Looking for Les Misérables in Paris

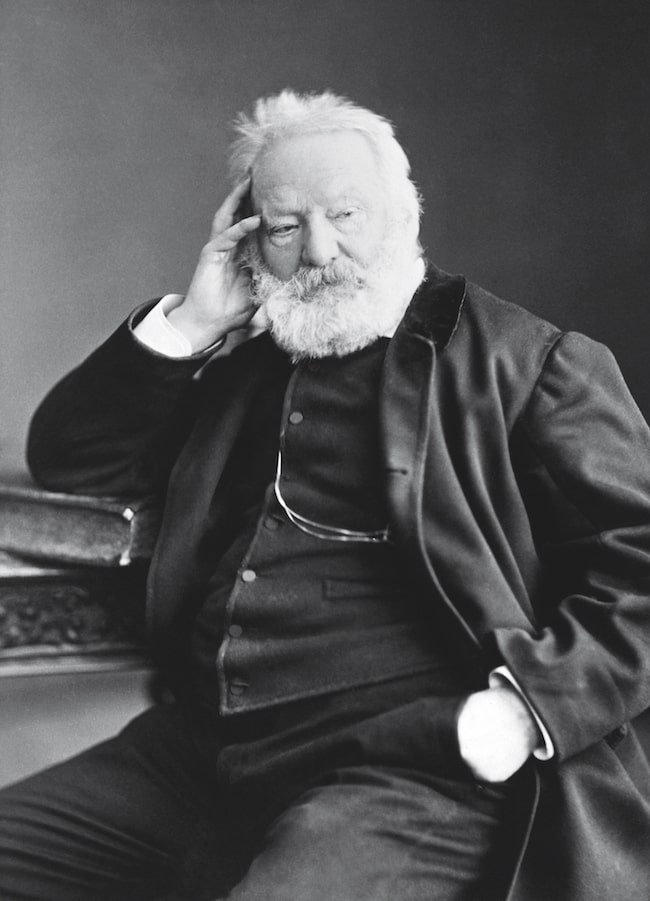

On the 135th anniversary of Victor Hugo’s death, Chloe Govan heads to Paris to relive the life-changing experiences that shaped one of the world’s most famous novels, Les Misérables

For those Francophiles who have seen or read Les Misérables, exploring author Victor Hugo’s former haunts in Paris might be the next logical step. The stories to be uncovered promise to reveal an unsettling truth about 19th-century life in the city – and they’re certainly not to be missed.

Perhaps one of the most heart-rending scenes of the novel, highlighting in harsh neon technicolor the divide between the privileged and the poor, is the one where a desperate and destitute man is sentenced to years of hard labour in jail merely for daring to snatch a loaf of bread to feed his sister’s starving children. The pitiful Jean Valjean’s clothes are torn, bloodied and covered in thick layers of mud when he commits the act, but no sympathy is forthcoming. He goes on to endure almost two decades of imprisonment and is ultimately rewarded for his subsequent virtuous living with little more than an undignified burial in an unmarked pauper’s grave. Valjean’s fate might sound like the consequences of living in an unfathomably cruel dictatorship, but in fact it is based on one of Hugo’s real-life experiences in Paris.

A room at the Hôtel du Petit Moulin. IMAGES © ALAMY, LEVALLOIS PERRET, ZAIRON, FRANCISCO ANZOLA

Tucked away in a quiet, secluded street away from the hustle and bustle of the city is an unassuming building now known as the Hôtel Du Petit Moulin. A luxurious residence boasting designs by Christian Lacroix and regal wallpaper adorned with crowns, its interior leaves very few clues as to its past, but in fact it was the very place where the Les Misérables author would come each morning to devour a freshly baked baguette. And, or so the story goes, it is also the location where he witnessed the arrest of a bread thief himself – an experience which prompted him to shape the character of Valjean.

Outside, the hotel still retains its original façade, spelling out the word ‘BOULANGERIE’ in vintage font, and therefore to the casual passer-by, it is no luxury hotel but an iconic symbol of vintage Parisian food shopping. Every now and then, a confused traveller will still stumble inside asking for bread – perhaps unsurprisingly, since its frontage still advertises classic French baguettes and Viennese seeded rolls.

That ill-fated morning, when Hugo witnessed the police cuff their victim – with merely seconds to spare before he fled the boulangerie – he spotted a duchess and her daughter looking coldly on, showing no sympathy for his plight. This, along with the haunting memory of the thief being led away, prompted him to put pen to paper for what was to become one of the most memorable scenes in his epic novel. He would sadly recall of the moment, “[He] was no longer a man in my eyes but the spectre of la misère, of poverty”.

Victor Hugo was a great campaigner for social change in his writing. IMAGES © ALAMY, LEVALLOIS PERRET, ZAIRON, FRANCISCO ANZOLA

In those days, of course, there were few things capable of showing social class more acutely than bread (or lack thereof). Not many years before Hugo’s birth, indignation over the exorbitant price of flour had sparked off the Bread Riots – and subsequently contributed to the start of the French Revolution. In 1789, one baker was even murdered on account of allegedly hiding loaves from the public. As one of King Louis XVI’s financial advisors gravely warned him, “Ne vous mêlez pas du pain!”.

Desperate Hunger

In Hugo’s day, with the fluffy white baguette not even in existence yet, there was a hierarchy of lower quality bread – and the poor were restricted to a hard, black loaf filled with unpalatable meal. In Les Misérables, Hugo depicts it as the type of bread that needed to be smashed open with an axe and soaked for 24 hours before it could even be eaten. To make matters worse, desperate hunger was so common among the very poor that it was not unheard of for victims to break their teeth trying to bite into it. Hugo would later be able to empathise thanks to his own experience of the unpalatable: during the 1870 siege by the Prussian army, he had resorted to eating (often unspecified) animals from the Paris Zoo. Always a vocal activist for the “paupers of Paris”, he believed that the legal and class systems were designed to trap workers and confine them to a life of perpetual poverty – and he used his magnum opus as a stark vehicle for his social message.

The Pavillon de la Reine, looking over Place des Vosges. IMAGES © ALAMY, LEVALLOIS PERRET, ZAIRON, FRANCISCO ANZOLA

No matter how many hours poor Fantine works as a seamstress, she cannot afford to pay for her basic needs. First she sells her hair, despite its withering from malnutrition, then she parts with her front teeth, before finally selling her body too. Yet even that does not release her from the endless cycle of debt and poverty.

She too was modelled on a real-life sex worker whom Hugo had “saved” from being arrested for assault. The streets where these events took place were not far from the former boulangerie.

The Church of Saint-Paul, which inspired the wedding scene between Cosette and Marius. IMAGES © ALAMY, SHUTTERSTOCK

For those who can afford to, a stay at the Hôtel Du Petit Moulin’s nearby sister residence, Pavillon de la Reine, might be a tempting option. The two hotels are within half a mile of each other in the heart of Hugo’s former neighbourhood. The latter, on the vibrant, tree-lined Place des Vosges, boasts a suite dedicated to him. Additionally, it is a mere two-minute walk from the Maison Victor Hugo, where the author wrote Les Misérables. Nowadays a free museum open from Tuesday to Sunday, no pilgrimage would be complete without a visit. Hugo’s descendants have recreated his bedroom as authentically as possible in the place where he died back in 1885, while visitors can view samples of his handwritten manuscripts, letters and even an original ink well that he used.

Elsewhere in the Marais district, the Church of Saint-Paul is worth a visit as the location that inspired the marriage scene between Cosette and Marius. Intriguingly, the venue also played host to a real-life wedding for one of Hugo’s nearest and dearest: his daughter Léopoldine. Those who are theatrically inclined will want to add La Comédie Française to their itinerary too. It is here that Hugo’s play, Hernani, was first performed in 1830, introducing the joys of Romanticism to a conservative crowd and challenging the societal norms of the time.

Legacy Lives On

The opulent interior of Le Grand Véfour. IMAGES © ALAMY, SHUTTERSTOCK

Further afield, another must-visit location is the opulent Grand Véfour restaurant, embellished with ballroom-style crystal-encrusted mirrors and sumptuous velvet seats. Intriguingly, while it might have been renowned as a place for the literati, it was also frequented by the more ‘rock ‘n’ roll’ stars of the era, such as the infamous Marquis de Sade. Close to the window table where Hugo always sat for his usual serving of vermicelli noodles, mutton and white beans is de Sade’s favourite table where he would bring a local lady of the night for typically French delicacies such as pigeon as a prelude to business. The idea of the pair mingling – a virtuous peace protestor and socialist versus an openly sadistic devil-may-care aristocrat – is amusingly incongruent, but fortunately they attended at slightly different eras in history: when the villainous Marquis de Sade drew his final breath in a mental asylum, Hugo was a mere 12-year-old schoolboy, learning his lessons.

Now, some 135 years after his death, Victor Hugo’s legacy lives on through one of the world’s bestselling books, and his fights for equality and for better conditions for the poorer echelons of society are believed to have helped spark radical reform over the years. Those willing to open the ‘Pandora’s Box’ of vintage Paris will be rewarded with an uncommon insight into a forgotten era. What are you waiting for? Grab yourself a copy of Les Misérables and hit the streets.

Read the ‘Les Misérables’ book review here.

Purchase your copy of the book here.

From France Today magazine

Victor Hugo’s daughter, Léopoldine. IMAGES © ALAMY, SHUTTERSTOCK

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in Hôtel Du Petit Moulin, Place des Vosges, Victor Hugo

By Chloe Govan

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *