How Traditional, Regional Viennoiseries are On the Rise in France

Emily Monaco examines the changing face of viennoiserie offerings in the French capital, as quality, choice and a resurgence of regional specialities buck the boulangerie status quo.

If you’d walked into a Parisian bakery 20 years ago, the viennoiserie case would have featured a small cast of familiar favourites: croissants, pains au chocolat, pains aux raisins. Perhaps a chausson aux pommes or a chocolate-studded pain suisse. But these days, some newcomers are joining these stalwarts: American doughnuts, Polish babka, Scandinavian cinnamon buns… and some that aren’t actually that foreign at all, hailing from la province.

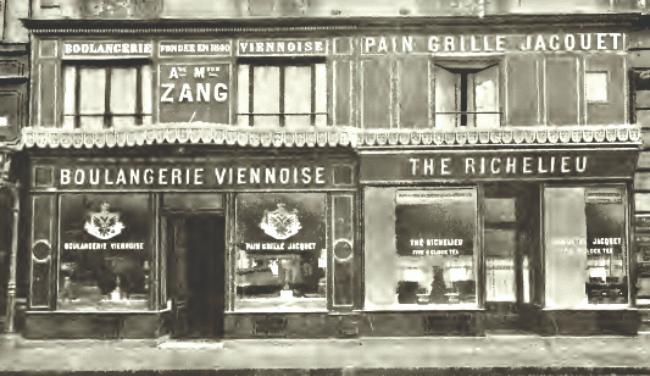

Boulangerie Viennoise, circa 1909 © Wiki Commons

Novelty in the viennoiserie case is, of course, in keeping with tradition: even the croissant is only barely Parisian. It was thanks to the 1837 opening of August Zang’s Boulangerie Viennoise that Parisians got their first taste of yeast-leavened Austrian specialities like the kipferl, whose crescent shape inspired the flaky, laminated marvel that would become known as the croissant.

But what makes the croissant and its fellow breakfast buns ‘viennoiseries’ isn’t necessarily their purportedly Viennese origins, but rather their inscription, not in the tradition of pâtisserie but that of boulangerie. And of course, France is home to a panoply of regional variations. Perhaps the best-known regional example is the Breton kouign-amann, which conquered the capital in the early 2000s, according to culinary instructor and bestselling cookbook author Susan Herrmann Loomis, who notes that while some regional offerings like tarte Tatin and madeleines predated her own Parisian arrival in the early 1980s, “kouign-amann is newer, as of the past ten to 12 years”. It is perhaps thanks to Georges Larnicol, who began selling miniature ‘kouignettes’ in Paris in 2010, that the rich confection of dough laminated with butter and sugar began to conquer Parisian bakery cases. These days, the kouign-amann is omnipresent in Paris: at Blé Sucré in the Marais or Maison d’Isabelle in Saint-Germain, revisited with a toasted kasha topping at Sain Boulangerie or crusted in black and white sesame seeds at Le Petit Grain.

Read More: Une Journée Avec…a Kouign-Amann Baker

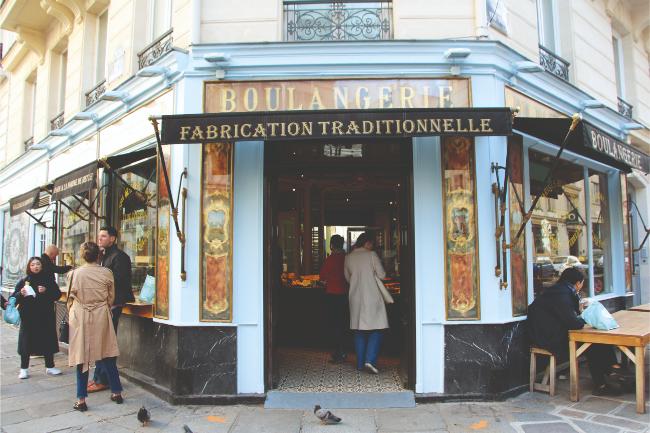

© Emily Monaco

But kouign-amann is far from the only regional viennoiserie to make it big in the big city. You’ll find Bordelais canelés at Boulangerie Julien while the Ardennes’ tarte au sucre is a star of the case at Tapisserie. Boulangerie Chevalier and Gosselin both make stunning oranais, that Algerian marriage of puff pastry, crème pâtissière and apricots. Sometimes, the regional sway is revealing, as at Chez Meunier, where the Norman head baker bakes local pain brié, and at Pralus, which was founded in Roanne and is known for its pink praline-studded brioche. At Stohrer, Paris’ oldest pastry shop, the eponymous founder’s experience baking for the exiled Stanislas I in eastern France is evoked in the offering of kougelhopf; at Aux Péchés Normands, Normandy’s bounty finds its way into the grillé aux pommes, a pastry rectangle protecting a layer of apple compote with a ‘grille’ of puff pastry.

Such creations have also firmly entered the mainstream. At La Flûte Gana, the Dauphinois Bugnes, with its hint of fleur d’oranger, is sold alongside more typical croissants and pains au chocolat. At Brigat’, which is run by a pair of Italian brothers, you’ll find not just Catalan cream-filled brioche but Norman bostock in ever-changing permutations from maple-pecan to raspberry-peanut. Even industrial giant Paul peddles its own grillé aux pommes, praline-studded brioche and tarte au sucre.

For culinary journalist Domenico Biscardi, this new wave of old classics has its root in a wider French desire to rediscover regional terroir following years of the provinces being maligned in the French cultural consciousness. “People from the regions came up to Paris, to work, to study,” he says. “But today, we’re seeing the opposite.”

Maison Pralus

Escape to the country

In the wake of Covid, many Parisians are choosing rural areas not just for a better quality of life but to reconnect with their roots. “There’s a core movement in France of promoting regions again,” he says, “including in pastry, bakery and viennoiserie, of course.” Indeed, perhaps more so than bread or pastry, viennoiserie is an excellent inroad for such change. “For most, viennoiserie is a sweet, inexpensive, simple product you can have at any moment of the day, and above all, first thing in the morning,” he says. “It’s the dream entry point for products that aren’t that well-known yet. And above all for French regional heritage.” For some bakers, like Carl Marletti, reaching into France’s regions for inspiration is a way of adding a dose of nostalgia. His affection for the Basque Country inspired his line of gâteaux basques, a shortbread pie he fills not just with traditional cherry but with zippy citrus curd.

For others, venturing into regional specialities is a way of grounding an otherwise international repertoire: when English chef Ed Delling-Williams first opened Le Petit Grain in 2018, the kouign-amann was the only French offering among lamingtons and fluffernutter tartlets. “At the beginning, we didn’t even do croissants or pains au chocolat,” he recalls, noting that the very philosophy of the shop was to depart from the trodden path. Rather than opt for an on-trend cronut, he decided to look west, to the kouign-amann, which, he says, “is actually just as delicious but more traditional”.

The trend also restores quality to a category that has been long doomed to industrialisation. Despite their simple allure, viennoiseries are time-intensive bakes: Christophe Vasseur, of Du Pain et Des Idées, notes that his croissants take a whopping 34 hours to make from start to finish. So it’s perhaps no surprise that an estimated 60 to 80 per cent sold in France are of the frozen, mass-produced variety.

Read More: Une Journée Avec…an American Pastry Chef in Versailles

Du Pain et des Idées © Emily Monaco

“There’s no legislation imposing, in an artisanal boutique, that viennoiserie be made entirely on-site,” he says. “For bread, yes, but for viennoiserie, you can buy everything frozen from a big industrial producer who makes something that does the job but from a flavour and nutritional standpoint is a catastrophe.”

It is what motivated him, 22 years ago, to found his bakery with a focus on excellent ingredients, time-tested recipes, and a tight selection of regional specialities: the mouna, a brioche spiked with orange blossom water from Algeria’s pied-noir community; Provins’ niflette, featuring a base of puff pastry crowned with pastry cream; and the sacristain, a twist of pastry cream-lined laminated dough hailing from the Vaucluse. He eschews the kouign-amann, dubbing it too rich, as well as the oranais, which would oblige him to work with out-of-season ingredients or canned fruit.

Vasseur is perhaps most famous, however, for a viennoiserie of his own creation: a revisited pain aux raisins, which he considered calling the tourbillon (whirlwind) before ultimately settling on escargot (snail). “Putting a bit of poetry in what we do is essential,” he says. And while his escargots feature a selection of fillings, the chocolate-pistachio iteration has become, for Delling-Williams, the house special, a viennoiserie with major star power.

Kouign-Amann © Shutterstock

New creations

Erwan Blanche, co-owner of Boulangerie Utopie, recalls other early signature viennoiseries, such as Café Pouchkine’s vanilla croissant and the Ispahan iteration at Pierre Hermé. “There were already a handful of big houses that stood out,” he says. “But it wasn’t the boom that we see today.”

These days, viennoiserie cases have become as changeable as boutique windows, with inspiration hailing not just from French regions but from far further afield, from Danish pastries at Le Petit Grain and Ten Belles to the reimagined croissant at Frappe whose shape evokes the Algerian corne de gazelle. Some bakers are even reappropriating American plays on French tradition, as with the cruffin at French Bastards, the pretzel-croissant hybrid at Boulangerie Michalak, or the New York Roll at Bo et Mie.

Blanche and his team, meanwhile, have gone so far as to invent a new viennoiserie every weekend for the nine years they’ve been in business. He relies, of course, on a few base forms, including the regional kouign-amann and tarte au sucre. But he has also created his own shapes, like a filled croissant flower or a chausson laminated with charcoal to create black-and-white striations.

This explosion of innovation is in part thanks to the arrival of new faces in the sector, many of whom are embarking on a second career in bakery arts. “There’s a common dynamic of creativity,” says Nicolas Roulleau, marketing director of Chez Meunier, who also cites a second, far more economic motivation.

“We’re obligated, to stand out from our competitors, to offer new things,” he says. “It’s like any car manufacturer brings out its new model that year, or Apple brings out its new iPhone. If we want to keep our clients, we have to offer novelty.”

But while pure innovation is certainly fun, France’s regions are far from tapped of inspiration. Marletti has recently created his own play on Nantes’ rum-scented, almond-based gâteau Nantais, while Delling-Williams, who now lives in Normandy, is tempted by the idea of an almond paste-stuffed tarte alsacienne.

At Chez Meunier, the team is constantly inspired by what Roulleau dubs ‘ancestral’ bakes, including the far breton. “We’re big fans of the old school,” he explains. “But we’re going to reimagine them, redesign them.”

Vasseur, meanwhile, is satisfied with his tried-and-true offering, noting that the lineup hasn’t changed in 22 years. “When you change too much, you can lose yourself,” he says. “I’m comfortable with the idea of keeping what I know how to do very well.” That said, he’s not opposed to new inspiration. “Maybe someday it’ll come, the day that I taste something in the countryside, in a little hidden bakery that’s still there and is still making a local speciality,” he says. “And I’ll say, but that’s amazing! What is that?”

From France Today Editors

© Emily Monaco

Lead photo credit : © Emily Monaco

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in bakery, baking, French food, French pastries, French regional specialties

By Emily Monaco

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *