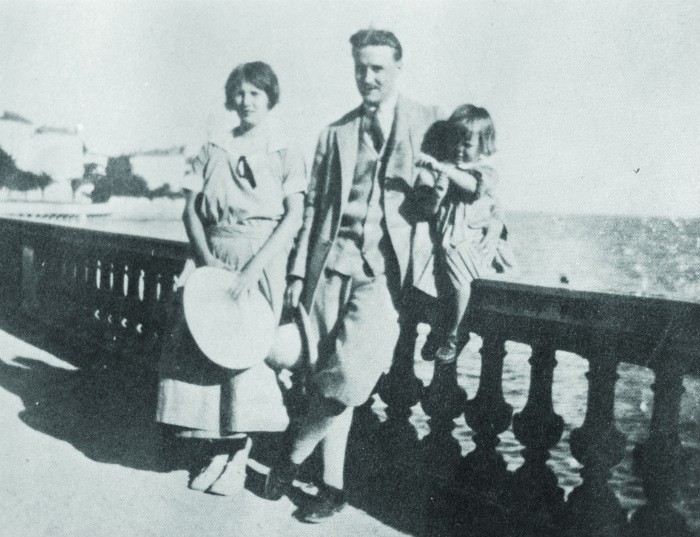

When F Scott Fitzgerald sailed across the Atlantic to France in 1924, accompanied by his wife Zelda and daughter Scottie, the idea was to escape to a place where they could ‘live on practically nothing a year’. The reason was glaringly simple: four years after the publication of his best-selling novel, This Side of Paradise (1920), which catapulted the writer to literary stardom and rendered him the hero of the Jazz Age, Fitzgerald found himself left with capital of just $7,000. No longer able to keep up with New York’s frenetic social life and the excessive partying that was keeping him from completing his third novel, The Great Gatsby, he made a decision. Fitzgerald and Zelda took temporary leave of their sumptuous home in Great Neck, Long Island, and their final destination would not be Paris, rather the “hot, sweet south of France”.

The Fitzgeralds on the Riviera. Photo credit: collection of John Michel Sordello

“We were going to the Old World to find a new rhythm to our lives,” Fitzgerald wrote, in How to Live on Practically Nothing a Year, his article about the adventure for The Saturday Evening Post. “With a true conviction that we had left our old selves behind forever.”

Back then, life was still relatively cheap on the French Riviera, particularly during the summer, since, as Fitzgerald quipped, it was “something like going to Palm Beach for July”. Come April, the visiting aristocracy closed their villas and wouldn’t return until winter, fleeing the high temperatures, mosquitoes and insalubrious sea breezes.

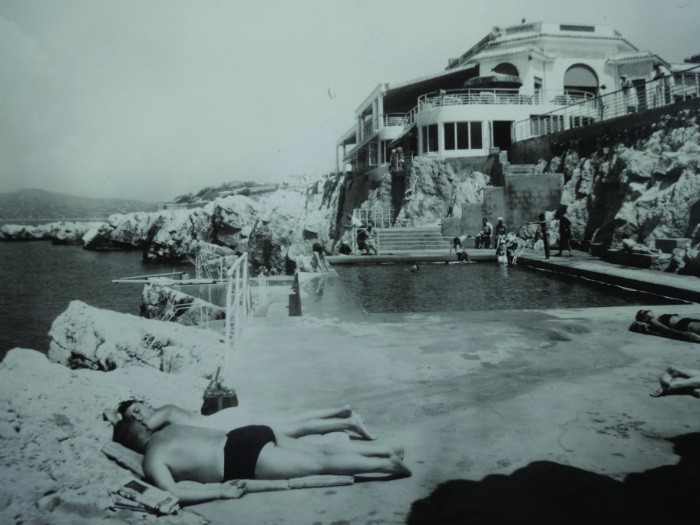

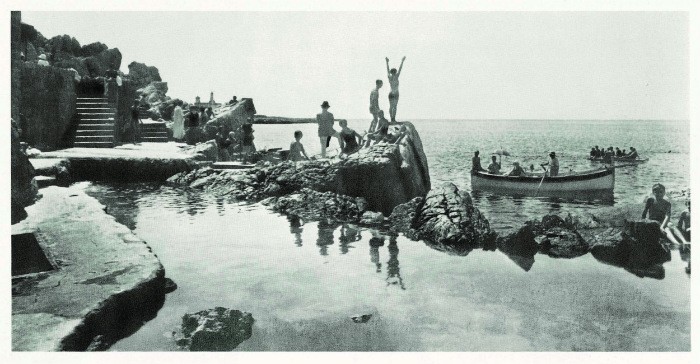

A vintage photo of the Eden Roc. Photo credit: collection of John Michel Sordello

In May, the Fitzgeralds took the train from Paris to the sleepy town of Hyères, knowing that Edith Wharton owned a house there. Finding it dreary and overrun with condescending British pensioners, their disappointment turned to joy when an agent showed them the Villa Marie, a charming property on a pine-shaded hillside in Saint-Raphaël, which Fitzgerald described as “a little red town built close to the sea, with gay red-roofed houses and an air of repressed carnival about it”.

“I don’t see why everybody doesn’t come over here,” Fitzgerald rhapsodised, tongue-in-cheek, in How to Live on Practically Nothing a Year. “I am now writing from a little inn in France where I just had a meal fit for a king, washed down with Champagne, for the absurd sum of sixty-one cents. It costs about one-tenth as much to live over here. From where I sit I can see the smoky peaks of the Alps rising behind a town that was old before Alexander the Great was born…”

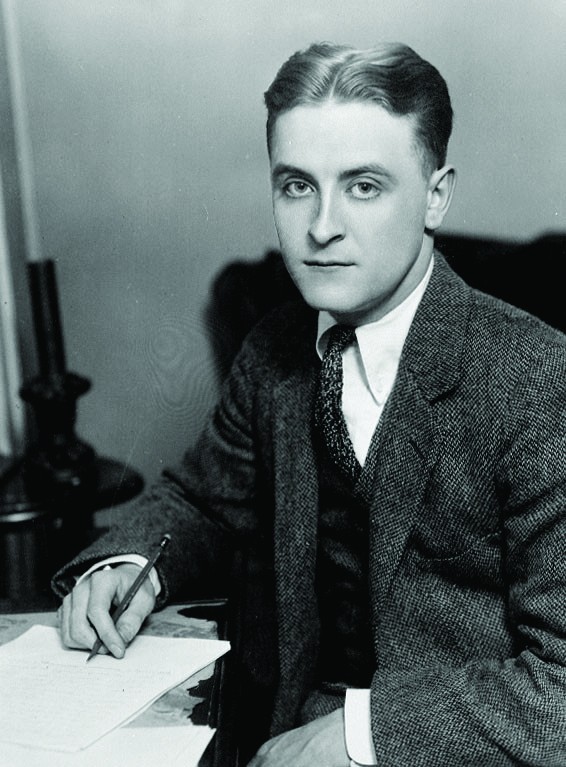

F Scott Fitzgerald in 1921

From June to October, Scott shut himself away in the Villa Marie, working on The Great Gatsby, while Zelda had a passionate but short-lived affair with a young French aviator, Edouard Jozan, whom she met on the beach.

“Saint-Raphaël marks the first real ‘crack’ in their marriage,” says Riviera-based Fitzgerald biographer, Jean-Luc Guillet. “Scott was haunted by Zelda’s betrayal, and his fear of losing his wife to someone else turns up both in The Great Gatsby and in Tender is the Night.”

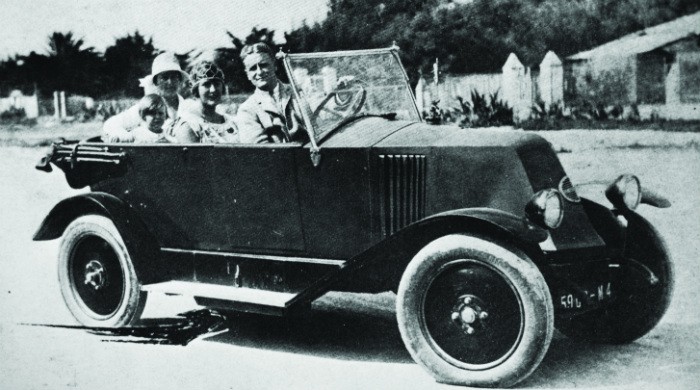

The Fitzgeralds in a car. Photo credit: collection of John Michel Sordello

At a dramatic moment in the former, Jay Gatsby tells Daisy’s husband, Tom Buchanan, “Your wife does not love you. She’s never loved you. She loves me”.

Blame it on those long idle afternoons and the balmy climate. In Zelda’s semi-autobiographic novel, Save me the Waltz (1932), emotions run high because the Riviera “is a seductive place” where “the blare of the beaten blue and those white palaces shimmering under the heat accentuates things”.

*********

For a much-needed distraction, the Fitzgeralds would take a jaunt in their little blue Renault, down the coastal road to the Cap d’Antibes – past the still spectacular red rocks of the Esterel and the Gulf of Napoule’s turquoise shallows – to visit their close friends, Sara and Gerald Murphy.

1920s photo of Eden Roc Cap d’Antibes. Photo credit: collection of John Michel Sordello

Best known as Fitgerald’s initial models for Dick and Nicole Diver in Tender is the Night (1934), the Murphys’ charisma is summed up in the novel’s opening chapters, which are set on the Plage de la Garoupe, on the Cap d’Antibes’ eastern side. Talking about the Divers and the Riviera, alcoholic American musician Abe North tells the recently arrived film starlet Rosemary Hoyt that “they have to like it. They invented it”.

Gerald Murphy, a wealthy heir to the Mark Cross luxury leather goods company, had moved to Paris with his family in order to study painting. His trendsetting qualities also extended to his modern creative sensibilities, as he produced avant-garde canvases and décor that can clearly be seen as a precursor to Pop Art. Accompanied by his elegant wife, Murphy discovered the enchantment of the Cap d’Antibes in the summer of 1922, when their friend Cole Porter invited them to stay in his rented villa, the Château de la Garoupe.

Aerial View of Hotel du Cap. Photo credit: Sordello

Deciding that they wanted to settle amid the Cap’s sleepy fishing villages, the Murphys returned the following year and convinced the owner of the seaside Hôtel du Cap-Eden-Roc – the model for the Hôtel des Étrangers in Tender is the Night – to keep it open for them during the summer.

While their new home, Villa America, was under construction, the Hôtel du Cap-Eden-Roc became the Murphys’ headquarters and a place to invite their friends. Today, the Hôtel du Cap-Eden-Roc, it’s one of Europe’s glitziest places to stay. Their charmed circle included the likes of neighbours the Count and Countess de Beaumont, who lived at the splendid Villa Eilenroc; Picasso and his mother, Senora Ruiz, and ballerina wife, Olga; the silent movie icon Rudolf Valentino; and Gertrude Stein.

*********

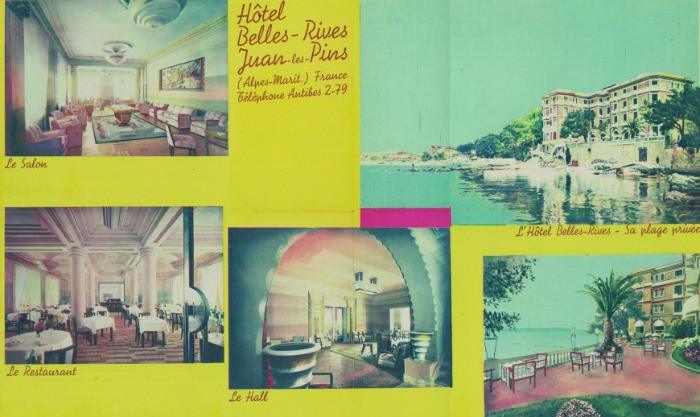

The facade of the Belles Rives. Photo courtesy of courtesy of the Hotel Belles Rives

With their marriage under strain, Antibes was a welcome escape for the Fitzgeralds, whose notorious, alcohol-fuelled antics were on a par with the misbehaviour of rock stars at their most dissolute. On a mutual dare, they once disrupted the Murphys’ party at the Hôtel du Cap by diving off 35-foot-high rocks into the pitch-black Mediterranean.

On another night, Zelda stripped off her black lace panties and tossed them to her hosts, encouraging an impromptu skinny-dip in the pool with other inebriated guests. On a more sobering occasion, Zelda downed a large quantity of sleeping pills and then had to be walked around the hotel’s grounds until morning.

Although the Fitzgeralds returned to New York in the autumn, the enticing gaiety of the Riviera brought them back in the summer of 1926. In the wake of Gatsby’s success, Scott rented the Villa Saint-Louis in Juan-les-Pins, bragging to his friends in New York that he’d found a house on the shore with a private beach, conveniently situated near the casino. It was there that Fitzgerald began working on Tender is the Night, which would take him seven years to finish.

In 1929, the Art Deco villa was transformed into the small, family-run Hôtel Belles-Rives. Its period furnishings, frescoes and fumoir have all been meticulously preserved by the current owner, Marianne Chauvin-Estène.

The Bar Fitzgerald, named for the author. Courtesy of the Hotel Belles Rives

At the Villa America, the Murphys’ modernist, 14-room home – replete with a black-tiled living room, a sun deck on its flat roof and a exotic garden – the Fitzgeralds mingled with the most prominent figures of the European arts scene: Cocteau, Léger, Man Ray, Stravinsky, Diaghilev and many more. The literary names who were regular guests included Ernest Hemingway and his wife, Hadley (later, also Pauline Pfeiffer, his second spouse), John Dos Passos, Dorothy Parker, Archibald MacLeish and Robert Benchley.

“The air smelled of eucalyptus, tomatoes and heliotrope,” recalled Dos Passos, describing the languid summer evenings on Villa America’s terrace. Gerald Murphy, smartly dressed in spats or white ‘bucks’ and a striped sailor jersey, made elaborate cocktails for his guests, as Dos Passos put it, “like a priest preparing mass”, inventing concoctions “with the juice of a few flowers”.

At one of these famous soirées, which was later immortalized in Tender is the Night, Scott Fitzgerald behaved even worse than usual – he insulted guests, then picked up a sorbet-sodden fig and threw it at the bare shoulders of his hosts’ friend, the Princesse de Poix. Once, Fitzgerald started to smash Sara Murphy’s handblown wineglasses so he was escorted to the door and the couple banished him from the Villa American for weeks.

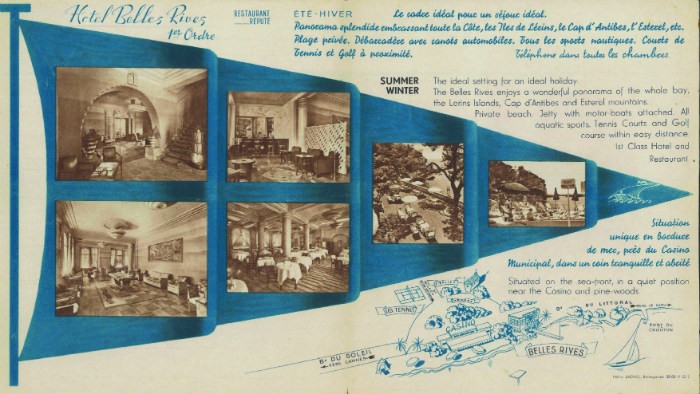

A vintage postcard of the Hotel Belles.

Monte Carlo was a perfect destination for the “excitement eaters”, as Zelda referred to herself and Scott. They’d take the winding Grande Corniche “through the twilight with the whole French Riviera twinkling below” and spend the evening gambling at the Casino. If Scott had forgotten his passport, he’d pretend to faint in front of the gaming room’s guard, hoping that they’d still let him in.

Another glamorous hotspot was the art-filled restaurant La Colombe d’Or in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, which was already a celebrity haunt. One evening, while dining on the terrace, Scott spotted Isadora Duncan at the next table and went to pay his respects. Afterwards, Zelda was jealous and, in retaliation, threw herself down a flight of stone steps.

*********

When it came to dining, the Fitzgeralds avoided elaborate French cuisine and despised l’ail – “the only garlic that can be put over us must be administered in sleep”. Even in the most exclusive restaurants, Scott would wave away the waiter and order a club sandwich in his heavily-accented French.

During the couple’s last summer on the Côte d’Azur, in 1929, the US Stock Market had crashed and the mood shifted drastically. The Fitzgeralds holed up at a modest villa in Cannes, avoiding the Hôtel du Cap which, to Scott, had become a celebrity circus where silk pyjama-clad patrons used the pool “only for a short hangover dip”. Somerset Maugham would also satirize the hotel’s raging social scene in his short story, The Three Fat Women of Antibes.

Zelda, already showing signs of mental strain, was still determined to become a ballerina. Staying at the Hôtel Beau Rivage on the Promenade des Anglais in Nice, they went “to the cheap ballets of the Casino on the jetée” while desperately trying to save money.

A vintage postcard of the Hotel Belles Rives

By the time that Tender is the Night was published, in 1934, the Murphys and the Fitzgeralds had long since returned to America, and both families endured a series of tragic events. The Murphys lost both of their young sons, Patrick and Baoth, to illness, while Zelda was in and out of sanatoriums, grappling with severe mental breakdowns.

What remained of those years, as evoked by Fitzgerald, was the glow of a golden era on the Riviera, when a handful of American expats invented an enduring lifestyle of sunbathing, swimming and partying on the Côte d’Azur.

Gerald Murphy later wrote to Fitzgerald, “I know now that what you said in Tender Is the Night is true. Only the invented part of our life – the unreal part – has had any scheme, any beauty”.

American arts and travel author Lanie Goodman has been based in the South of France since 1988. She’s written for the likes of Condé Nast Traveler, the Los Angeles Times and The Guardian.

From France Today magazine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *