Christian Dior: In Memory of the New Look

His parents disapproved of his career choice. The Second World War interrupted it. And the crowds bayed for blood when he revealed his New Look. Chloe Govan reveals Christian Dior’s roller-coaster ride to success

“As long as Hitler controls Paris,” declared one American journalist, “Paris will never control fashion.” Taking these words to heart, Christian Dior, then in his 30s, set about waging a war of his own, and as the tanks and fighter jets of the 1940s loomed around him, the designer formed his own résistance against aesthetic oppression.

Even Dior’s tailoring showed off the female figure. Photo: Alamy, courtesy of Christian Dior Museum

Two years after the Germans surrendered the French capital, he launched what would become one of the most successful couture fashion brands in the world.

Dior was born in 1905 in the sleepy yet chic seaside town of Granville, Normandy. By the age of five, his affluent family had moved to Paris, hoping he would grow up to become a diplomat. Yet years later, after reluctantly studying for a degree in political science, the stifled creative rebelled.

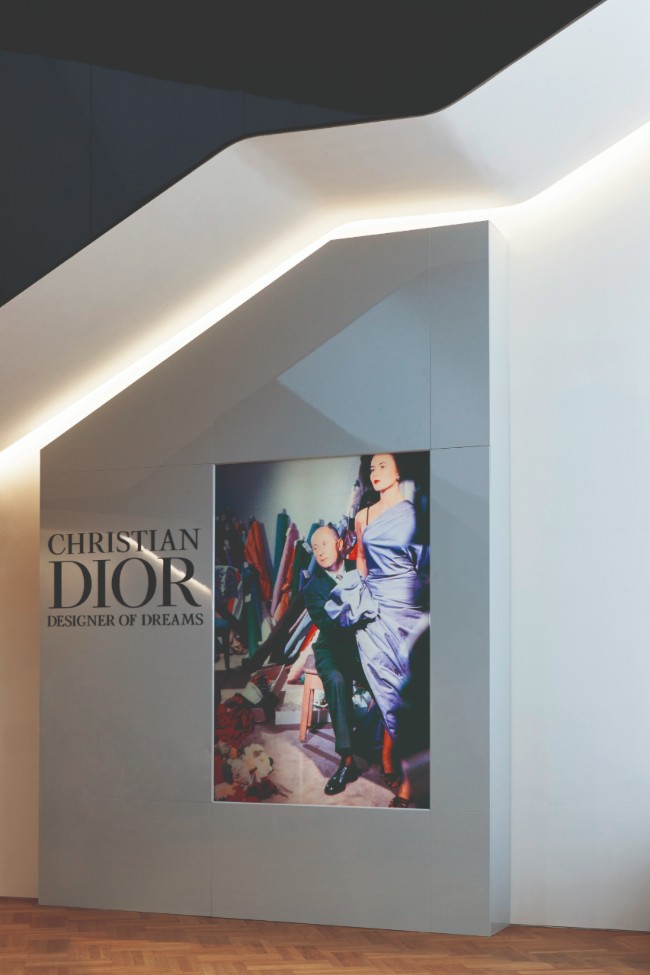

The ‘Dior, Designer of Dreams’ exhibition at the V&A Museum. Photo: Adrien Dirand

Dior’s parents were incandescent with shame when he opened his own art gallery – the first step on a multi-million franc career ladder

– believing that it would permanently tarnish the family name. Unapologetic homophobes, the Diors were embarrassed by his association with “effeminate” pursuits – indeed, they had banned him from studying architecture at university for this very reason. The fact that soon-to-be world-renowned artists such as Salvador Dalí and Joan Miró were exhibiting at the gallery, or that Pablo Picasso’s studio was right next door, meant little to his horrified parents. To them, his choice of career represented a world of casual hedonism and illicit homosexuality. Curiously, for a family that had made its name in the less-than-glamorous fertiliser industry, they seemed to believe it was art that would blight their reputation. They agreed to finance their errant son on the strict condition that the Dior name be kept hidden.

Christian Dior with model Sylvie, circa 1948. Courtesy of Christian Dior Museum

But young Christian would have far more to contend with and overcome than his controlling parents’ purse-strings; namely the choke-hold of the Great Depression and the Second World War. He was forced to sacrifice his gallery and the short stint of employment that followed with fashion designer Robert Piguet was cut short when he was called upon to serve in the military.

NEW CONTROVERSY

The war over, in 1947 the world started to sit up and take notice of Dior’s debut solo launch – the now-legendary New Look. The collection was all about creating a curvaceous silhouette – prominent shoulder pads, moulded busts and voluminous, bouffant skirts, all anchored by a shapely cinched waist. Formerly elegant French women, emaciated in the aftermath of the war and still feeling the after-effects of food rationing, were desperate to regain their curves. It seemed the exaggerated femininity of Dior’s collection had come along at just the right time – although not everyone agreed.

The ‘Dior, Designer of Dreams’ exhibition at the V&A Museum, the Garden Section. Photo: Adrien Dirand

Some were enraged by the sheer amount of fabric used in his circle skirts – considered a shameful waste by those who’d previously scrimped and saved during wartime austerity. Others simply found the designs horrifyingly impractical. From lung-squeezing corsets to skirts so weighty that the women who sported them could barely fit through doorways, they were regarded by many as the “absolute antithesis of feminism”.

And why, a quizzical Coco Chanel asked, would anyone take style advice from a man “who doesn’t know women [but merely] dreams of being one”?

The ‘Dior, Designer of Dreams’ exhibition at the V&A Museum, Designers for Dior section. Photo: Adrien Dirand

But while fellow designers simply sneered or raised their perfectly arched eyebrows in amusement, the public’s reaction was much more dramatic – and chaos quickly descended, both on and off the catwalk. In Montmartre, just a few days after the collection’s launch, sales assistants physically assaulted the models, attempting to tear their designer dresses from their bodies and rip them to shreds.

Protesters around the world stormed fashion shows brandishing placards that read, “Burn Dior!” and, “Mr Dior, we abhor dresses to the floor!”. It seemed even his own industry had turned against him. Elle published a feature highlighting the cost of Dior’s dresses and pointing out what could be bought for the same price – such as 789,000kg of meat. Other magazines commented that post-war women would rather eat than buy frivolous fashion. Regardless, Dior’s supporters were just as passionate as his detractors. They considered his designs a celebration of liberty.

The ‘Dior, Designer of Dreams’ exhibition at the V&A Museum. Photo: Adrien Dirand

ROYAL APPROVAL

For Dior’s fans, the New Look represented a return to extravagance and luxury in an era of ration cards and meagre clothing coupons. In wartime, many women had been driving tractors and working the fields as land girls, or running busy households alone with a toddler under each arm, so the chance to dress glamorously was rare, if not non-existent. Dior’s clothing was far from just a style – it formed part of a political revolution.

Gone were the days of austerity and self-denial and no longer would women be afraid to reach into their hand-me-down purses. Now the only thing that was restrictive was the waistline – and that was exactly how Dior and his customers wanted it.

Princess Margaret in the Dior gown she wore on her 21st birthday. Photo: Popperfoto/ Getty Images

In the midst of all the controversy, Dior won the support of Princess Margaret, who wore one of his designs for her 21st birthday party. She was photographed in the extraordinarily bouffant gown, earning him abundant positive publicity. While the likes of Marie Antoinette before her supposedly declared “Let them eat cake!”, Margaret was now flaunting the designer’s reckless use of fabric with the implicit cry of “Let them wear couture!”. That year, no fashion photo could match it in the controversy stakes.

Defiantly, Dior continued to create designs that emphasised the differences in body shape between women and men. Hips were padded in the same way that a modern-day brand might pad a bra. The exaggerated hip-waist ratio that he forged helped sustain a feminine appearance, even for women wearing suits. Posters soon appeared emblazoned with witty repartee such as “Do my hips look big in this?” as a nod to the Dior style.

Princess Margaret presents Dior with a scroll entitling him to Honorary Life Membership of the British Red Cross. Photo: Popperfoto/ Getty Images

MOVING WITH THE TIMES

The fashion house was soon bringing in millions of francs a year and its glamorous gowns were responsible for more than half the country’s haute-couture exports, as well as half of France’s total exports to the USA. It had also diversified, adding furs, perfumes and stockings to its repertoire.

The latter were especially significant for post-war liberation. Those seeking the New Look had previously had to make do with staining their legs brown and painting a line down the back to mimic the effect of seamed stockings. Thanks to Dior, these painstaking efforts could be abandoned in favour of the real article.

Christian Dior’s house and museum in Granville, where he spent his early years. Photo: Shutterstock

However, a decade after the launch of the New Look, tragedy struck – Dior died of a heart attack aged just 52. Rumours circulated that it had been prompted by choking on a fish bone, by strenuous sex or had happened after a game of cards. To this day, the truth is unknown. What is indisputable is that the fashion world went into mourning, with thousands attending his funeral. Among them was his friend Pierre Bergé, who said: “It was a national event. It was as if France had ceased to live.”

With the death of Dior came the demise of the styles that had made him famous. Some had been practical enough for everyday living, such as the elegant Bar Suit, comprising a jacket with a contrasting corseted waist and peplum hem and a sensible yet chic long A-line skirt.

The ‘Dior, Designer of Dreams’ exhibition at the V&A Museum, Dior in Britain section. Photo: Adrien Dirand

However, the more extreme designs had been downright passion killers. The most extravagant included boned evening dresses that apparently “flared out as much as two feet in all directions”, forcing party-going couples to dance at arms’ length. It was difficult to sit down and impossible to order a drink from a crowded bar.

One bemused buyer joked that while these outfits were well-suited to royalty or silver-screen stars on photoshoots, they were “totally useless for any woman who wants to do anything!”.

Clearly, the brand had to modernise. Women no longer needed lavish clothes that they struggled to move in as a means of bragging about their post-austerity wealth and freedom. Now they wanted liberation of a different kind – and demanded that it come in the shape of the lightweight, less restrictive mini-skirt.

The ‘Dior, Designer of Dreams’ exhibition at the V&A Museum, Atelier section. Photo: Adrien Dirand

By the 1960s, the protesters were back on the streets but this time it wasn’t because the Maison Dior was too extravagant – it was because the long skirts were too conservative. In the UK, for example, a group called the British Society for the Protection of Mini Skirts organised marches outside fashion shows – and the house of Dior duly granted their wishes for younger, edgier outfits. While the fashionistas of the 1940s believed that, paradoxically, their clothing had given them freedom by confining them, the women of the 1960s sought a rather more sexual revolution.

Even to this day, Dior’s original message of female liberation is fiercely upheld, albeit in new ways: current creative director Maria Grazia Chiuri champions T-shirts emblazoned with the slogan “We should all be feminists”. So despite controversial beginnings, it seems certain that Christian Dior’s legacy will live forever. His parents would have been proud…

From France Today magazine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in Christian Dior

By Chloe Govan

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY