In the Footsteps of Haussmann

Georges-Eugène Haussmann is credited with inventing Paris, revamping its boulevards and parks to create the city we know and love today.

“I passed the square of Les Halles, then open to the sky, through a number of red umbrellas of the fishmongers; then Rue des Lavandières, Saint-Honoré and Saint-Denis. The Place du Châtelet was quite wretched at this time… I crossed the old Pont-au-Change, which later I had to have rebuilt, lowered and widened, then followed the line of the former Palace of Justice, on my left the sorry huddle of low dives that then dishonoured the Île de la Cité, which I would have the joy of razing completely – a haunt of thieves and murderers… Continuing my route by the Pont Saint-Michel I had to cross the poor little square that the waters of Rues de la Harpe, de la Huchette, Saint-André-des- Arts and de l’Hirondelle all spilled into, like a drain.”

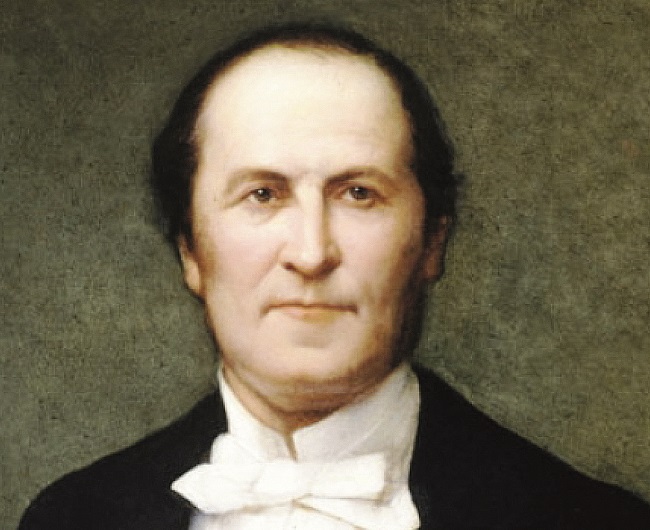

The footsteps that Georges-Eugène Haussmann took as a young law student would have a profound effect on the footsteps Parisians were to take for the next 170 years. As Napoleon III’s Prefect of the Seine, Haussmann transformed Paris, demolishing its ancient character in favour of a modern, clean one. Born in 1809 at his family’s townhouse at 55, rue du Faubourg-du-Roule, Haussmann was a sickly little boy who spent his early years with his grandparents in Colmar in Alsace. His frailty led to an obsession with cleanliness that would later manifest itself in his civic works.

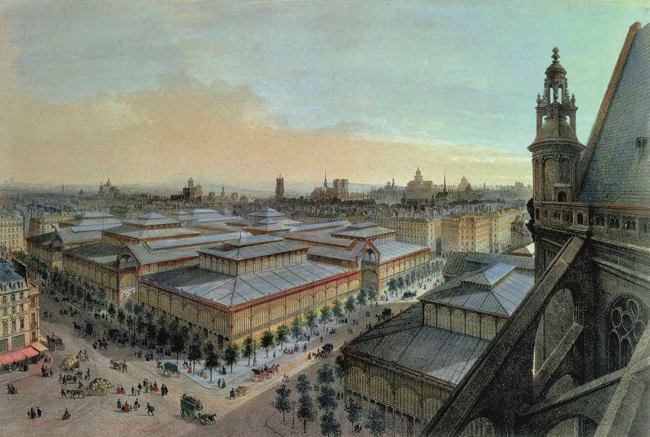

Les Halles © Wikimedia Commons

A prized préfecture

His grandfather had been a general in Napoleon Bonaparte’s army, and Haussmann claimed he himself had been a Bonapartist from the cradle. While strolling in the Tuileries with his much-adored grandpa, a five-year-old Haussmann, dressed in a miniature regimental uniform, spied his hero, Napoleon, and saluted him, crying out, “Long live the Emperor!”.

At eight, Haussmann attended an elite private school near Sceaux, a banlieue south of Paris and then, at 11, he was enrolled at the Lycée Henri IV, next to the Panthéon, known as the most challenging school in Paris. The naturally inquisitive Haussmann quickly rose to the head of the class. Thirsty for knowledge, he said: “One can cram a great many things into a schedule beginning at 6am and lasting to midnight and beyond.”

He studied music at the Paris Conservatory, and Haussmann’s characteristic quest for order was evident in his musical choices: every sonata was to have three well-balanced movements; every symphony four. He preferred the reliable works of Bach, Handel and Haydn over the free, Romantic works of his fellow student, Berlioz.

Now a sturdy and broad-shouldered 6ft 2in, the route Haussmann used to walk from the Church of Saint-Augustine (which is still there today) to his class at the Faculty of Law of Paris on the Place du Panthéon was a walk through time; from medieval squalor to 18th-century order. Paris’s meandering streets and old buildings held no charm for him, they just added to his abhorrence of disorder.

Haussmann presents his plans for Paris © Wikimedia Commons

Haussmann fought in these streets during the July Revolution. For six days and nights, he battled without rest, even capturing one of the Royal Guard. In recognition of his valour he requested a position in the French civil service, rejecting the military path favoured by his family. Haussmann was given the position of secretary general of the prefecture of Vienne in spring 1831.

For almost two decades Haussmann held sub-prefecture positions, from Poitiers to Bordeaux. He was an able administrator, but despite his diligence, his career moved laterally – rumours of his arrogance preceded him. Haussmann became entrenched in workaday civic concerns – a desperately needed road system in Nérac, a clock tower in need of repair in Saint-Girons… In the Gironde, he not only improved the schools and streets, but made inroads with the bourgeoisie. He married Bordeaux native Louise-Octavie de Laharpe in 1838 and they had two daughters, Marie-Henriette and Fanny-Valentine.

Rue Tirechape off rue de Rivoli circa 1853-70 © Wikimedia Commons

Haussmann’s fortunes continued to improve. He vociferously supported Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, nephew of the Emperor, as the presidential candidate for France. In 1848, when Louis-Napoléon was invested as the country’s first elected president, he promoted his ally Haussmann to the post of Prefect of the Var. Haussmann took on a more political role, redrawing electoral subdivisions in southern towns such as Cannes. He repeated the same task in the Burgundian department of Yonne. As Prefect, Haussmann, returned to Bordeaux in 1851. The house he and Octavie built in Cestas is today known as the Château Haussmann.

True to family tradition, Louis-Napoléon seized power in 1851, and it wasn’t long before he offered Haussmann the chance of a lifetime. On June 23, 1853, Napoleon III, as he was now known, picked Haussmann to run the most prized prefecture in the country – the Seine. He could ask for no more and, bedecked in a uniform encrusted with blue and silver, he was sworn in.

The administration saw Haussmann as “a tall, tigerish animal”, one who was wily, resourceful, audacious and brutally cynical. Ferocity was needed to deal with the backlash Napoleon III’s plans would have. At their first meeting, the monarch flourished a large map of Paris, crisscrossed with colourful lines demonstrating what he wanted to be built and what he wanted to be gone.

Château Haussmann © Wikimedia Commons

The radical reshaping of Paris rested on the questions of defence and hygiene. Not only were chaotic and winding streets easily barricaded during the frequent civil insurrections but they were a hindrance to Haussmann’s goal of improving the circulation of goods, people, water and sewage. Some of Paris’s historic quarters, malingering as insalubrious slums, were destroyed. Haussmann jokingly called himself “the demolition artist”, and among the staggering 20,000 buildings he dispassionately demolished, was his family home. His own lush apartment at 12 rue Boissy d’Anglas now too is gone.

The urban makeover evicted more than 100,000 Parisians but employed one fifth of the city’s workforce. For an unfathomable 17 years, Parisians lived under clouds of dust and manoeuvred around mountainous rubble.

The result, eventually, was 45,000 new buildings, pleasantly situated on wide, tree-lined arteries; their design strictly dictated by height, setback and architectural design, now referred to as the Haussmann style. Fresh air, water and light reached into previously dingy neighbourhoods. Haussmann punned that he might consider the title ‘aqueduc‘ because he had multiplied the sewer infrastructure fivefold, creating a buried system of underground channels and aqueducts that remain a tourist attraction to this day.

Palais Garnier © Wikimedia Commons

Light in the City

On Haussmann’s grand avenues, a flâneur was never out of touch with the splendid monuments that defined Paris, and by extension, French culture. The Arc de Triomphe sat like a spider spinning Haussmann’s web of streets into the world’s most beautiful traffic circle. The Opéra de Paris, commissioned from architect Charles Garnier and today known as the Palais Garnier, was a jewel at the terminus of the Avenue de l’Opéra. The Théâtre du Châtelet and the Théâtre de la Ville still sit like opposing twins on the Right Bank. The enlarged Hôtel Dieu replaced several medieval streets on the Île de la Cité. Novelist George Sand and poet and flâneur Baudelaire enjoyed strolling down the bright, broad new avenues, although Victor Hugo, ever the Romantic, insisted Haussmann’s improvements bordered on vandalism.

The Gare de l’Est, and Gare de Lyon were necessities, as were architect Victor Baltard’s iron and glass pavilions protecting Les Halles market. Bridges joined the left bank with the right, while parks at the city’s four corners provided citizens with much-needed green space.

Haussmann’s tomb in Père Lachaise ©Pierre-Yves Beaudouin-Wikimedia Commons

Georges Haussmann earned nicknames such as ‘Vice Emperor’ and ‘Haussmann the First’. As a convenient scapegoat for everything that was wrong with the Empire, Napoleon III sacked him. Haussmann’s documents and maps were incinerated during the Paris Commune of 1871, the same insurrection that would ironically spell the end of the road for Louis-Napoléon. Haussmann died in 1891 and was buried in Père Lachaise. His teenage footsteps through the city’s squalid streets were the foundation for his new Paris, which remains one of the modern wonders of the world.

From France Today Magazine

Lead photo credit : Baron Haussmann © Henri Lehmann / Wiki at the Musee Carnavalet

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in architecture, French history, Haussmann, Paris

By Hazel Smith

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *