The All-American Roots of the French Riviera

Madame Marianne Estène-Chauvin is a living, breathing embodiment of the Côte d’Azur. The proprietress of the Hotel Belles Rives, where Woody Allen’s recent Jazz Age romp Magic in the Moonlight was filmed, meets me after breakfast on her hotel dining terrace. Her orange nails are immaculate. Her purple jumpsuit was purchased a few miles away in Cannes. And her Art Deco jewellery harks back to the heyday of Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald.

As well it might. Because Estène-Chauvin’s family history is intertwined with the Fitzgeralds and the American invention of the French Riviera. After commanding a pot of Earl Grey (Madame’s handsome staff live in anxious awe of her) she settles down to dictate the story.

“It’s a classic tale,” she begins. “Like thousands of Russians, my grandfather Boma Estène fled the 1917 Revolution to America.” He got as far as the ocean liner port of Marseille. Alas, New York had to wait. For in 1922 he met the love of his life, Mademoiselle Simone Cohen, at a bus stop down the coast in Juan-les-Pins, then a sand-blown settlement between Antibes and Cannes. The Cohen family owned a small seaside pension and took lovestruck Boma on as a valet. He didn’t mess around. Six months later he had married young Simone and become the hotel accountant. It was then that the apparitions started.

Boma and Simone Estène began to see “strange people” on the sandy beach that links Juan-les-Pins with the peninsula of the Cap d’Antibes. “There were people bathing at midnight,” reports Estène-Chauvin. “And women without hats at lunchtime”. Strangest of all, at a time when local women wore black to mourn the 1.5 million Frenchmen killed in World War I, “these foreigners were dressed in colour and were showering money on meat and Champagne”.

The Sun Sets in the West

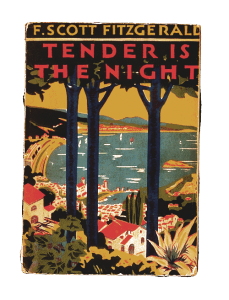

These “shouting and bawling” groups were Americans. They were using their powerful American dollars to flee the stuffy confines of Prohibition back home. Cole Porter played in American-owned cocktail bar Le Pam Pam. Fitzgerald rented Juan-les-Pin’s Villa Saint Louis in 1925 and scribbled a diary of the era that would become his seminal novel Tender Is the Night. Pablo Picasso captured the colourful bathing scenes of Cap d’Antibes’ Plage de Garoupe beach on canvas. His friend Man Ray snapped the same suggestive vistas on celluloid. For Boma Estène the business opportunity was as clear as the evening sunset over nearby Cannes.

The Fitzgeralds moved out of the Villa Saint Louis in 1926. Estène-Chauvin’s grandfather took the first train to Paris to meet with the villa’s owner, an elderly French widow. He proposed turning her rental property into a hotel. “It’s a crazy idea Boma”, she shot back. “French don’t like the seaside. And they don’t like mosquitos!”

But that wasn’t what Boma Estène had in mind. In 1929, on the site of the Villa Saint Louis, he opened the Hotel Belles Rives. Yes, it didn’t have the watersports club that sits below the hotel terrace today (where water-skiing was invented in the 1932). Nor the Fitzgerald Bar, where today’s signature cocktail is the Gatsby, a medley of Gin, lychee liquor and Perrier. And it only had one bathroom per floor. But American artists, writers and bon viveurs moved in en masse, each of them given a mosquito net on arrival. “And where celebrities go,” Estène-Chauvin tells me, “big money follows.”

courtesy of Hotel du Cap Eden-Roc

Americans Set their Presence in Stone

Stepping out from the Hotel Belles Rives, visitors arrive at a two-mile beach of golden sand. In the 1920s the same scene greeted Frank Jay Gould, the millionaire investor behind the Virginia Railway and Power Company. Back then the pine-scented coast between Juan-les-Pins and the Cap d’Antibes was just palms, fruit trees and sand. For Gould it looked like Miami Beach without the tourists. Priceless.

After snapping up the local casino, Gould build the Delano-style Hotel Provençal. With 290 rooms it dwarfed the Belles Rives across the street. Artistic elites moved out. High rollers moved in. Charlie Chaplin danced in the Provençal’s sprung ballroom (his movies were grossing millions in profit at the time). Winston Churchill, never short of a pound or two, gambled while chugging brandy and champagne. Luscious libertine Coco Chanel was turned away from the same casino for wearing ‘beach pyjamas’ – while on the beach itself women experimented with skirtless swimsuits. Moreover, in 1936 France’s socialist leader, Léon Blum, signed the warrant for two million French workers to take an annual paid summer holiday. This fusion of lefty ideals and capitalist allure funnelled thousands more into the bars of Juan-les-Pins, an American invention if ever there was one.

Alas, les années folles, those crazy days of sunshine, came crashing down in movie star style. Fifty-thousand posters advertised the inaugural Cannes Film Festival on September 1st, 1939. MGM charted an ocean liner carrying Gary Cooper, Douglas Fairbanks and Mae West to attend the event. But on the very morning of the gala opening Hitler invaded Poland. Just a single film, Charles Laughton’s The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, had been shown before France entered the war on September 3rd. The festival posters were replaced with ones calling for general mobilisation. The Riviera’s American dream went down in flames. And Gary Cooper’s boat steamed straight back home.

Ella Fitzgerald performing at Jazz à Juan in 1964. credit: Jazz à Juan

The Second Liberation

August 15th, 1944. American troops came ashore on St Tropez’s Plage Pampelonne. (The same beach is now a favourite of Jay-Z and Paris Hilton.) That day, tens of thousands more GIs swept ashore at a dozen other beaches on the French Riviera including the white sands of La Nartelle by Saint-Maxime and the silver swoosh of Rayol-Canadel-sur-Mer. This débarquement was part of the American liberation of France. In more ways than one.

I pick up one of Juan-les-Pins’ new Solex scooters to find out more. These two-wheeled, pressed-metal motos were first made in 1946. Now cult items, a new rental agency is offering lovingly renovated Solexes for tours of the Cap d’Antibes. The 49cc engine is powerful enough to get you from A to B – if you have a spare hour. You pedal to start the engine. And they have bike brakes on the handlebar. Yes. Bike brakes.

First I putter past the old Provençal Hotel, used by Allied troops after WWII. By the 1950s, Miles Davis and Sidney Bechet had the French rocking in its ballroom once again. Over in Cannes, which I can see off to my right as I cruise the Cap d’Antibes, stars like Tyrone Power and Errol Flynn sailed in to the inaugural spring Film Festival in 1951. Others arrived on Douglas DC-3s at Nice Airport, a spoke off the New York-Paris Lockheed Constellation overnighter. The biggest ship of all was the SS Constitution. It brought actress Grace Kelly – and half the world’s press – to her fairytale wedding to Prince Rainier in Monaco in 1956. American tourist dollars followed in quick succession. Even the advertising moguls on Madison Avenue could not have dreamt up a better PR blitz.

European Pleasures, American Leisure

Even Gatsby himself would be wowed by the Villa Eilenroc. I park the scooter at the pinnacle of the Cap d’Antibes where this endless Art Deco mansion commands an 27-acre, cyclamen-carpeted estate (and where real estate prices are around €35,000 per square metre). Belle époque visitors from maharajas to movie moguls were wowed, to say nothing of this awestruck writer. And I haven’t even been inside yet.

Tender is the Night by F Scott Fitzgerald

A Gatsby-esque American, Louis Dudley Beaumont, furnished the mansion with his beloved wife Hélène. There are club chairs and commodes, armoires and antimacassars. A first edition of Fitzgerald’s Tender is the Night sits on Beaumont’s private bookshelf in the main salon. That’s doubly wonderful, because the novel describes the champagne-soaked parties that took place in this very room. Outside the topiaried gardens slope down to the Mediterranean. Woody Allen’s Midnight in the Moonlight used this fragrant terrace for the scene of a midnight ball. Beaumont, Fitzgerald and guests went one step further, quite literally, by carrying the party down to the lapping waterfront where they carved a bar out of the Cap d’Antibes stone. Fortunately for us, Mrs Beaumont remained sober enough to gift the Villa Eilenroc to the City of Antibes on her passing in 1988. In hindsight, maybe she had been drinking…

Last Orders

In need of a drink myself I make a final pilgrimage to a fabled corner of American history. The Hotel du Cap Eden-Roc, the world’s most outrageously ostentatious guesthouse, sits next door to the Eilenroc. The Brad and Angelinas of this world take respite here during the Cannes Film Festival, where they recline on Louis XV chaises lounges and sip €25 Americanos. My drinks are on Philippe Perd, the hotel’s Managing Director, as he regales me with tales of times past.

“Americans love exotic destinations with historical links to their past”, says Perd. Although his hotel has played host to “crowned heads, politicians, artists and movie stars” such excess kicked off with a bohemian American family, Gerald and Sara Murphy.

Back in the 1920s the Eden-Roc, like all Riviera hotels, was a winter-only retreat for ageing Brits escaping the English weather. Beaches were for fishermen. Suntans were for farmers. However in 1923, the Murphys persuaded the hotel’s owner Antoine Sella, to stay open all summer. Their fancy dress beach parties enchanted Fitzgerald and Hemingway, plus other writers like Archibald MacLeish and Dorothy Parker, and enticed a generation of Americans to the glorious south. In a trice the summer holiday was born.

Perd is too gentlemanly to discuss hotel visitor numbers or today’s the current strong dollar. But it’s clear as another young American family bowls out of a limo – with a gaiety unknown to the Eden-Roc’s statelier guests – that the Murphys’ compatriots are back in greater numbers than ever before. (For her part Madame Estène-Chauvin confirms that American bookings at the Hotels Belles Rives are up 30% in 2015, a blessed relief from the ongoing crisis in France.) After reinventing the French Riviera in the 1920s, and saving it in 1940s, Americans seem set to perform the trick again.

DETAILS

Hotel Belles Rives: 33 boulevard Edouard Baudoin, Juan-les-Pins. Tel: +33 493 61 02 79. www.bellesrives.com Double rooms from €320.

Hotel du Cap Eden-Roc: Boulevard JF Kennedy, Cap d’Antibes. Tel: +33 493 61 39 01. www.hotel-du-cap-eden-roc.com Double rooms from €850.

Solex Scooter Rental: News Caffe, Palais des Congres, Juan-les-Pins. Tel: +33 649 40 52 89. www.so-solex.com Two hour guided tour €40.

Villa Eilenroc: Avenue Mrs Beaumont, Cap d’Antibes. Tel: +33 493 67 74 33. www.antibesjuanlespins.com Open Wednesday and Saturday 1-4pm (3-7pm from July to September). Entrance €2.

The Hotel Provençal was purchased in 2014 by British tycoon John Caudwell. It will reopen as a luxury apartment complex towards the end of the decade.

Based in Nice, Tristan Rutherford has been a freelance travel writer since 2002.

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in cote d'azur, Fitzgeralds, French Riviera

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *