Parisian Walkways: Faubourg Saint-Antoine, the Heart of Fine French Cabinet-Making

Every year, more than seven million people flock to the Palace of Versailles to behold the jaw-dropping luxury in which the French monarchy once resided. They stand wide-eyed before the towering frescoed ceilings; they marvel at the gilded wood panelling, the elaborately carved friezes and cornices; and perhaps above all, they gaze in wonder at the absolute extravagance of the furnishings.

Take Marie Antoinette’s standing jewel coffer by Martin Carlin, veneered with numerous precious woods – amaranth, sycamore, tulipwood, holly, ebony – and inlaid with 13 masterfully painted Sèvres porcelain plaques. Or the Hameau de Trianon writing desk by Jean-Henri Riesener, with its exquisite ornamentation of delicate flowers and frolicking cherubs in gold, reinstalled at Versailles in 2011 after a 217-year absence – at the cost of €6.75 million. And finally, the Bureau du Roi by Jean-François Oeben, Louis XV’s richly ornamented cylinder bureau, boasting intricate marquetry with a roll top system and locking mechanism of stunning ingenuity. A masterpiece of French cabinetmaking, requiring nine years to build, it’s considered one of the finest pieces of furniture ever made.

Faure at work in Ebénisterie Straure. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

But for all this artistry that the French monarchy fascinates us with, we forget that they never lifted a finger in the fabrication of such treasures. Their creators, men like Carlin, Riesener and Oeben, were not noblemen, but humble – if brilliant – craftsmen. And it certainly wasn’t in the stultifying and codified world of Versailles, with its rigid hierarchies and unremitting ceremony, that these craftsmen found the inspiration to create such works of art, to innovate so freely, to imagine chairs, commodes, clocks and desks the likes of which had never been seen before. In fact, these craftsmen lived and worked far from the palace, in an area then on the outskirts of Paris. An unconventional neighbourhood of such freedom and bustling vitality, it not only fostered revolutions in French cabinetmaking, it also gave birth to the actual Revolution: Faubourg Saint-Antoine.

Today, rue du Faubourg Saint-Antoine is a street beginning at Place de la Bastille, and continuing to Place de la Nation. But in the late 1700s, Faubourg Saint-Antoine was an agglomeration just outside the capital on the estate of Abbaye Saint-Antoine-des-Champs (today Hôpital Saint-Antoine), situated along one of the main roadways leading into Paris. (Faubourg is an ancient French term, from the Latin foris, ‘out of’, and burgum, ‘town’ or ‘fortress’.) For centuries, the neighbourhood had been associated with the trade of wood, historically brought up the Seine and unloaded on the quays nearby. But in 1657, a new era of exceptional privilege began when the king exempted the artisans of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine from the control of the Parisian craft-guilds. The rigid guild system, in place since the late Middle Ages, collected taxes for the king, dictated how and what trades craftsmen could practise, and even what materials they could use.

A furniture sign in Faubourg Saint-Antone. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

The king’s gift came as a veritable breath of freedom for the faubourg. Skilled craftsmen from across Europe flooded in. “These measures would be a boon to the entire furniture industry and all the artisans of the faubourg,” writes Jacques Hillairet, author of the Dictionnaire historique des rues de Paris. “They would allow the carpenters of Faubourg Saint-Antoine to embrace their creativity [and their curiosity for new styles, materials and techniques from around the world], to be inspired by furniture styles from China, to create furniture with exotic island woods, tortoiseshell inlays, ornamentation with brass fillets, veneers in walnut, cedar, ebony and every other kind of wood.”

A century later, the faubourg had become the largest furniture manufacturing centre in France, a place overrun by wealthy entrepreneurs, hard-working artisans, and masses of impoverished Parisians seeking factory work and charity from the abbey. “I don’t know how this faubourg survives,” wrote the 18th-century chronicler Sébastien Mercier. “Furniture is sold from one end to the other; and the poor population that live here have no furniture at all.” This unique mélange of poverty and opportunity proved a potent cocktail for the revolution to come.

Cour Damoye. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

In April 1789, a rumour circulated that Jean-Baptiste Réveillon, a luxury wallpaper manufacturer of Faubourg Saint-Antoine who furnished the noblesse, intended to lower his workers’ wages – at a time when many Parisians could barely afford bread. A riot resulted, with thousands of protesters looting Réveillon’s home and factory, until soldiers fired on the crowd, killing dozens. Today, historians consider the Réveillon riots the true beginning of the French Revolution, and the bloodiest journée until the great insurrection of August 1792. The people of Faubourg Saint-Antoine were on the front lines then as well, the seditious brewer Antoine Santerre having rallied the masses at his faubourg brewery (formerly at number 210), before taking command of the National Guard and storming the Tuileries Palace, which finally ended the monarchy.

Glorious reproduction furniture in the showroom of Dissidi. Photo: Dissidi

As Victor Hugo wrote in Les Misérables, “one can’t help but ponder Faubourg Saint-Antoine and the incredible stroke of fate that placed at the very gates of Paris this powder keg of hardship and ideas.” Today, several Paris companies plunge visitors into this world of unparalleled artistry and revolutionary fervor with historical walking tours. “The people of Faubourg Saint-Antoine were always on the front lines – in 1789, 1830, 1848, the Paris Commune – and it was these streets which allowed them to become the revolutionary people par excellence,” says Bernard Grave, co-founder of Un Jour de Plus à Paris, whose guided tours include a history walk through Bastille and Faubourg Saint-Antoine. “When you visit this neighbourhood, you realise it’s entirely made of little cours and passages. Which also explains why the people of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine were so difficult to repress – as soon as the royal guard or the police tried to arrest people, they could step through a courtyard, slip through a passageway, turn a corner, open a door, and disappear.”

To walk the faubourg and its atmospheric courtyards, passageways and impasses, is to find oneself face to face with the neighbourhood’s living history. For these cobblestone and vine-covered walkways – with evocative names like Cour Damoye, Cour de l’Étoile d’Or, Cour des Trois Frères, Cour de la Maison Brûlée, Passage de l’Homme, Cour de l’Ours, Passage de la Main d’Or – still bear traces of their rich pasts, from fountains and faded signs to sun dials. And though many furniture workshops have been replaced by architecture firms in recent decades due to soaring rents and the rise of mass-market manufacturers like IKEA, the passages are still occupied by some of the faubourg’s finest craftspeople. Some of these streets are privatised now, but on business days most are open to foot traffic, such as the Passage du Chantier, an ancient street long ago used as a chantier de bois or wood stockyard, where some of the last torchbearers of the faubourg’s furniture business ply their trade.

Ebénisterie Straure. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

Every year, during the Journées des Métiers d’Art when craftspeople open their workshops to the public, history lovers and aesthetes pour into one of Faubourg Saint-Antoine’s most quintessential ebénisteries, or cabinetmaking workshops – Atelier Straure. [Learn more here.] In the Cour de l’Ours, whose entrance is still marked by a bear sculpture left in the Middle Ages by the Abbey of Ourscamp, Pierre Strack and Philippe Faure restore antique furniture masterpieces while also creating new works, drawing on archives of original plans, moulds and models of furniture going back three centuries.

“We look at these styles today, and we can’t imagine that at one time, it was modern!” says Strack. “They transport us to another era, when the royalty set the fashion, published the canons of beauty, and when great upheavals in world history were taking place, like Napoleon’s return from Egypt, which caused a great revival of Egyptian style in the arts.”

A sculpture on the walls of Passage de la Main d’Or. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

On the wall hangs a copy of Marie Antoinette’s bed frame, which Straure used to create a bed for an ambassador’s residence in Paris. Such refined, intricately carved creations are typical of the team’s commissions. “We decided a long time ago, that the higher you rise in the pyramid of technique, the more work – and the less competition – you will have,” says Strack. As a result, Straure’s clientele today include some of the world’s greatest fortunes and decorators of palace hotels. Indeed, many faubourg craftsmen survive today thanks to the luxury world’s demand for increasingly rare savoir-faire.

“I may never step foot in the Hôtel Crillon,” says Jean Pouliquen of Atelier Marcotte, a historic bronze turning workshop in Passage de la Main d’Or – one of two remaining in France. “But if I walk by with my wife, I can always point to the door handles we made.”

Atelier Marcotte. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

Besides palace hotels, Pouliquen and his partner Maurice Favard also welcome the public, and collaborate with Straure and other faubourg cabinetmakers creating decorative brass elements for furniture, including exquisite handles and knobs for doors and drawers. So exquisite, the French state recently awarded Ateliers Marcotte the prestigious label Entreprise du Patrimoine Vivant.

Such recognition gives hope for the future to François Illy of Dissidi, artistic furniture makers since the 1900s in the Passage de la Bonne Graine. For without this surviving network of expert, interdependent craftsmen – bronze turners, gilders, French polishers, leather workers – the faubourg couldn’t remain the vibrant centre of high quality cabinetmaking it has. “There is spirit of the faubourg, which is very precious, and it’s something we and the few other establishments remaining must work to preserve today.” says Illy. “It’s the idea of a common heritage, a shared story, that of having written here, in this neighbourhood, the most beautiful pages in the history of French cabinetmaking.”

Dissidi, artistic furniture makers since the 1900s. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

Walking through Dissidi’s showroom, past the museum-quality copies of Louis XV and XI-style masterpieces they’ve created, that history comes to life. Illy points to a Louis XVI-style table. “Imagine, the original of this table was created in the 1780s by Martin Carlin, a favourite cabinetmaker of Marie Antoinette, in a workshop 200 metres from where we stand.” The French monarchy may be long gone, but as a visit to Faubourg Saint-Antoine confirms, France’s noblest traditions of craftsmanship are alive and well.

BOUTIQUES AND RESTAURANTS

Ebénisterie Straure: 95 rue du Faubourg Saint Antoine, Tel. +33 (0)1 43 47 20 50

Tucked away up a charming Faubourg Saint-Antoine passageway, Straure is perhaps the neighbourhood’s most quintessential remaining ebénisterie or cabinetmaking workshop. Since 1984, Pierre Strack and Philippe Faure have earned a reputation for quality and craftsmanship, whether for contemporary furniture commissions or restorations of antique masterpieces.

This sign in the Passage de l’Homme provides a clue as to the proprietor’s vocation. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

Dissidi, 16 passage de la Bonne Graine, Tel. +33 (0)1 47 00 47 95

To visit Dissidi’s showroom, with its stunning chests, cabinets, chairs, sofas and tables, is to stroll through French furniture history. For three generations, the Dissidi family has specialised in the restoration and reproduction of antique wood furniture and panelling, be it Louis XV, XVI, Empire or Art Deco in style. Desire a museum-quality copy of Marie Antoinette’s desk? Look no further.

Ateliers Marcotte, 15 passage de la Main d’Or, Tel. +33 (0)1 47 00 25 72

Since 1996, Jean Pouliquen and Maurice Favard have perpetuated a tradition all but forgotten in France – bronze turning. These skilled artisans often work for palace hotels, restoring and creating chandeliers, bouillotte table lamps, candleholders, exquisite door knobs and drawer handles. Fortunately, they still sell to the public too, receiving clients at their 1934 workshop.

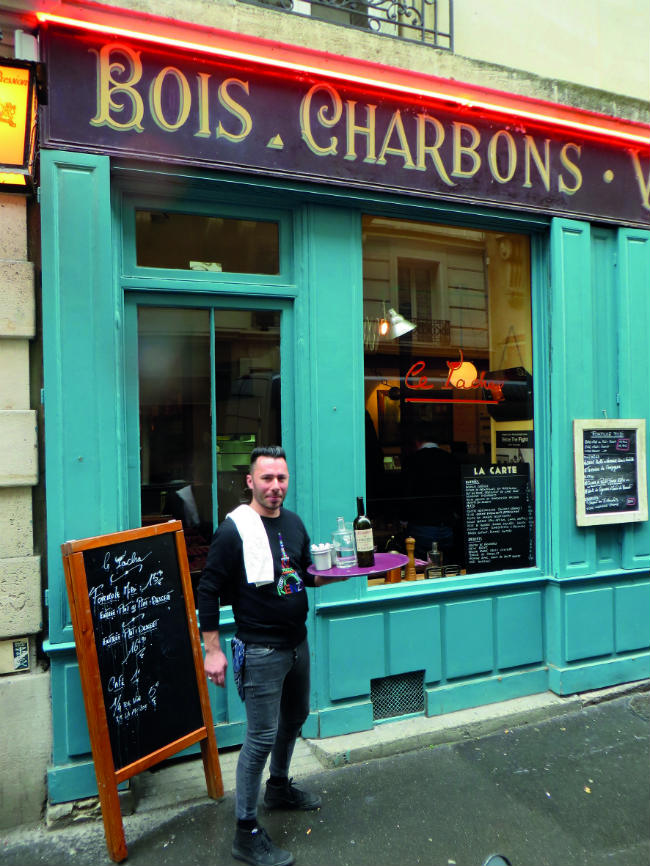

Le Pacha bistro. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

Le Pacha, 8 rue de la Main d’Or, Tel. +33 (0)1 48 05 37 17

The sign above this characterful bistro is a vestige of a particular type of café that once flourished in this quarter – the café-charbon. Here, hardworking Parisians once bought wood and coal to heat their homes, while also enjoying a glass of wine or an anisette. Today, it’s a bastion of classic bistro fare, good humour, and perhaps the best frog legs in Paris – oui, oui!

Emery & Cie, 18 passage de la Main d’Or, Tel. +33 (0)1 44 87 02 02

Hidden up a narrow side street, far from the bustle of Faubourg Saint-Antoine, Emery & Cie represents a different philosophy of the decorative arts. Removed from the ceaseless cycle of changing fashions, here styles are perennial, and what lends value to their stunning embroidered fabrics, rich wallpapers, and vibrantly coloured tiles and furniture, is the quality of workmanship.

Emery & Cie. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

Jouvence, 172 bis rue du Faubourg Saint Antoine, Tel. +33 (0)1 56 58 04 73

Chef Romain Thibault named his enchanting restaurant well. In French, Jouvence brings to mind la fontaine de jouvence – the fountain of youth – and there is something eternal about this former circa-1900 apothecary shop. From its impeccably preserved period décor, to its elegantly revisited French dishes and desserts, to its fresh-faced staff, Jouvence is a slice of Paris where time stands still.

From France Today magazine

Jouvence restaurant. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY