In the Footsteps of Toulouse-Lautrec

Hazel Smith traces the legendary artist from a childhood marred by illness to the seedy underbelly of Montmartre, where his artistic talents flourished.

His stature may have been small but his talent was vast. So just how did the painter Henri de Toulouse Lautrec end up being a hard-drinking denizen of Montmartre, dying before his 37th birthday? To understand him, we need to explore the events and places which shaped his life.

Albi is a fortified town in Occitanie, where the abundant sunshine warms a palette of terracotta brick. It was a stormy night on November 24, 1864, when Henri was born at the home of his great aunts, the first son of Count Alphonse and the Countess Adèle de Toulouse-Lautrec, cousins from an aristocratic family, whose abundant wealth trickled down from a genealogical line of knights and governors, dating back to the Crusades.

Henri spent his early years at the 12th-century Château du Bosc, amidst farmlands near Camjac, where Aubusson tapestries warmed the stone walls and dogs drowsed by the impressive fireplace, while young Henri mused over the works of Jules Verne and planned childhood mischief.

Chateau du Bosc

A DIFFICULT CHILDHOOD

Idyllic as it sounds, Albi would never be Henri’s permanent home. He spent his childhood travelling from château to spa to Parisian apartment at the whim of his much-beleaguered mother. Count Alphonse was a wealthy eccentric, with a fondness for appearing in public in costume or barely dressed at all. He once disappeared from a restaurant only to send his wife a missive a fortnight later that read, “Send ferrets”.

Summers were spent at the Château de Celeyran, his mother’s family retreat in Salles-d’Aude. Set among vineyards, this beautiful Italianate villa was where the fragile Henri enjoyed the company of his aunts, uncles and cousins. He was passionate about drawing and honed his skills on nature rambles with his uncles. In 1872, he and his mother moved to Paris where eight-year-old Henri took art lessons from René Princeteau, a family friend who had a studio at 233 rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré.

It was during his first year of formal schooling at the Lycée Condorcet that his mother realised Henri was more that just a frail child: other students had taken to calling him “Little Man”. After a round of health spas, she placed Henri under the care of Dr Verrier in Neuilly. Then the adolescent Henri broke his thigh bone after slipping on a waxed floor. After the subsequent break of his other leg, his bone growth stopped and Henri’s height never reached five feet. His stunted growth and propensity for broken bones was a result of the inbreeding within his family. His parents were first cousins and before them, generations had ensured the gene pool remained undiluted. Often referred to as Toulouse-Lautrec Syndrome, Henri’s condition was pyknodysostosis, a genetic disorder which causes short limbs, brittle bones, and abnormalities of the face and hands.

Henri Toulouse Laturec, at the Moulin Rouge, 1892-95, public domain.

ART AS A REFUGE

Henri’s strength was in his art. Often confined to bed, by 16, he had created around 2,400 drawings. He yearned to abandon school to further pursue his artistic interests. Princeteau landed him an interview at Léon Bonnat’s studio in Paris. Writing to an uncle in March of 1882, Henri happily informed him, “By unanimous opinion, I‘m going to visit Bonnat… Princeteau is going to introduce me”. By the age of 18, he was living permanently at his parents’ Paris pied-à-terre in the Hôtel Perey, in the rue Boissy d’Anglas.

Known as the favourite art teacher of millionaires, Bonnat took an instant dislike to Henri, and his time there was short-lived. In 1883, he enrolled at Fernand Cormon’s atelier in Montmartre’s rue Constance, working alongside other young artists such as Van Gogh, whom he would one day paint. Cormon encouraged his students to explore their surroundings for inspiration, and Henri looked to the colourful cabaret and brothel life of Montmartre. With his distorted figure, bowler hat and cane he became a familiar sight in the Montmartre underworld, peopled by prostitutes, pimps, comediennes and clowns, and it was here that Henri started on the path to alcoholism.

As 19-year-old Henri was embarking on his bohemian life, his parents separated and his mother bought the Château Malromé in Saint-André-du-Bois. Already disowned by his father, the struggling artist’s budget was sorely reduced and, unable to pay his rent, he camped out at 19 bis rue Pierre de Fontaine, the home of fellow student René Grenier and his wife Lily, who modelled for Degas. Henri often relocated within Montmartre and kept his living quarters separate from his studios.

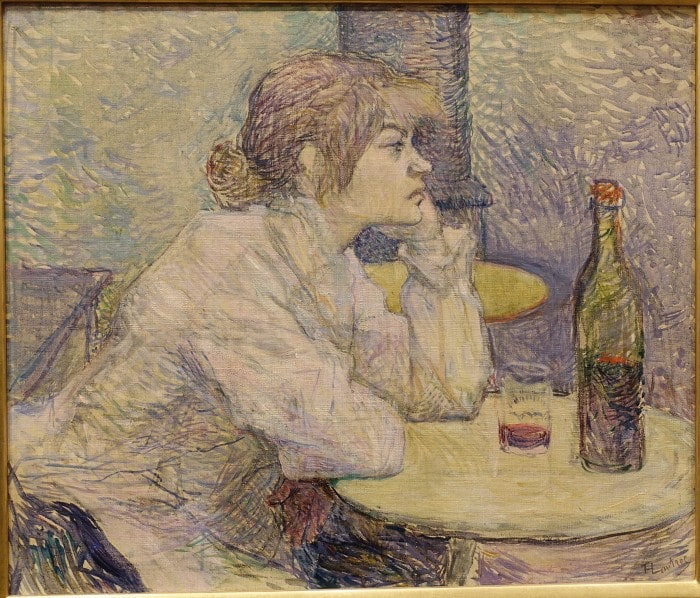

In the spring of 1887, he rented a top floor studio in a large house at the intersection of Rue Caulaincourt and Rue Tourlaque. There were artists on every floor and Henri’s studio became the focal point, where an endless stream of friends and fellow artists congregated to enjoy lively discussions and the potent pick-me-ups he mixed. At last, Comte Henri Marie Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa was making a name for himself in the art world, with works such as The Laundress, The Hangover and Rice Powder, featuring his close friend Suzanne Valadon.

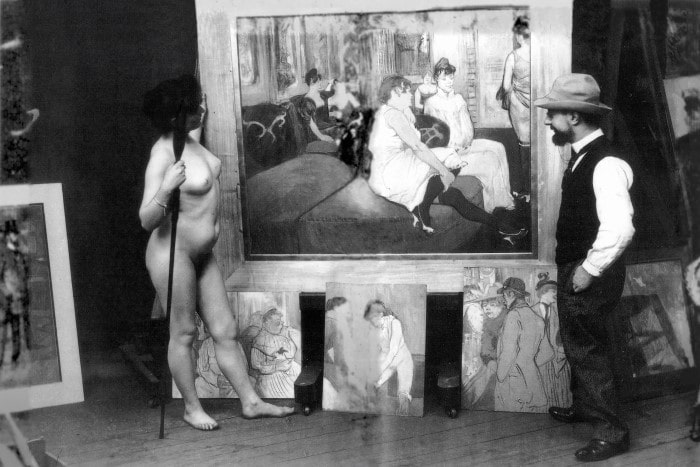

Toulouse-Lautrec in his workshop with nude model, photo by Maurice Guibert, 1895. Public domain

POSTER BOY

The décor of Toulouse-Lautrec’s studio showed him to be a collector of unusual and novel objects. Apart from a ladder, an easel and a spectrum of colourful paintings stacked against the wall, it included rush-seated chairs and a divan amply piled with cushions. His bric-a-brac included dusty toys, dumbbells, Japanese vases, dancing shoes and an array of hats, including a Samurai helmet. Photos from this time reveal his propensity for dressing up. Artists and circus people were often kindred spirits; bohemians on the fringes of society due to their unconventional occupations and relaxed morals, and Toulouse-Lautrec became a regular at the Cirque Fernando, where he would sketch the artists, creating some of the most iconic posters of the era.

His foray into graphic art marked a complete departure from the bourgeois world that the Impressionists depicted. In 1889, the Moulin Rouge opened its doors, and Toulouse-Lautrec became an habitué. Commissioned in 1891 to create posters for the cabaret, his large, colour-rich advertisements made the venue famous. During absinthe-soaked evenings, he sketched the red-scarfed cabaret artist Aristide Bruant at the Ambassadeurs, and Jane Avril at the Divan Japonais, and his reputation was secured, his unique aesthetic defining the Belle Époque. So popular was his work that his devotees peeled off new posters before the glue had even dried. Disliking living alone, Toulouse-Lautrec convinced a madam to rent him a room at La Fleur Blanche, a lavish brothel in the rue des Moulins, which he gave as his address for his business appointments. There he captured many of the prostitutes in candid, sometimes tender poses. The women nicknamed him “Coffee-pot” due to his odd physique.

The Hangover (Suzanne Valadon), by Toulouse-Lautrec, 1887-1889, © Wikimedia commons. Located at Fogg Art Museum, Harvard

Toulouse-Lautrec often spent weekends at the country home of the Natansons, the power couple behind the art magazine La Revue Blanche. At La Grangette in Valvins, he tempted these fair-weather friends with gastronomical delights. Along with fellow artists, Bonnard and Vuillard, days there passed by in a blur of music, plays, picnics and games. In 1897, his alcoholism worsened. After a successful exhibition at the Goupil Gallery in London, his work ethic began to slide and his art often went unfinished. Paranoid delusions haunted him, he was sometimes badly beaten on his nocturnal wanderings, and he became grey, haggard and sick. To his friends, it was obvious he needed desperately to dry out.

In March of 1899 they arranged to take him to a clinic, the Folie-Saint-James in Neuilly, where he spent three months. From there, he went to stay at his mother’s Malromé refuge, but began drinking anew upon his return to Montmartre. His condition worsened and he became confined to a wheelchair. At his mother’s estate, he experienced a series of strokes, the last of which killed him on September 9, 1891. He was 36. He was buried in Verdelais, Gironde. The thousands of works he left behind reflect his strange and vibrant life: his subjects were real people whose resilience echoed his own.

DETAILS

The Musée Toulouse-Lautrec in the Berbie Palace, Albi, houses the world’s largest public collection devoted to Henri de ToulouseLautrec.

At the Château du Bosc guided tours are available year-round.

Château Malromé has been recently renovated and is now a vineyard and wellness centre.

Photo ops only at his birthplace at 12 rue de la Toulouse-Lautrec, Albi.

His Montmartre studio straddles the corner of rue Caulaincourt and rue Tourlaque.

From France Today magazine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in art, culture, Toulouse-Lautrec

By Hazel Smith

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY