On the Trail of the Marquis de Lafayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, the Marquis de La Fayette (1757 – 1834), was an American hero. Orphaned early in life, Lafayette joined the French Royal Army in 1771. After having achieved the rank of general in 1776 at only 19 years of age, he became inspired by stories of the American colonists’ struggles against British oppression and sailed across the Atlantic to join the uprising.

Lafayette was shot in the leg at the Battle of Brandywine and spent the difficult winter in Valley Forge with Washington. The two became quite close and Washington began to refer to him as “my adopted son.” In May 1778, Lafayette eluded capture by the British and successfully led American troops in defending Monmouth Courthouse in New Jersey from attack.

By 1779, the Americans desperately needed more money and arms. Lafayette sailed back to France to persuade King Louis XVI to offer more help. When he returned with both money and arms in 1780, Washington gave him command of the Virginia Regiment of the Continental Army. In 1781, Lafayette laid siege to the British at Yorktown until Washington arrived with additional troops. General Cornwallis was trapped and forced to surrender, thus ending the war.

After the war, Lafayette returned to his estate, Château de la Grange-Bléneau, in Courpalay, Seine-et-Marne where he lived until his death in 1834.

Aerial photograph of Castle Clinton in Battery Park (New York City), Castle Clinton National Monument

Americans never forgot Lafayette. In 1824, President Monroe invited him to revisit the United States in anticipation of the 50th anniversary of the Revolution. Accompanied by his son, Georges Washington de Lafayette, Lafayette arrived at Castle Clinton on the Battery in Manhattan on August 15, 1824. He was greeted by a military escort which accompanied him to City Hall. Their route was lined by over 50,000 people (a third of the city’s population). In his journal, Lafayette’s personal secretary, Levasseur, described the parade:

The general, attended by a numerous and brilliant staff, marched along the front; as he advanced, each corps presented arms and saluted him with its colours; all were decorated with a riband bearing his portrait. During this review, the cannon thundered from the shore, in the forts, and from all the vessels of war. At the extremity of the line of troops, elegant carriages were in waiting. General Lafayette was seated in a car drawn by four white horses, and in the midst of an immense crowd, we went to the City Hall. On our way, all the streets were decorated with flags and drapery, and from all the windows flowers and wreathes were showered upon the general.

For the next year, Lafayette then toured the United States, travelling to each of the 24 states. He attended the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Bunker Hill, revisited Brandywine battlefield in Pennsylvania, met with former officers and soldiers in his regiment and paid his respects at the graves of George and Martha Washington at Mount Vernon.

Lafayette statue in Union Square. © Fern Nesson

Wherever he went, Lafayette was greeted with an extraordinary outpouring of patriotic emotion. The timing of his visit could not have been better. The presidential election of 1824 had just ended with Andrew Jackson winning the popular vote but the House of Representatives giving the victory to John Quincy Adams. Party politics and sectionalism were dividing the country, endangering the spirit of unity evinced by the Revolution.

Lafayette was the last living general of the Revolutionary era, a throwback to better times, a reminder of our revolutionary ideals, a figure whom all could celebrate. He was welcomed across our country with parades, cheering crowds, bands, cannonades. At Bunker Hill in Boston, Daniel Webster declared that Lafayette was “the man who spread the electric spark of liberty to the world.”

Lafayette returned to New York in July 1825. In Brooklyn, he was asked to dedicate the Children’s Library (predecessor of the Brooklyn Museum). At the dedication, he was surrounded by young children and he lifted up one small boy so that he could watch the ceremony. That boy was the six-year-old Walt Whitman.

On the evening that Lafayette set sail for France, 40,000 people gathered at Castle Clinton to see him depart. After a fireworks display, Lafayette cut the anchor cables to The American Star, a hot-air balloon. Its pilot Eugene Robinson tossed American and French flags to the crowd below as Lafayette’s boat pulled away from the wharf. Levasseur reported that “profound dejection was imprinted on every face and, although the wharfs were covered with a huge crowd, a solemn silence alone reigned.”

Lafayette by Bartholdi in Union Square, New York City. © Fern Nesson

In honour of Lafayette’s visit, New Yorkers named Lafayette Square in Morningside Heights, Lafayette Street in NOHO, and Lafayette Avenue in Brooklyn after him. And, in 1876, on the 100th anniversary of the American Revolution, the French donated a statue of him on horseback to New York City. Fashioned by Bartholdi, the same sculptor who made the Statue of Liberty 10 years later, New York placed it at the entrance to Manhattan’s newest park, Union Square.

New Yorkers were not the only Americans to honour Lafayette. Cities were named after him in Pennsylvania, Louisiana, Indiana, California, North Carolina and Colorado. Lafayette (or Fayette) counties can be found in Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Tennessee, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Arkansas, Mississippi, Florida, and Louisiana. Lafayette Squares anchor the downtowns of Washington D.C. and New Orleans and countless streets bear his name throughout our country.

Equally prevalent are statues of Lafayette by renowned sculptors, both French and American. Jean-Antoine Houdon, Bartholdi and Daniel Chester French each contributed statues of Lafayette to Richmond, Virginia; Tulsa, Oklahoma; Easton, Pennsylvania and Prospect Park in Brooklyn. Statues and monuments have often become the subject of controversy in our country but Lafayette’s likenesses have never raised any issues. He was and continues to be revered, no matter the political climate of the times.

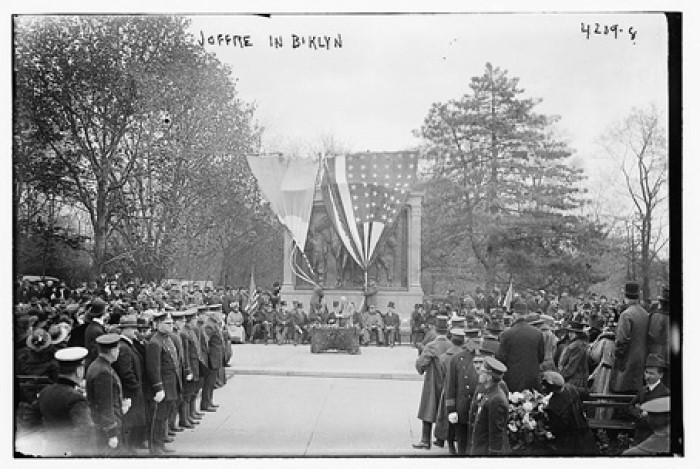

Dedication of Lafayette Monument in Prospect Park Brooklyn, 1917

When General Pershing and his U.S. troops arrived in Paris to fight in World War I, one of his first stops, on July 4, 1917, was a visit to Lafayette’s grave. Standing at the gravesite in Picpus Cemetery, Pershing’s aide, Colonel Stanton, declared “Lafayette, we are here.” Pershing then placed a United States flag at the site.

Lafayette’s Grave, Paris. Public domain

Even many years later, Lafayette’s contributions have not been forgotten. Every year on July 4, the flag on Lafayette’s grave is replaced with a fresh one in a joint French-American ceremony. And in 2002, Congress granted Lafayette honourary U.S. citizenship and yet another extraordinary event took place more recently. In 1780, Lafayette sailed from France to the U.S. on the French ship L’Hermione. Lafayette rejoined the fight in Virginia; L’Hermione also joined the war, doing battle against the English in Chesapeake Bay.

L’Hermione replica in Rochefort, France. Public domain

In 1997, the French people raised $27 million dollars to build a replica of L’Hermione in Rochefort, France, the same shipyard in which the original was built. Finished in 2015, L’Hermione redux set sail in April 2015 for a 27-day trip across the Atlantic. She arrived in Yorktown, Virginia, and later that summer visited Annapolis, Boston, Philadelphia and New York City.

At the launch, French President Hollande said, “The Hermione is a luminous episode of our history. She is a champion of universal values, freedom, courage and of the friendship between France and the United States.” President Obama wrote in a letter of congratulations: “France is our nation’s oldest ally. For more than two centuries, the United States, Lafayette and France have stood united in the freedom we owe to one another.”

Lafayette is truly a hero for the ages.

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in 18th century, French history, history, monuments

By Fern Nesson

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY