Ernest Lavisse: A Little Book Makes a Big Comeback

It arrived in a bundle of second-hand books intended for a fund-raising sale – “it” being the Histoire de France: cours moyen by one Ernest Lavisse (18th edition, 1921). Worn round the edges, as might be expected in a book that first saw life in a school 95 years ago, it was an A5-size hardback of 270 pages.

To be honest, I wasn’t expecting much from it, but the language seemed simple enough to try reading it. The language is simple; even with my limited French, I only had to reach for the dictionary two or three times, when the meaning was not obvious from the context. And the book has a purpose in telling the history of France to children that won’t be found in any textbook today. I wanted to know more about Lavisse and his “cours moyen“.

“Histoire de France: cours moyen” by Ernest Lavisse

Ernest Lavisse was born in 1842 in a small French town close to the Belgian border; trained as a teacher, his career took him to the top, and he became personal tutor to the son of Napoleon III while still in his 20s. But everything changed for Lavisse with the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, and he returned to the academic life as a post-graduate student …. in Berlin. Back to France in 1876 he joined the staff of the Ecole Normale Superieure; in 1884 he took up a chair at the Sorbonne, was immortalised in the Academie Francaise, and returned to the Ecole Normale Superieure as director in 1904.

In 1892 Lavisse was commissioned to produce a scholarly history of France ~ 18 volumes published between 1903 and 1911, followed by a further 9-volume history of contemporary France, published between 1920 and his death in 1922.

No lightweight, then – so what was he doing writing a children’s history in a language so simple that I could follow the story with my tourist-level French? Part of the answer is right there on the front cover of the little book – “Enfant, tu vois sur la couverture de ce livre les fleurs et les fruits de la France. Dans ce livre, tu apprendras l’histoire de la France. Tu dois aimer la France, parce que la nature l’a faite belle, et parce que son histoire l’a faite grande.” Perhaps the simplicity is deceptive – histoire has two meanings, and does dois mean “have to” or “must”?

“Histoire de France: cours moyen” by Ernest Lavisse

This is history with a moral purpose: to instil into children the idea that they are picking up a torch that first flickered into life among the ancient Gauls and burned with varying degrees of brightness over the centuries, until it burst fully into flame with the Revolution, staying alight through all the shocks of two Empires and two disastrous setbacks in 1870 and 1914-18. The children taught through this book will have been in no doubt that they should carry the torch in their turn. A more cynical view is that Lavisse saw in Berlin just how much more disciplined German schooling was compared to the French system, and he was determined to bring that discipline into French schools in order to dispel the defeatism of post-Imperial France.

If Lavisse had wanted his message to spread through the schools of France, he more than succeeded. Born out of a series of talks for the children of his home town, the first edition of a Petit Lavisse came out in 1884, close on the heels of the Jules Ferry reforms of French education: by 1921 (the year when my copy reached its young readership), 1,270,000 had been published, and the book remained in print until the 1950s.

So what is it that catches the imagination in such an ordinary little book? Lavisse must have known the old adage about training – “tell them what you’re going to say; say it; tell them what you’ve said” – for each chapter begins with a couple of lines itemising its contents. The text then takes each item in turn and breaks it down into digestible paragraphs, often including a story to illustrate the theme, an engraving of the key event, and sometimes a moral (printed, for greater emphasis, in italics) to bring home the significance of what has just been read. Finally, a half-page resumé covers the ground once more. Revising for an exam would be child’s play: read the chapter once or twice (easily done; the sentences are short and punchy and there are no long or unfamiliar words), then learn the resumé off by heart. There are even a few pages dotted around with examples of the sort of exam questions that might turn up. Questions, though, which might tax the modern pupil – “What were the causes of the Seven Years War? Was France right to involve herself in it? What did she lose through that war ?” (The answer, in case you’re wondering, is Canada.)

“Histoire de France: cours moyen” by Ernest Lavisse

Lavisse himself says in the preface that he has tried to give the book the feel of a clear, familiar story, told in a way that appeals to the imagination and sticks in the memory. Taken at random, these examples, in my amateur translation, give you an idea of what Lavisse wants you to learn from the events of that story:

“(France in the 1st century) was not yet a nation, for a nation is a land where people should love one another.”

“That day (in 1302) when the three estates were met together, you could begin to see that there was a French nation.”

“It was because the kings didn’t want to make reforms at a time when they would have helped that there was a revolution (in 1789), that’s to say a complete change.”

“It was war that brought him (Napoleon) to the throne: but it was through war that he was destroyed.” “To his distress and to that of France, he had been an absolute master. He had shut down all political freedom. Nobody could prevent him making the mistakes that brought misery to France.”

(On Napoleon III’s 1851 coup d’état.) “Once again, France, frightened of the risks of freedom, gave itself a master.”

(And, almost finally, describing the 1914-18 trench warfare:) “Children of France, don’t ever forget; if your fathers and brothers put up with all that misery, it was for you, so that you won’t have to put up with it later on, so that never again will you be able to have a world war.”

In an endpiece to the book, Lavisse tells his young readers that he is approaching his 60th birthday and that for 50 of those years he lived in a France that was “beaten, broken up and humiliated”. He appeals to the schoolchildren of France to face up to the work of reconstruction that lies ahead of them. Years later, a columnist in Le Figaro mused “is it just nostalgia to look back with regret to a time when primary school children knew more about their history than today’s university students?” Speaking for myself, no it isn’t.

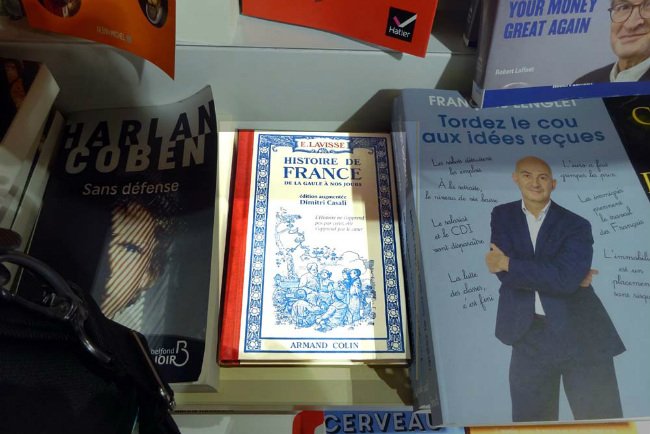

Lavisse at the Nice airport

Then – another chance encounter – passing through Nice airport last week, I spotted a Petit Lavisse in the current affairs section of the bookshop. A Lavisse with a difference, though, for this was an augmented edition where the historian Dimitri Casali had brought the story up to 2013, the centenary of the original text.

The cover of the new edition stakes its claim with Lavisse’s own words: “L’Histoire ne s’apprend pas par coeur, elle s’apprend par le coeur” and Casali’s format is faithful to the original, as is his simple language, but his update stops in a bit of a rush with the events of 1968. Perhaps contemporary history is a little too complicated?

Pick up your own copy on Amazon below:

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY