Nice and the Belle Époque

Imagine the scene: It is November 1900 and you are a cash-strapped but enthusiastic law student at a college in Paris. A wealthy, elderly relative has invited you to join a party he is taking to his recently built winter residence in Nice. The journey gets off to a thrilling start as you join the Méditerrannée Express at the fabulous new Gare de Lyon in Paris. In the dining car you meet Russians, Austrians and Swedes, as well as many British travellers who have boarded at Calais and are en route to winter on the Côte d’Azur.

The conversation, like the wine, flows easily and you are entranced by the elegance and bonhomie of your travelling companions. Later you discover that the famous Wagons-Lits sleeping car lives up to its reputation as the height of luxury on wheels yet, despite the comfort, your state of excited anticipation interferes with sleep. After a long overnight journey you arrive in Nice at the brand new station and are driven by private carriage along the Avenue Jean Médecin towards the Place Masséna. It is a remarkable sight to see the new electrified trams replacing the horse-drawn models. Occasionally, a motor car will pass by – everyone turns to look – ever since your visit earlier in the year to the Exposition Universelle de Paris you are enthralled by the countless new technologies promised by this new century.

As you drive along the Avenue Masséna (renamed Avenue de Verdun after World War 1) you are struck by how much Nice seems to have changed since you first visited as a child. Everywhere are bright new buildings, private homes, offices, banks, galleries of shops, many built in the neo-classical style. With their ornate cupolas, balconies and decorative plasterwork, painted in shades of white and cream, they create a dazzling contrast against the deep blue Mediterranean sky. It is surprisingly warm compared to the chill of the Parisian winter and your spirits are lifted – what a holiday this promises to be!

The period of European history from the late 1800s to 1914 is often known as the Belle Époque. Entering a period of peace and prosperity following the Franco-Prussian War, France found itself at a cultural and technological high point, where many social and economic factors combined to create an environment which was ripe for invention and experimentation.

This was a time of confidence for European aristocracy, when the crowned heads of once-famed but now obscure kingdoms put aside their ancient rivalries and found time for pleasure and indulgence. It was a period of political stability and cross-border alliances which encouraged trade and travel to other European countries.

The Belle Époque was the precious moment in history when Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art was first widely appreciated and celebrated, when Art Nouveau with its sensuous curves and colours appealed to the fin de siècle sensibility. And with more relaxed attitudes in society came an inevitable flourishing of creative literature, popular theatre and music. Iconic cabarets such as the Moulin Rouge in Paris appeared to feed the demand for risqué and decadent entertainments, and the boundaries were pushed even further by those seeking a more Bohemian lifestyle.

The wealth of the aristocracy was secure during this era. Revelling in a new-found confidence many chose to flaunt their riches and opulence in the high society hot-spots of Paris and Vienna, as well as in the fashionable resorts of Biarritz, Deauville, Cannes and Nice. They were the talk of the town. What was the Prince of Wales wearing and where was he spending his time? Where could one purchase the latest in haute couture? Who was popular on stage? What famous new dish would master chef Escoffier create for his famous patrons? And not least, where were all these celebrities staying for their vacations? The answer to many of these questions were found in Nice.

Nice was finally ceded to the French state in 1860, following many years of division between the country and pre-Italian states. With its political future more secure, Nice could look forward to a period of stability and growth.

The arrival of the railway in 1864 was a major contributor to Nice’s reputation as a stylish and accessible winter destination. Over the course of the next few decades, new train lines and services were founded to bring wealthy travellers from the major European cities to the South of France via Paris. They were terribly slow by today’s standards but what they lacked in speed they made up for with opulent dining cars and plush Wagons-Lits sleeping cars.

The start of the service from Calais to Nice in 1886 – which later became known as Le Train Bleu after the colour of the sleeping cars – enabled wealthy British visitors to gain relatively easy access to the renowned winter sunshine of Cannes and Nice, where they could enjoy themselves, free from the Victorian/Edwardian moral restraints of home.

And so they came. At first a glittering succession of royal-blooded visitors from Russia, Sweden, the former Eastern European kingdoms and Denmark, not forgetting King Leopold of Belgium and the British Prince of Wales’s “set”. These noble travellers were followed by the nouveaux riches and the wannabe fashionable: bankers and financiers, merchants and traders, industrialists, distinguished military men, successful men of business and a smattering of artists and writers in search of sunshine, patronage and inspiration.

If you had means, it was suddenly no longer so appealing to rent a house or a suite of rooms. Why not find a plot of land near the centre, or better still right on the coastline, commission an architect and build a mansion house that would reveal the full extent of your taste and affluence?

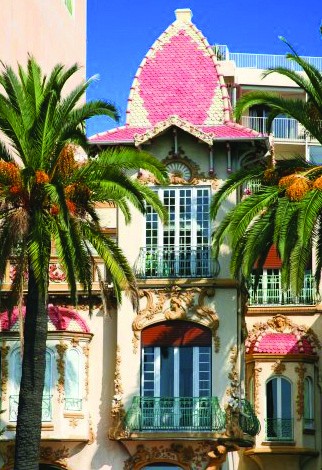

And build they did. The influence of Belle Époque architecture is ubiquitous in Nice, particularly in the Cimiez district, along the Promenade des Anglais and in Le Quartier des Musiciens. Indeed, if you allow your eyes to be drawn upwards, it is hard to avoid seeing the Belle Époque influence. When these magnificent properties were first built, the majority were painted cream and white so they would have stood proud in the sunshine – self-important, akin to giant wedding cakes. But now, one hundred or so years on, most of them have mellowed pleasingly and they create a certain ambiance of grandeur tinged with nostalgia.

Today, you can enjoy a walk in the footsteps of the Belle Époque’s winter visitors, “les hivernants”, and admire the flamboyance of their houses. There’s a self-confidence about the style which makes you wonder about the architects who were tasked with designing these ornate buildings.

In the early days, wealthy clients would go on personal recommendation, bringing in architects from Paris or abroad to interpret their vision of a winter palace. For example, the fabulous Villa Masséna (65 Rue de France), which is now a museum, was designed in a neo-classical style by the highly regarded Danish architect Hans-Georg Tersling, who had already worked for the Empress Eugenie and the Rothschilds.

However, as Nice became a more established destination, it was local architects such as Sébastien-Marcel Biasini and Charles Dalmas who made the greatest contribution to the eclectic Belle Époque style Niçoise. Biastini was responsible for the iconic, Palladian-inspired Crédit Lyonnais building (15 Avenue Jean Médecin), the Palais de Marbre (7 de l’avenue de Fabron) and the Villa Beau-site (17 Rue Mont Boron), commissioned by a wealthy British merchant.

Another grand commission was the Hotel Regina Excelsior in Cimiez, built with Queen Victoria in mind, and indeed she stayed there on three occasions with her staff of 100 and her statue still resides nearby. Although it was built on a monumental scale, the hotel still exhibits many of the characteristics we see in smaller buildings of the era, including lead-roofed cupolas on the corners, flamboyant stucco decorations and ornamental ironwork. Today, the building is converted into luxury apartments. Also by Biasini is the Villa of the Countess Starzynsky, an elegant yellow palace on the Promenade des Anglais

Another local architect, Charles Dalmas, came from more humble origins than Biastini, but his training in Paris at the Academie des Beaux Arts served him well and he built up his business steadily, ultimately completing around 100 houses, 20 or so hotels and other projects. Some of Nice’s most beautiful apartment buildings, such as the Hôtel Hermitage (Avenue Bieckert), the Winter Palace and the Grand Palace are the work of Dalmas. The Hôtel Atlantic (now the Boscol Exedra Hôtel, 12 Boulevard Victor-Hugo) and the Hôtel Le Royal (23 Promenade des Anglais) are just two of his fine hotel commissions. The Hôtel Plaza (Rue du Verdun), where he re-designed the facade, reflects the period fashion for elaborate stucco decorations.

Dalmas, more than any other, can be said to be the man behind much of the characteristic Belle Époque style present in Nice. As an architect of that era, his task was to interpret the sometimes fanciful whims and notions of his wealthy clients and create buildings which would not only delight but also harmonise with their surroundings. His demanding clients had seen some of the new architectural fashions during their travels to other European cities and resorts, but had also been introduced to exciting new design ideas at the magnificent Universal Exhibitions in London, Vienna and Paris. They wanted to indulge their taste for Italian and Classic influences, and also looked to incorporate Gothic, Moorish and Eastern decorative embellishments.

That is why each example of the Belle Époque style boasts so many individual decorative elements: the ceramics, frescos, friezes, ornamental stucco work, cupolas, decorative ironwork, faux stonework, figureheads, painted effects, garlands and grotesques. Clients wanted something of what they had already seen but flourishes which reflected their own personalities and tastes. For example, the mansion houses at 17 and 21 Rue Barla feature some beautiful mosaic decoration and painted friezes along their eaves, and the Palais Baréty on Rue Maréchal Joffre is notable for its bow windows and carved cattle heads, the latter reflecting the family business.

Sadly, many of the Belle Époque villas which once lined the Promenade des Anglais have not survived urban re-development. But at number 139, rudely squeezed between an Art Deco villa and a modern apartment building, you will be amazed to find the remaining part of the Villa Collin-Huovila, an example of pure Art Nouveau fantasy by architect Charles Marius Allinge which indulged the eccentric tastes of the Finnish millionaire who commissioned it.

Working on so many projects allowed Charles Dalmas to create a fusion of these influences and define a characteristic Niçois style, which he executed with increasing confidence as his career progressed. Today, it only takes a stroll around the centre of Nice to enjoy the special atmosphere created by these extravagant Belle Époque fantasy residences.

During the Centenary of the outbreak of World War 1, we should remember that the Belle Époque was named retrospectively – looking back from the 1920s to what appeared to have been an enchanted golden age. As they promenaded along Nice’s front or gamed at its casinos, the visiting playboys, princes and industrialists had little inkling of the coming horror of the war, which would bring an end to the party, claim millions of lives and destroy entire dynasties.

No building best illustrates this sombre postscript than the magisterial Hôtel Negresco, which overlooks the Baie des Anges. It was the personal vision of a Romanian named Henri Negresco, who envisioned that the fabulous pink-domed palace would tempt the very wealthiest to stay.

Having catered to the elite of European and American society, Negresco understood the tastes of the fabulously wealthy – so why would he not embark on this project fuelled with optimism? Alas, the hotel opened in 1913, one year before the outbreak of World War 1. Appreciation of the impressive architecture by Édouard Niermans was brief and wonderment at the extravagant interiors was short- lived. Tourism plummeted, the hotel became a hospital, was later sold to meet the demands of Negresco’s creditors and Henri himself passed away in 1920, aged just 52.

Originally published in the February-March 2014 issue of France Today

Guy travelled by train to Nice with thanks to www.voyages-sncf.com

More articles by France Today Editor-in-Chief Guy Hibbert

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *