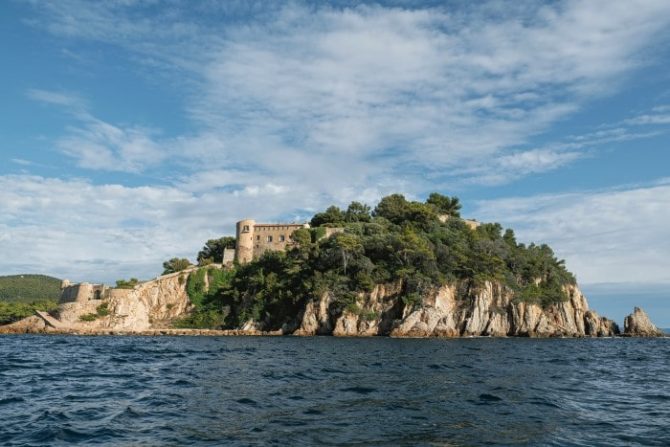

The Fort of Brégançon: A Presidential Retreat

Sitting off the Mediterranean coast at Bormes-les-Mimosas in the Var, the iconic Fort of Brégançon is where French Presidents come to relax, entertain dignitaries or simply work in peace. It features in a new book about Presidential Palaces, which invites readers behind the scenes of France’s hallowed halls of power.

Excerpted with permission from the publisher, Flammarion. Words by Adrien Goetz. Photography by Ambroise Tézenas

Why did the French government lumber itself with the Fort of Brégançon, a beguiling seaside residence where you can’t even go swimming? This democratic rock makes no claim to rival the princely rock of Monaco, yet it triggers all kinds of fantasies about an inaccessible, independent realm. The peninsula has its own microclimate: the ground is very dry, yet everything is humid, making a true botanical garden of this rocky clump in the sea. Rare species live in harmony, with olive and laurel trees, umbrella pines, Aleppo pines, and recently introduced lemon trees (in pots).

The fort is not a legacy of the French monarchy, although it boasts its own worthy heritage: Charles IX passed through in 1564 with his mother, Queen Catherine de’ Medici; Napoleon Bonaparte made a coastal inspection tour here after his first brilliant military victory, the siege of Toulon; and later, during the Empire, Napoleon turned it into a small garrison of veterans. Right from the ninth century there existed a medieval military post at Brégançon on the mainland (where a vineyard exists today, as can be seen when taking Avenue Guy Tézenas along the coast), but it wasn’t until the 15th century that defensive works were built on the islet, part of the Marquisat des Îles D’Or, a gift bestowed by King Francis I on the Baron de Saint-Blancard, his Master of Ships. In the late 16th century, the king sold the Fort of Brégançon to Boniface de la Môle (a name appropriated by Stendhal for his novel The Red and the Black). It later came into the Honoré de Gasqui family, who modernised the towers.

The French windows, installed during the Mitterand presidency ©Ambroise Tézenas

A MODERNISING TOUCH

During the First World War, Brégançon housed a small garrison but the French army abandoned the site in 1919 and it was rented out as a private residence. Robert Bellanger, a left-of-centre politician from Ille-et-Vilaine in the north, who had served as undersecretary of the navy under Prime Minister Camille Chautemps in 1930, rented what may have looked to him like a mini-version of Saint-Malo, minus the rain. He and his family happily lived there until 1963, when he was suddenly informed that his lease would not be renewed. A wealthy man (as co-founder of Bellanger Automobiles, a maker of splendid, gas-guzzling cars until it was taken over by Peugeot), Bellanger loved to host his friends in the fort that he had restored with all mod cons. He notably had running water put in. The lack of a spring had long been a problem for the island: without a water supply it was impossible to withstand a siege, as evidenced by the quick capitulation in 1524 when the Duke of Bourbon attacked it on behalf of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V.

Bellanger also had electricity installed, so that modern life could begin, and built the causeway, the road and the picturesque outer wall that evokes, at sunset, the Saharan location of Pierre Benoit’s fantasy novel Atlantida. It was thus Bellanger who turned an uncomfortable fortress into a gem perched amidst a picture-perfect Mediterranean setting. Perhaps General de Gaulle appreciated Bellanger’s 1930s taste; or maybe he enjoyed the account of the capture of the fort by Captain de Leusse at the end of World War II. Whatever the case, at no point did the general explain his reasons for making Brégançon a presidential residence.

He spent just one night there, before celebrating the 20th anniversary, on August 15, 1964, of the Allied landing in Provence. That was the basis of his decision to turn Brégançon into a residence for French heads of state. Perhaps he wanted to assert France’s attachment to this Mediterranean outpost. Yet having made the decision, de Gaulle himself never returned.

The blue furniture in the living room was originally designed by Pierre Paulin for the Élysée office of President Mitterand. © Ambroise Tézenas

POMPIDOU AND CIRCUMSTANCE

Renovation of the fort was completed by 1968. A job that might have called for the sober genius of Pierre Barbe – who reinvented a modern Provençal style for Anne Schlumberger’s estate at Les Treilles – went to a skilful naval architect, Pierre-Jean Guth, who enlarged, streamlined and modernised the site, building a guest wing while retaining its mildly monastic air. He did not go so far as to surf the Captain Blood/Iron Mask wave, which was all the rage in castles following the 1960s movies in which Jean Marais dashed and leaped through white-washed archways as the bad guys crumpled to the tiled floor.

Listed as a national monument in 1968, Brégançon was furnished by the National Furniture Depository, the better to host President Georges Pompidou and his wife for five years. The fort thus unobtrusively began to play a new role. The guard still fires a small canon and raises the colours every morning, but where de Gaulle envisaged another garrison – another rock of the French Republic – the new presidential couple saw a perfect vacation home where the family could spend time with friends, playing pétanque in sandals, going to Mass at the church of Saint-Trophyme in Bormes-les-Mimosas, and having relaxed lunches with the likes of Pierre Soulages and Françoise Sagan.

Just opposite was the island of Porquerolles, which in 1891–92, along with the Îles d’Or, inspired Henri-Edmond Cross to paint one of his finest works. This vibrant canvas, which now hangs in the Musée d’Orsay, was a harbinger of abstraction and once belonged to critic Félix Fénéon before it was acquired by the nation in 1947. Although the fort has no boat and no real beach (regular attempts since 1972 to build a sea wall have been constantly undermined by currents), it has a magical view and pleasant sea breezes.

The beach, highly prized by French paparazzi. © Ambroise Tézenas

HOW TASTES CHANGE

In 1974 when Giscard d’Estaing became president, he sent almost all of Brégançon’s Pierre Paulin furniture back to Paris, turning the fort into a Provençal family home where solid armchairs and commodes, again supplied by the National Furniture Depository, set the tone. A tiny beach reached by a very steep stairway along the rock face enabled France’s first sporty president to go swimming. Super-8 movies were made of the children, later proving that Jacques Chirac hadn’t been as poorly received there as he had claimed.

The fort has only two neighbours. Sarrazin Tower houses the family of the grand dukes of Luxembourg, and enjoys extraterritorial status that extends as far as the road, making the property the grand duchy’s only coastline. The villa La Reine Jeanne was the home of the legendary Commandant Paul-Louis Weiller, a war hero, arts patron, member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, and collector of fine houses and good friends. In 1994 his granddaughter Sibilla married Prince William of Luxembourg. The French president never fails to entertain these princely neighbours.

Faithful to Pompidou’s memory, President Chirac also stayed at Brégançon, which his wife rather liked. The Chiracs reinforced the classic French taste that some interior decorators laughingly call “Provençal Gustavian”. President Nicolas Sarkozy, however, preferred nearby Cap Nègre, the mansion belonging to the family of his wife, Carla Bruni. Then President François Hollande shunned the fort entirely, temporarily authorising the Centre for Historic Monuments to open it to the public – an option that had already worked at Rambouillet, the presidential summer residence 50km from Paris.

The upstairs hallway with its red earthenware. © Ambroise Tézenas

Comparing the current state of the Fort of Brégançon to old photographs, it seems like a whole new window has been opened. An above-ground pool among the greenery finally makes swimming possible – which doesn’t exclude under-sea diving with mask and snorkel (after having swum across Luxembourg’s territorial waters). The flowery curtains are gone, as are the floral and olive-branched carpets. Paulin’s Élysée lamp seems at home beneath the pure vaulted ceilings, while his red, white and blue Amphis sofa – designed for the French pavilion at the Osaka International Exposition in 1970 – is a kind of allusion to Pompidou; it seems as though it has been there forever, when in fact it arrived when the fort was managed by the Centre for National Monuments.

The bedsteads are gone, but Paulin’s large, module shelving stretches along one wall, while the curves of his big table and chairs harmonise with the interior volumes. In the president’s office – connected to the bedroom via a rather theatrical staircase with halflanding – a tapestry by Geneviève Asse seems to echo the large canvas that similarly imparts a horizon to the cabinet meeting room in the Élysée.

The office and bedroom overlook the sea in a sparse setting that matches the spirit of the place. The bedrooms of the aide-de-camp, physician, and chief of staff remain spartan with their iron beds and shower stalls. The former chapel, which has long served as the TV room, now hosts the blue furniture Mitterrand used in his Élysée office. There thus reigns over the fort a subtle presidential idiom made up of historic references. The most striking thing is the variety of viewpoints. A table placed on the belvedere can be used for work or meals, while another table, next to the cannon beneath the French flag, offers a different view along the coastline. Brégançon, now completely connected to the modern world, thus enables the head of state to work differently, from different angles.

As seen in France Today Magazine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in fort, France history, history, mediterranean

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY

REPLY