A Fallen Nobleman: Following the Footsteps of the Marquis de Sade in France

Chloe Govan discovers the dark heart of the Marquis de Sade, tracing his footsteps through Paris, Provence and an infamous fortress christened the Bastille of the Alps

Nestled in the majestic foothills of the Savoie valley, a deceptively quiet mountain fortress is hiding dark secrets – and they are about to be uncovered. In a split second, a dishevelled, lawless aristocrat leaps through an open window and straight onto the back of a waiting horse – a stunt that might not have been out of place at the Cirque d’Hiver Bouglione. The silence of the Alpine wilderness surrounding him is broken only by his frantic breathing and the pounding of hooves galloping along the route to freedom.

While the triumphant locals of Provence are toasting his incarceration, gloating over headlines that brand him “depraved”, “despicable” and “an outrage to public decency”, the monster of their nightmares is on the road back home.

This is the escape scene of the Marquis de Sade, a man whose antics were so notorious that the term “sadism” was coined after him.

Once a respected, blue-blooded nobleman, he now faced condemnation for a catalogue of abuse charges, from poisoning prostitutes to raping and torturing homeless beggars. Where had it all gone so wrong?

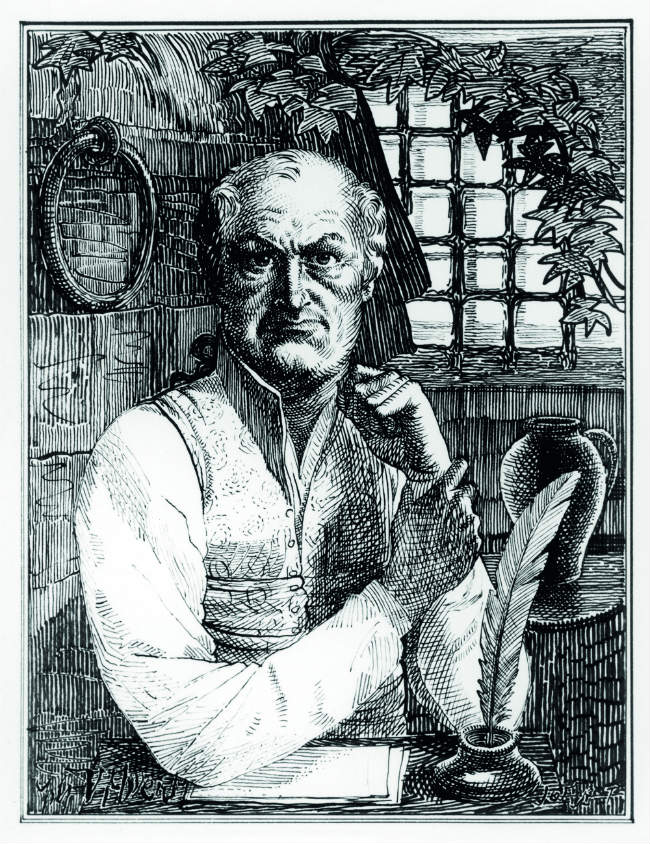

Portrait of De Sade by Mary Evans. Wikimedia Commons/ Public domain

Perhaps the answer lies in his early life. It had begun in palatial luxury, ensconced in an all-expenses paid apartment at the Condé Palace in Paris. This wealth came courtesy of his mother, a relative of the royal family and a lady-in-waiting and babysitter to the Prince de Condé. De Sade would later portray himself as a domineering, overly entitled child whose morals had been polluted by power and privilege. He recalled believing that the “whole universe” existed purely to satisfy his whims and that he should need “only to think them to have them satisfied”.

The consequences of his arrogance were soon akin to a high-society soap opera for the medieval era. Even at the tender age of four, he would display traits of anarchy and rebellion against the higher-ranking boy who commanded so much of his mother’s attention. Disinterested in obeying the social hierarchy, an enraged De Sade repeatedly punched the pampered prince in a fit of jealousy – an action which saw him torn from his mother’s arms and banished from the regal household.

He went to live with his uncle, who, although ostensibly a priest, was ruled by a voracious sexual appetite and often staged orgies in a makeshift Gothic bordello in the basement of his house. Meanwhile, by the time De Sade was seven, his mother had left the lap of luxury and enrolled herself in a convent on a street with the eyebrow-raising title of rue d’Enfer (Inferno), not far from the city’s catacombs. Why she would abandon a life of grandeur for the austerity of a convent is uncertain, although if her nun’s vows had meant as little as the priesthood had meant to her brother, she may well have lived a colourful life nonetheless. Equally intriguing is the fate of De Sade himself. With a nun as a mother, who could have imagined that the young marquis would later be regarded as being so brutally violent?

Chateau de Miolans. As prisons go, at least the Bastille of the Alps had a nice view. Photo: Jerome Hugot

STRICT MORAL CODE

His domineering traits continued even after marriage and children – he infamously claimed that he would prefer to see a lover dead than sexually disloyal. Hypocritically, however, his strict moral code did not apply to himself, and he would regularly roam the streets of Paris looking for prostitutes to lure back to his château.

He would dine at the opulent Grand Véfour, a restaurant embellished with jewel-encrusted mirrors and sumptuous velvet seats, as a prelude to a night of decadence. The location, alongside the Palais Royal gardens and their notorious brothels, was perfect. The area’s powerful owner forbade access to the police, making it a magnet for mafia-level immorality. The combination of cuisine and courtesans was a powerful draw for De Sade, who was addicted to satisfying his appetites for both food and flesh.

However, as it turned out, his predilections were too extreme even for Paris and its decadent 1700s pleasure scene, and – after scores of furious prostitutes led complaints that he had whipped them – he was imprisoned. Ironically, it was not others he’d lashed to earn his first spell of incarceration, but himself. The God-fearing Jeanne Testard had been expecting a simple cash-for-sex transaction. Instead she watched him stamping on a crucifix and screaming blasphemies while self-flagellating with a cat-o’-nine-tails. Perhaps unsurprisingly, she reported him to the authorities.

Château de Mazan. Photo: R. Chouraqui

ECHO CHAMBER OF INSULTS

No sooner was he released than he was back to depravity. One Easter Sunday, he kidnapped a homeless beggar, promising her an income as a housekeeper. Instead, he locked her in a room, allegedly lacerated her buttocks with a knife and then poured boiling wax into her wounds. All the while, he took delight in taunting her religious faith. If God existed, he challenged, where was His divine intervention now?

When questioned about his antics, De Sade was always nonchalant. Yet, claiming that the victim was a prostitute, not a beggar, barely saved his ailing reputation and it was time to retreat. In a bid to escape the echo chamber of insults, he fled to a family home in the heart of the Provençal countryside – which is now a hotel known as the Château de Mazan.

As I wander into the foyer, I am greeted by an apparition of De Sade himself. Up close, this delightfully creepy mannequin stands tall, dark and not very handsome, plaster peeling from his comedically large chipped nose. He waits, ghostly still, outside the dining room, as if ready to seat guests for a plate of his favoured quail meat, a glass of absinthe – always his poison of choice – and a front-row view of his latest theatrical performance. The dilapidated figure might be a vastly exaggerated caricature of his likeness, but it makes for an essential photo opportunity nonetheless.

The sculpture of De Sade at Château de Lacoste. Photo: Chloe Govan

HORROR OR PERVERSITY

This 30-room mansion, like its many olive trees, is almost 300 years old, and the owners have preserved its traditional Provençal architecture and charm. Plus, despite the property boasting enough bird statues to resemble an Alfred Hitchcock film set, there are few traces of bygone horror or perversity here. In fact, every window reveals an idyllically peaceful view.

Shrouded in secrecy at this hidden retreat, De Sade was no longer a loathed Parisian provocateur, but a country gent away from the prying eyes of the city. It was in this house that he would reinvent himself as an aspiring actor, creating and performing his own plays. Performances would also take place at the sprawling family château at Lacoste – although, in De Sade’s day, the 12-hour journey by horse and carriage from Mazan was a theatrical affair in itself. Today, visitors can follow the same path by car in less than an hour.

The gateway to Lacoste village. Photo: R. Chouraqui

In its prime, Lacoste hosted orgies and its own 80-seat theatre – although later, after De Sade became bankrupt and destitute, his once grand château would be abandoned to crumble into ruins. It has since been rescued by fashion designer Pierre Cardin, but anyone hoping for lavish renovations will be sorely disappointed. Though he offered to sell his fashion brand for a billion dollars, Cardin refuses point blank to part with the château, and remains adamant about keeping it “as though it had never been touched”. Consequently travellers can amble around the hilltop summit admiring it in its authentic state.

The village of Lacoste. Photo: Chloe Govan

UNORTHODOX DESIRES

The most prominent reminder of De Sade’s notoriety is a sculpture of a caged man alongside the ruins, his head behind bars. This imagery represents a libertine’s struggle and his enslavement to his unorthodox desires – ones that the outside world would, of course, never embrace.

Yet perhaps the most impressive stopover of all on the Marquis de Sade trail is the

Château de Miolans, a three-hour drive northwest into Alpine territory. This was the

scene of the dramatic horseback escape. De Sade had stood accused of poisoning a

group of prostitutes, although forensics would later reveal that they had merely over-indulged in the aphrodisiac Spanish Fly. If it had been anyone else, the episode might have been written off as the equivalent of a hangover, but by now De Sade’s reputation preceded him and he was imprisoned without trial. The tables had drastically turned – whereas popes had once gifted De Sade’s family with fortresses, he was now locked away in one.

Château de Miolans. Photo: Chloe Govan

Plus, just as he had juxtaposed pleasure with pain, this “Bastille of the Alps” often portrayed a bizarre dichotomy of its own, doubling as a palatial paradise above and a torturous den of entrapment below.

Some residents suffered impenetrable solitude, chained up in torture chambers unambiguously labelled ‘Enfer‘. Naturally, however, De Sade’s wealth and status afforded him far more privileges than the average criminal. When he was not gorging on gourmet cheeses sent by his ever-suffering wife, in the murky depths of his imagination he was feasting on flesh – and he would write feverishly about it. Arguably, the prison guards fared worse than the pampered prisoner – as “mere peasant workers”, they were obliged to sleep on the cold stone floor outside his cell each night. Plus, while he resided in the Grande Espérance room, just underneath the Paradis wing at the top, the less fortunate languished in the labyrinth of underground dungeons five floors lower.

Borie (a dry-stone cabin) on the grounds of the Château de Miolans. Photo: R. Chouraqui

DREADED OUBLIETTES

Wandering the ramparts today, it seems inconceivable that the place was once home to such horror. Visitors can explore the full scope of the prison, from the gunpowder stores to the dungeons and dreaded oubliettes. Graffiti marks are still etched onto the walls of the treasury, although there is no pornographic poetry by De Sade. Yet the most atmospheric pleasure is found in scrambling through the dark passageways and scaling the steep spiral staircases. The reward for the climb is a jaw-dropping panorama over mountains from Mont-Blanc to Belledonne.

De Sade’s notoriety later continued with a stint in Vincennes, where he again enjoyed enormous privilege for a prisoner, and installed a 600-volume library inside his cell. He also served time in Paris’s Bastille, where one of his manuscripts was almost lost during the Revolution. His opponents would argue it was just as well, as the erotic novels he wrote depicted every possible taboo, from rape and incest to graphic torture. Some characters enjoyed “combining sex with murder” and, according to De Sade, his tales were the “most impure ever told”. Even the disembowelment of young children was not beyond the scope of his feverish imagination. Eventually he was committed to an asylum near Paris, where he would spend the remainder of his life.

From France Today magazine

The mannequin of De Sade at the Château de Miolans. Photo: Chloe Govan

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

By Chloe Govan

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY