An Exclusive Excerpt from “Marie Antoinette’s Darkest Days”

From the splendours of Versailles to the dungeons of the Conciergerie, Will Bashor charts the coquettish queen’s harrowing final weeks in solitary confinement, awaiting her call with Madame Guillotine. Here, the award-winning author offers a rare glimpse into her dramatic downfall from wife of the French monarch to the anonymous prisoner, Widow Capet, No. 280.

_________

Gone are the days of extravagant balls, the towering pouf hairstyles, and the lavish court life of Versailles. Queen Marie Antoinette, the daughter of Empress Maria Theresa of Austria, is imprisoned in the Temple prison with her sister-in-law Madame Élisabeth, her daughter Marie-Thérèse, and her eight-year-old son Louis Charles, the uncrowned King Louis XVII of France—uncrowned since the execution of his father Louis XVI on January 21, 1793.

The month after Louis XVI’s rendezvous with the guillotine, and unbeknownst to Marie Antoinette, the insurrectionary delegates of the government of Paris asked that the queen be separated from her family. She could then be transported to the Conciergerie prison for a speedy trial by the newly created Revolutionary Tribunal. Amid laughter and murmurs, the delegates were amazed to learn that after the death of Louis XVI the government still provided his widow with valets de chambre to “empty her chamber pot” in the Temple.

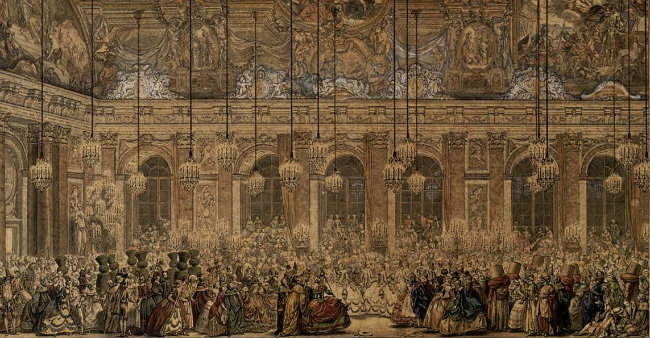

Bal masqué donné pour le mariage du dauphin (Jaconde database). “Masked Ball.” Author: Charles Nicholas Cochin (1715-1790). Public Domain

Since the king’s death, eight cooks still “sumptuously” prepared the queen’s table at the Temple, and the young Louis Charles was often found sitting on a cushion at the head of the table and addressed as “sire.”

Despite her imprisonment, the queen remained optimistic of a better future. When the queen’s sister-in-law less enthusiastically asked her to face reality, the queen responded, “I have great hope in the fickleness of the French people and the outcome of the war; time and the allied powers will be on my side.”

Unfortunately, the allied powers’ influence was waning, despite the French people’s fervor; time was running out for the queen. The National Convention was already proposing that she be accused of treason and brought to justice. Although the initial request to remove Marie Antoinette from the Temple and send her to the Conciergerie for judgment was denied, the government still remained apprehensive about the prince’s presumptuous claim to the empty throne.

Portrait of Marie Antoinette. Jean-Baptiste Gautier Dagoty (1740-1786)

After the execution of his father, the young heir Louis Charles could now be targeted, but how would the government dispose of an innocent child who could hardly be convicted of any single crime against France? With each day that passed, however, the young heir was becoming increasingly more of a threat to the revolutionaries. King Louis XVI was now out of the picture, but a delegate warned that the young prince was “a hostage that must be preserved carefully.” The danger was not what the boy was—but what he could become.

To put such fears to rest, the child was ordered separated from his family by a decree of the National Convention and confined to another cell in the Temple tower. The young heir would not be assassinated; the revolutionary government was farsighted enough to realize such a cruel measure would be a mistake. Instead, the jailers would destroy the child’s health by depriving him of fresh air, light, proper exercise, and wholesome food and by keeping him in a state of fear and fever-breeding filth in his cold, dark cell. Then, when necessary, the convention could present a “moping little idiot, whose diseased body and vacant stare of imbecility would make him such a sorry and pathetic choice for a monarch that the people would turn away in horror.” On July 3, this infamously cruel order was executed.

Portrait of Marie Antoinette. Jean-François Janinet (1752-1814), after Jean-Baptiste Gautier-Dagoty. Public domain.

If Marie Antoinette’s Christian principles had helped her endure all the pain and sacrifices in her life, her queenly pride helped her bear all the humiliation. But now any illusion that she would never be separated from her children was dispelled.

In the days to follow, the child was occasionally allowed to take a short walk on a ledge of the Temple tower, and Marie Antoinette would sit for hours just to catch a quick glimpse of him through a small slit in the wall—but even this flash of solace did not last long.

When the convention received the shocking news that a European conspiracy threatened French liberty on August 1, the revolutionary Committee of Public Safety reported that the time had come “to eradicate every trace of royalty.” It called for the convention to adopt violent measures, including the immediate transfer of Marie Antoinette to the Conciergerie to appear before the Revolutionary Tribunal. In the middle of the night, at three o’clock in the morning, the queen was escorted under heavy guard to her new prison.

Widow Capet, Prisoner No. 280 in the Conciergerie. Generations of authors have revelled in reliving the Marie Antoinette’s reign amid the splendors of the court of Versailles and the Petit Trianon, but few have ever found the space (or perhaps the courage) in their voluminous biographies to narrate her final imprisonment in the Conciergerie.

This chapter of the queen’s life begins when she is torn from her family’s arms and escorted to the Conciergerie, a thick-walled fortress turned prison. It was then known as the “waiting room for the guillotine” because prisoners only spent a day or two here before their conviction and subsequent execution. The queen surely knew her days were numbered, but she could never have known that two and a half months would pass before she would finally stand trial and be convicted of the most ungodly charges.

Coiffure à l’Indépendance ou le Triomphe de la Liberté Author: Anonymous. Public domain.

Marie Antoinette’s reign amidst the splendors of the court of Versailles is a familiar story, but her final imprisonment in a fetid, dank dungeon reeking of rat urine is a little-known coda to a once-charmed life. These seventy-six days can only be described as a cruel mixture of grandeur, humiliation, and terror; they were surely the darkest and most horrific of the fallen queen’s life.

Very few requests from wardens to assuage the queen’s incarceration were ever acknowledged by the revolutionary government. Instead, it documented and monitored all expenses incurred during her incarceration. Although the list was rather short, it did cover basic necessities such as meals—whether she even ate them at all because she was suffering from cervical hemorrhaging at the time.

There was no mention of breakfast but her loyal maid, Rosalie, reported that she often provided the queen with a cup of chocolate and a roll in the mornings. For lunch the government allotted her coffee, and for dinner she received broth, a plate of boiled vegetables, chicken, and dessert. On some days she was allowed duck and pâté; in fact, one of her sympathetic wardens would occasionally shop for the duck himself, knowing it to be one of the queen’s favorite dishes.

The government also provided two mattresses, a folding bed with a bolster, a woolen blanket, and a cane chair. A new bidet trimmed in red basane was also purchased for the queen.

Other expenses included book rentals, of which The Travels of Captain Cook was her favorite; two bonnets; ribbon and silk lining for a skirt; ribbon for her shoes and hair; and a bottle of special water for her teeth. One very important expense, however, was not recorded until after the queen’s execution.

According to some historians, it was two weeks before the body of Marie Antoinette was laid to rest in the Madeleine cemetery. What happened to her body during this time? No doubt, it was thrown in the grass in a corner of the cemetery, forgotten and awaiting orders to be interred, which never came. Finally, the gravedigger Monsieur Joly took it upon himself to dig a hole and bury the queen’s remains. Considering the loathing of the revolutionary government for the queen, Monsieur Joly must have been very courageous to bury the body and even more courageous to dare present his bill—the only existing document about the queen’s burial.

It is not known if Monsieur Joly was paid for his benevolence because the people’s hatred for Marie Antoinette did not end with her death. Immediately after her execution, the queen’s enemies distributed pamphlets around Paris, saying that the Statue of Liberty at the foot of the scaffold turned its head and smiled when the blade of the guillotine fell—just a few steps from the gardens of the Tuileries where the queen’s children once played.

Photographs selected from the book by France Today.

Subscribe to our mailing list

Sign up to the free France Today newsletter to get all the best France related content and competitions sent directly to your inbox.

Find out more here.

_________

Marie Antoinette’s Darkest Days: Prisoner No. 280 in the Conciergerie, written by Will Bashor, published by Rowman & Littlefield. Purchase the book on Amazon below.

Purchase your edition here.

En grand habit de cour by Jean-Baptiste André Gautier-Dagoty. 1775. Source: Wikipedia, public domain.

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY