Exploring Saint-Paul-de-Vence, Where James Baldwin Took Refuge in Provence

With Jules B. Farber’s book about US writer James Baldwin’s exile in Saint-Paul-de-Vence recently published, Justin Postlethwaite reflects on the Provence village’s enduring appeal for artists

On a sultry summer’s morning, 10am on a Saturday to be precise, the day begins slowly at the iconic Café de la Place. Here in the historic, artist magnet village of Saint-Paul-de-Vence, high in the hills behind Nice, it’s breakfast time – albeit a late one for the locals or tourists emerging from a well-earned grasse matinée.

The sights and sounds are almost clichéd in their Provençal-ness: mixed in with the satisfying crunch of croissants, you hear cicadas chirrup in the bushes while the click-click of clattering boules wafts from the make-do pétanque court next door. Here, a smiling clutch of ‘gentlemen of a certain age’ take turns to lob their silver weapons of choice, offering one another gentle ridicule and encouragement in equal measure.

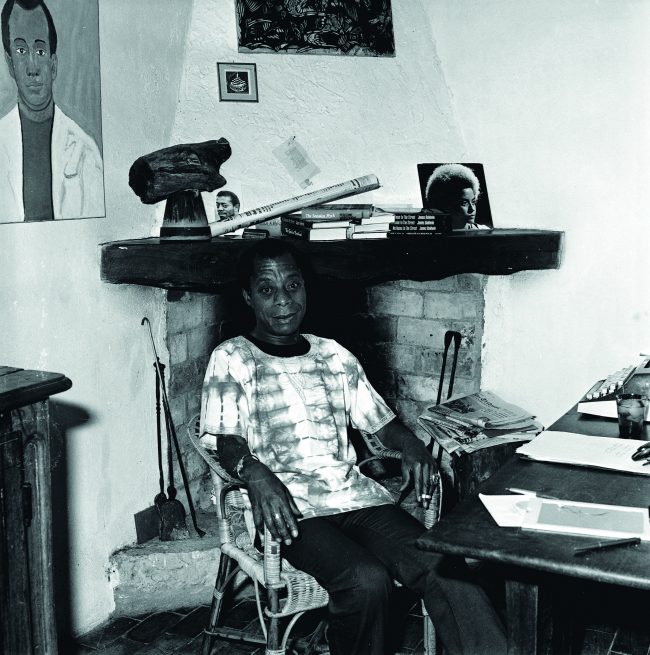

James Baldwin in his office. Photo courtesy of Pelican Publishing Company

Very little has changed at this ancient fortified settlement – aesthetically, at least – for many decades, so only the slightest leap of the imagination casts you back to a time when the village served as a cultural melting pot for some of France’s best-known film faces and creative minds.

On pretty much any Saturday from the ’60s to mid-’80s, you would have seen famous faces mingling with locals over a drink or games of pétanque. Actor and singer Yves Montand often played with acting pal Georges Géret; you would also see singer Henri Salvador and Italian-born actor Lino Ventura – all of them happily lobbing boules in the exact same spot.

“Kiss the Fanny” in the cafe. Photo: Justin Postlethwaite

Perhaps one of them would have been on speaking terms with the Kiss Fanny sculpture of a lady’s behind, now on display inside the characterful café. Tradition dictated that anyone who capitulated by a horror-show score of 13-0 had to kiss the cheeky fesses created by artist César.

Games of boules in the village. Photo: Justin Postlethwaite

Montand met his future wife Simone Signoret in 1949 at what was then a humble inn, the Colombe d’Or (more of which later), right opposite the café. Its owner, Paul Roux, would go on to serve as a witness at their wedding at the town hall in 1951, alongside poet and screenwriter Jacques Prévert. Today as you wander the village ramparts you can spot Prévert’s former home – he was initially lured to the region to work at Nice’s Victorine film studios during the war.

Poet Jacques Prévert’s house. Photo: Justin Postlethwaite

A street in Saint Paul-de-Vence. Photo: Justin Postlethwaite

HAVEN FOR CELEBRITIES

Saint-Paul-de-Vence became a destination of choice for French ‘culturati’ soon after Cannes hosted its inaugural film festival in 1946; it was a tranquil haven for celebrity overspill.

Following the lead of previous brush-wielding frequenters such as Picasso, Matisse, Braque and Miró – who had traded artworks, some still on display, in return for board and lodging at the Colombe d’Or – the place became a veritable haven for writers, painters and thinkers seeking sun, creative inspiration and a quiet rural life. Marc Chagall lived and worked here (he is buried in the village’s cemetery, which sits at the ‘prow’ of the village, if you imagine it as a boat shape), as well as former Rolling Stones bass player Bill Wyman, who was friends with him, and himself had a photography exhibition in the village a few years ago.

Chagall’s grave. Photo: Justin Postlethwaite

All left their mark on the village and are remembered fondly. But the one artistic arrival who came to call the village home, and yet does not get the recognition he merits, is the American writer James Baldwin (‘Jimmy’ to his friends), who came here in 1970 and who, in time, would count Wyman, Chagall and Montand among his friends.

The social and political activist, civil rights spokesman and writer has been the subject of long overdue attention and reappraisal recently, not only in the critically-acclaimed documentary film I Am Not Your Negro, but also in Jules B. Farber’s superb book on Baldwin’s time in Saint-Paul. Additionally, it has just been announced that Oscar-winning Moonlight director Barry Jenkins has chosen Baldwin’s 1974 novel If Beale Street Could Talk to be his next film project.

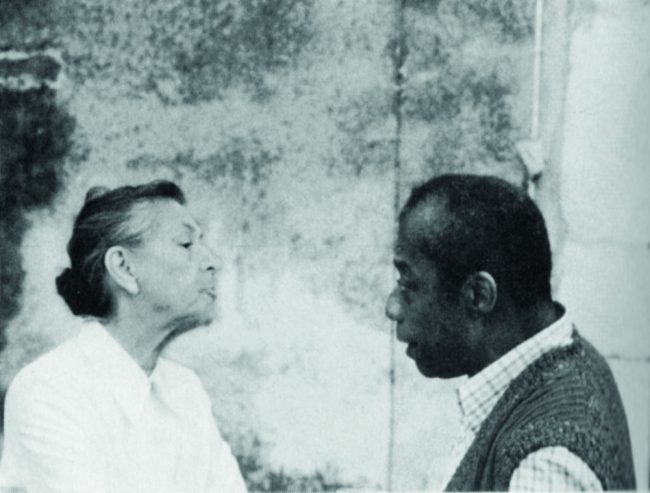

Baldwin and President Mitterand. Photo courtesy of Pelican Publishing Company

Farber’s book is meticulously researched and features countless interviews with those who knew the writer and his friends/drinking buddies during the years he spent in Saint-Paul until his death in 1987, aged 63. It presents a picture of a man who became deeply fond of the village, was a lively socialite with an open-door policy, and who welcomed many of his American friends such as Ray Charles, Harry Belafonte, Nina Simone, Ella Fitzgerald, Sidney Poitier and Miles Davis to stay whenever they were visiting or performing at one of the notable jazz festivals on the Riviera. All of this despite initial hostility towards him, not least from his openly racist landlady, Jeanne Faure (though she went on to become his greatest ally).

Harry Belafonte dining with Jimmy. Photo courtesy of Pelican Publishing Company

As a gay black man, it cannot have been easy for Baldwin to fit in here. ‘‘Initially, there was suspicion and fear about suddenly having a black man actually living in their midst,’’ says Farber. ‘‘Locals – primarily farmers and wine growers who had never witnessed such a phenomenon – were aggressive in their contact. For them, he was clearly a strange creature from another world. They were insulting and treated him with disrespect. It was racism as he had experienced in the US.’’ (The very reason he traded Harlem for the Riviera in the first place; that and close FBI scrutiny.)

A walk along the village ramparts. Photo: Justin Postlethwaite

However, Baldwin’s charisma and openness stood him in good stead. ‘‘Jimmy confronted the tormentors with his great smile and open-heartedness that broke down the barriers, leading not only to his acceptance but to his being loved in the village.’’ His landlady soon became very fond of him, often letting him delay his rent payments. ‘‘Jimmy’s move to Saint-Paul meant he could live in peaceful splendour in a great house, surrounded by local creative friends, visited frequently by renowned American musical and literary friends – but with none of the hassle and confrontations he had been experiencing in the US.’’ Baldwin continued to write though, as Farber points out, these last 17 years of his career were not his most productive.

Baldwin with his landlady, Madame Faure. Photo courtesy of Pelican Publishing Company

The Colombe d’Or was a favourite haunt. It was (and still is) run by the Roux family, which had adopted him as one of their own. ‘‘He made a point of being there to share in the ritual of the youngest daughters being put to bed,’’ says Farber. He also frequented the Café de la Place and enjoyed watching pétanque. ‘‘Jimmy went to many of the exhibitions in the Fondation Maeght sculpture gardens just outside Saint-Paul.’’

The entrance to the Colombe d’Or. Photo: Justin Postlethwaite

SAINT-PAUL TODAY AND ‘LA MAISON DE JIMMY’

As for the village today, its quaint visual allure remains unchanged – tiny, tantalising streets branch off the main rue Grande (it’s narrow, of course) and are lined with cute boutiques, restaurants and galleries harking back to a gentler epoch. But if the village has one foot in the past and antiquity serves as inspiration, there is plenty of innovation going on here too. Among the next generation of go-getters is young parfumier and all-round creative whirlwind Sonia Godet, who has resurrected her family’s traditional perfume business, Maison Godet. Hers is an apposite new retail outlet for the village that once supplied perfume capital Grasse with blooms.

Sonia Godet, parfumier. Photo: Justin Postlethwaite

Next door you can shop for gorgeous fans (éventails) handcrafted by Patricia Rémus at Révolv’Air – designs range from the funky to trad-Provençal. Even the business of selling vintage wines has a fresh, unstuffy new face in Saint-Paul – descend into the wine cellar of La Petite Cave de Saint-Paul and two smiling sommeliers, Frédéric Theys and Romain Calzia, will happily advise on all manner of tipples, from local rosés to Bordeaux’s carte-bleue busters. They also sell craft beer from Nice, in case you did not know such a thing existed – a delicious whistle-whetter after a hot day’s exploration.

Hand-crafted fans at Revolv’Air. Photo: Justin Postlethwaite

The catering in the village is pretty special too, again with fresh faces leading the way. Highly recommended is Le Caruso, a family-run, vaulted little hideaway combining flair with value near the Chapelle des Pénitents Blancs (do pop into this church to see its striking Jean-Michel Folon mural).

Romain at La Petite Cave. Photo: Justin Postlethwaite

With all these sociable, creative youngsters around, as well as the umpteen artists in residence, James Baldwin would surely have loved the village today, and would have found plenty of new friends to share a drink with. The Colombe d’Or still retains its secluded charm, even if it has a more exclusive air these days.

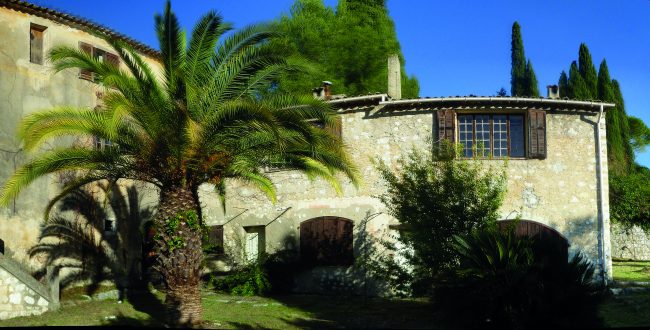

James Baldwin’s house. Photo courtesy of Pelican Publishing Company

The sad thing, however, is that the ongoing tale of a permanent physical legacy for Baldwin’s place in the village’s history looks set for an unhappy ending. The spacious mas on chemin du Pilon in which he lived and worked until his death (he never owned it, though it is claimed that landlady Faure wanted to leave it to him before she died), is under imminent threat of demolition by property developers – indeed, some of it has already been knocked down.

An association called Les Amis de la Maison Baldwin, led by Hélène Roux and American novelist Shannon Cain, has been trying to raise funds to save the building and convert it into a residence for artists and writers.

‘‘Our aim in the short term is to impede the construction of 19 luxury flats on the site,’’ explains Shannon. “Long-term, we are certain that US philanthropists will step forward in order for us to purchase the house.’’

Farber agrees: ‘‘I think the Baldwin house should be saved, if that is at all still possible at this late stage. It would be a fitting tribute to the great American writer who made his home in Saint-Paul.’’

Should the bid to save the property fail, the least visitors can do is raise a glass to the writer at the Colombe d’Or or the Café de la Place.

Contacts: Saint-Paul-de-Vence Tourist Office is located at the foot of the village, past Café de la Place on your right. Les Amis de la Maison Baldwin can be found at lamaison-baldwin.org

James Baldwin by Jules B. Farber, with foreword by Jack Lang, is published by Pelican. Publish the book on Amazon below.

From France Today magazine

Rue Grande. Photo: Justin Postlethwaite

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY