George Sand: The Radical and Revolutionary Female Writer of France

Feminist before her time, user of non-binary pronouns more than 150 years earlier than today, George Sand was a prolific writer and produced some of her finest work from her house in Nohant.

The Berry countryside north of the Creuse is rich in flamboyant Gothic and Renaissance châteaux. Here, amongst its wooded hills and beautiful valleys, the late 18th century manor house, Nohant, sits like a grand lady in its leafy, secluded gardens waiting to receive and entertain her visitors offering a vignette of a past era, an insight into the lives of vaguely familiar people. The voices of some of the greatest artistic, literary and musical minds of the time reverberate everywhere, all guests, visitors or lovers of the most prolific woman writer in the history of literature. She nurtured their minds with the same care as she nurtured her gardens. Without them, Nohant would be no more than any other beautiful symbol of a bygone time.

When the novelist Virginia Woolf claimed that a woman must have money and a room of her own if she was to write fiction, she was decrying how women writing in a patriarchal society were viewed as anti-social feminists. Yet almost a century earlier, the first solo novel Indiana by George Sand, was being published to great acclaim. In the 1830s and 1840s in England, in her lifetime she was more famous than Victor Hugo or Honoré de Balzac, influencing writers and thinkers of the time. The novel was written in her first ‘room’, her boudoir in Nohant, the Berry chateau left to her by her grandmother, a notable free-thinker of her time. George Sand was to become not only a novelist and memoirist but also a strong political activist who fought for the rights of women.

George Sand

Born Amantine Lucille Aurore Dupont, George Sand has been compared with George Eliot who also wrote under a male pseudonym. They both wrote of weak, dishonest men who somehow managed to seduce women, but whereas Eliot wrote with her head, and wrote just five novels in her lifetime, Sand wrote passionately and spontaneously from her heart, producing eighty novels. In later years, she said that life resembles a novel far more than a novel resembles life.

Her own tumultuous family history resounding with passion, romance and betrayal, personal and political revolution, but above all, of resilience and determination, is the stuff of romantic, historical novels, that could have come from the pens of Antonia Fraser or Kate Mosse. Her intriguing story is as much about her involvement in violent, political revolutions as it is about her passionate love affairs with renowned artists, writers and musicians of the time. Equally important is the influence she had on their works and the high regard in which she was held.

She spent her childhood with her grandmother at Nohant where her tutor Deschartres, gave her an education very few girls received, introducing her to the works of many French and English philosophers, writers and moralists. They included Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose works greatly influenced her writing. Dressed in boys’ clothes, the young Aurore spent her days playing with local children, who told her stories of the beasts and ghosts of the countryside. She became enthralled with the magic of nature, her education and childhood experiences later finding expression in her lifestyle and works.

The Nohant manorhouse © shutterstock

A room of her own

George Sand found her room both literally and metaphorically when she escaped her suffocating marriage. In 1831, after negotiating a separation, relinquishing her estate and children to her husband, she went to Paris to live in a small flat with her lover, Jules Sandau. For now, she was free from the social restrictions of marriage, exploring the idea of free love with Sandau.

When the affair ended, she would discover other ‘rooms’ including an apartment in Venice where she lived for a year in a tempestuous on-off relationship with Alfred de Musset, and a Monastery in Mallorca with the composer Chopin. Her rebellious spirit embraced the soul of Paris, a city which had just had a revolution and she intended to use her freedom to its fullest advantage. She began to write articles for Le Figaro and to move in artistic and literary circles and soon became recognized as a central figure in the French Romantic Literary movement.

A portrait of a radical, revolutionary writer begins to emerge who would challenge the social norms that entrapped women in specific gender roles and lifestyles. In her daily life she dressed in men’s clothes, continuing a habit from her youth when, as a young girl, village women would close windows to prevent their children watching her, dressed in trousers and long coat, sitting astride her horse. Paris was acquiring its own ‘Gentleman Jack’ in George Sand, although rumors of Sand’s unproven scandalous affair with the actress Marie Dorval had not yet surfaced. Openly smoking in public, dressed as a man, George Sand was able to explore the cultural and artistic hotspots of this intellectually, stimulating city, which otherwise would have been closed to her.

In her novels she expressed an extremely modern concept of gender, redefining ideas of masculinity and femininity. She anticipated LGBTQ+ ideas of gender fluidity and reflected gender ambiguity in her writing by using masculine pronouns to describe her own experiences in masculine terms. Her friends and peers also alternated between female and masculine adjectives and pronouns when referring to her and she is described by one as the ‘king’ of novelists.

George Sand, portraits by Nadar

In 1837, Sand’s friend and past lover, the lawyer Michel de Bourges, helped her to regain her estate and she moved back there with Chopin, where they spent eight years together, during which time he composed some of his best work. Bourges greatly admired her strength of character, convincing her to speak out and reflect her feminist and political concerns in her writing and she went on to launch a literary review, two local papers and two national republican journals, becoming a member of the Provisional Government in 1848. Her final years were spent at Nohant with the sculptor, Alexandre Manceau, who encouraged her to buy a small cottage in the Indre village of Gargilesse. Here in ‘a room of her own,’ she wrote prolifically to support her generous lifestyle and her family, producing some of her finest pastoral novels.

She loved entertaining and made Nohant a social and cultural haven for some of the greatest creative minds of the time. It is impossible to escape her presence and if you listen very carefully, echoes of the animated voices of Balzac, Flaubert, Alexandre Dumas’ son, Franz Liszt, Delacroix, and Flaubert with whom she remained close friends until her death, beckon us from the past to discuss society, politics and perhaps, the latest scandal. A quiet stroll through the gardens of Nohant is interrupted by the echoing laughter of her children as Chopin, riding a donkey, joins in with their games. Writer, journalist, political activist, would-be anarchist, painter, dressmaker, theatre maker, botanist, entomologist – it is impossible to escape the presence of this multifaceted woman.

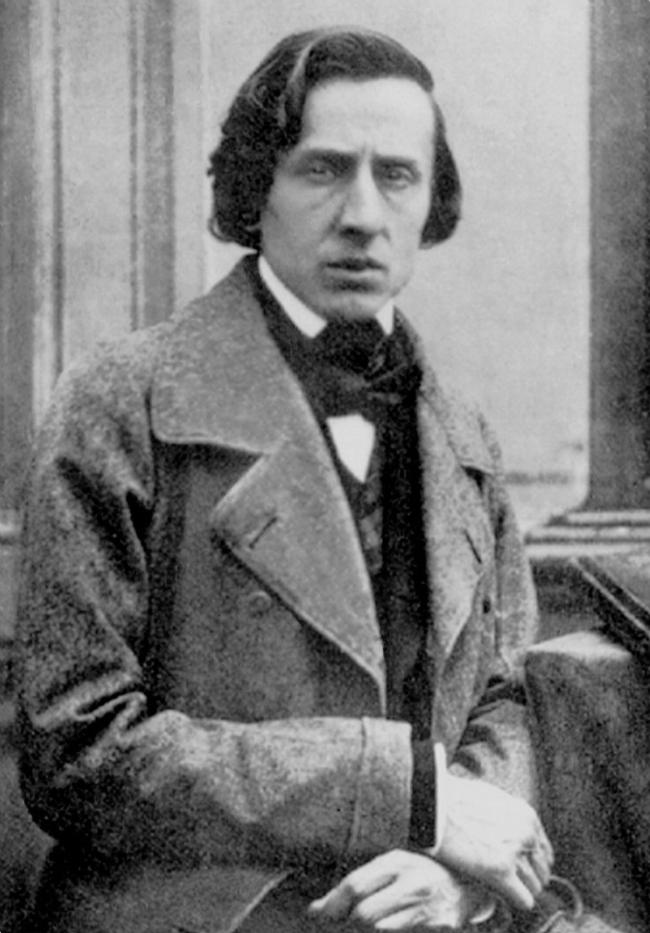

Frédéric Chopin

In a life far removed from that of a nun which her grandmother had once feared she would follow, she openly defied moral and social standards. Sadly, her flamboyant lifestyle eclipsed any serious critical evaluation of her literary works. After her death in 1876, Sand’s critics succeeded in diminishing her accomplishment and her literary popularity declined. Since the 1950s, there has been a revival of her work establishing her as a leading light for the feminist movement.

“The world will know and understand me someday,” Sand once wrote to her critics. “But if that day does not arrive, it does not greatly matter. I shall have opened the way for other women.”

Lead photo credit : George Sand, by Nadar, 1864

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in feminism, French authors, French icon, french literature, writer

By Anne Price

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *