Monument Man: Exploring Mâcon, Birthplace of Alphonse de Lamartine

On the 150th anniversary of Alphonse de Lamartine’s death, Marion Sauvebois unspools the life of the beloved poet, national hero, abolitionist and enduring enigma, whose passing sparked a furious race for the privilege to host his memorial

Throughout his life Alphonse de Lamartine made a noise– and even in death he didn’t go quietly.

His corpse barely room-temperature, an all-out bidding war broke out over which city would get the honour of hosting the national treasure’s official memorial statue. Two days after his passing on February 28, 1869, canny Paris got a head start, kicking off France’s first-ever crowdfunding campaign – pipping his birthplace of Mâcon to the post by 72 hours. Rightly peeved, his fellow Mâconnais struck back with a rival pledge drive, urging every man, woman and child to dig deep. This was a battle fought on doorsteps, with leaflets, goodwill and, no doubt, a great deal of arm-twisting. By December, the humble Burgundian nook had raised 55,204 Francs to Paris’s 20,000. The capital grudgingly bowed out. Lamartine was heading home.

Head to the poet’s birthplace of Mâcon for breathtaking riverside views

THE MAN, THE MYTH

“He has an undeniable aura about him,” says my guide, Claire, as the hotly-contested statue finally comes into view. Pen poised, eyeline set on the horizon, our bronze-hewn hero stands sentinel on Mâcon’s riverbank, journal in hand, dreaming up his next cause célèbre.

It’s all I can do to stifle a pang of disappointment at the sight of the rather plain (if fetchingly silhouetted against the setting sun) rendering.

This is the monument that launched a thousand door knocks? But who am I to argue with the good folk and tastemakers at the École des Beaux-Arts?

Portrait ofAlphonse de Lamartine by Henri Decaisne. Credit: MUSÉE DES URSULINES DE MÂCON

A revered and hugely-prolific Romantic poet, political maverick, voice of the oppressed, abolitionist, journalist, acting President… Lamartine was a living legend. And not immune to stoking his own mystique.

He was also, well, just a man. A father beset by tragedy, who lost his two young children (and later his wife) to tuberculosis; an inveterate gambler (everyone agrees); an adulterer with a litter of illegitimate bairns (now that depends on who you ask: women tend to lean towards yes, men dismiss it as utter poppycock); a charitable soul who paid for his beneficence with dire poverty.

Digging into his past is akin to being yanked down a rabbit hole of ‘he said, she said’. The deeper you delve into the meanders of his life, the more elusive the man.

“He was complex – and very hard to pin down,” concedes Claire, craning her neck to catch one final glimpse of the barely discernible monument, his sharp features a blur in the fading light. For all its simplicity, there is, I realise, something aptly inscrutable about the unassuming statue. “One thing is certain,” she chuckles warmly. “Two cities fighting over him: he would have loved it.”

THE PHILIPPES

There’s no swifter way to puzzle out the man from the myth than a quick powwow with Philippe Sornay and Philippe Mignot, or “the Philippes” as they are known locally, in the very places that stirred Lamartine’s imagination and deep-rooted sense of (in)justice.

The respective owners of his childhood home in Milly-Lamartine and the Château de Saint-Point, just a stone’s throw from Mâcon, are self-appointed custodians of the radical’s rich legacy – and good name. They both stand firm in their belief that the Father of Romanticism was far from the philanderer most would have him be. And they have endless counter-arguments to set tattle-tales right.

Rumour has it Lamartine embarked on a torrid affair with the owner of the Château de Pierreclos. Photo: Shutterstock

Of course, if you are chomping at the bit for the dirty deets, take a detour via the Château de Pierreclos – a marvel of Burgundian glazed roof-tiles – where vigneronne Anne-Françoise Pidault has no qualms about regaling guests with the juicy particulars of his (alleged) trysts. In fact, a whole panel in her B&B’s small museum recounts how the young poet fell head over heels for the lady of the manor and embarked on a passionate dalliance with the married woman, who reportedly bore him a child. When I point out to her that Messieurs Sornay and Mignot vehemently deny the affair, she chuckles: “If the Philippes say so – I wasn’t there!”

Snug amid vineyard-studded Mâconnais, La Maison d’Enfance (childhood home) de Lamartine is a rustic pied-à-terre without airs, its only standout feature sheets of cascading ivy. This, I discover, is a late addition, courtesy of Lamartine’s indulgent mother. In a bout of poetic licence, it appears the bard had waxed a little too lyrical about the evergreen leaves shimmying up the family seat’s façade, prompting raised eyebrows from visitors faced with a bare stone frontage on arrival. Keen to salvage her son’s honour, his dutiful maman got planting to keep the fantasy alive. Few mementos of his life here remain, besides a set of octagonal dinner plates and the odd portrait, the bulk of his possessions having been sold off to repay mounting debts long before his death. One crucial tradition subsists, however.

Philippe Sornay, whose family has owned Lamartine’s

Maison d’Enfance for seven generations. Photo: Marion Sauvebois

“Lamartine’s mother welcomed the misery of the world into her home,” Philippe Sornay explains. “She devoted her life to helping others and encouraged him to play with the local children so the front door was always left open. And we carry on the tradition. I have stayed faithful to the spirit of Lamartine and his open-mindedness,” he adds with obvious pride.

“The door opens out onto the outside world, everybody is welcome.” He credits this open-door policy as the “foundation of Lamartine’s politics”, fuel for his sensitivity to the plight of the less fortunate and the bedrock of his egalitarian views. His mother also seemingly drilled into him a lasting sense of respect for the fairer sex. Decades ahead of his time, he would go on to champion education for women and even founded a girls’ school. That being said, he drew the line at their right to vote…

The gate of Lamartine’s childhood home remains forever open

“The leading thread of his career and life was how to improve the living conditions of the people. And he lived what he preached.” He trails off before adding with disarming conviction: “He wasn’t quite the spendthrift people made him out to be. But he was generous to a fault and gave away far more than he had. As the only male heir, he inherited everything but made sure his sisters never wanted for anything. And he would give away priceless heirlooms to locals as wedding gifts or when they needed money – that’s why there is not much left in the house. He couldn’t stop himself. His generosity was his downfall. In the end, he was left with nothing.”

Racked with debts, the poet had to part with his childhood home

in Milly-Lamartine. Photo: Marion Sauvebois

This “hellish downward spiral” is how Philippe’s family came to acquire the Lamartine homestead in 1861. By then, racked with debts and reduced to truly dire circumstances, the disillusioned politician was forced to part with his childhood home – a heartache he described as akin to “selling the marrow from his bones”. Loath to let it fall to strange hands he begged a friend, Philippe’s ancestor, to purchase it. Moved by Lamartine’s pleas he eventually relented, agreeing to take it on temporarily, until such time as the impecunious poet was able to buy it back. Lamartine never did.

“We’ve passed on this torch through the generations, to preserve and share his legacy, preserve the soul of Lamartine in this house. He’s still here,” Philippe S. insists. “I want people to feel what this house meant to Lamartine.”

The Château de Saint-Point. Photo: Marion Sauvebois

LIVING MUSEUM

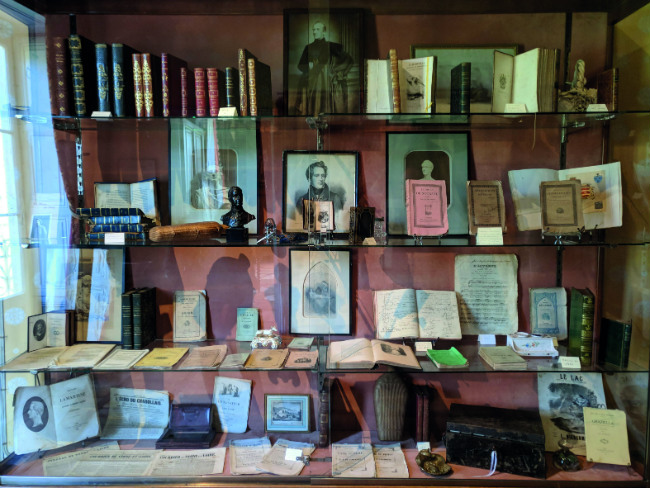

While Milly-Lamartine holds precious few remnants of Lamartine’s existence, Saint-Point is a vast time capsule and a wall-to-wall shrine to the politician and poet.

His office upstairs has remained virtually untouched, shelves groaning under the weight of his oeuvre – owner Philippe Mignot’s ever-growing library includes countless first editions of his tracts, poetry collections, essays and histories – while the living room is flanked on all corners by display cases heaving with relics of his political, literary and love life.

Among them are the neckerchief reportedly worn by his first love Graziella, a Neapolitan fisherman’s granddaughter whom he immortalised in his 1852 eponymous novel, and the tattered Tricolor flag (dug up from a mound of dust-coated memorabilia in the attic) Lamartine bravely waved in a tense standoff with baying republicans, eventually convincing them not to replace it as the emblem of the nation.

Lamartine saved the Tricolor flag. Credit: MUSÉE DES URSULINES DE MÂCON

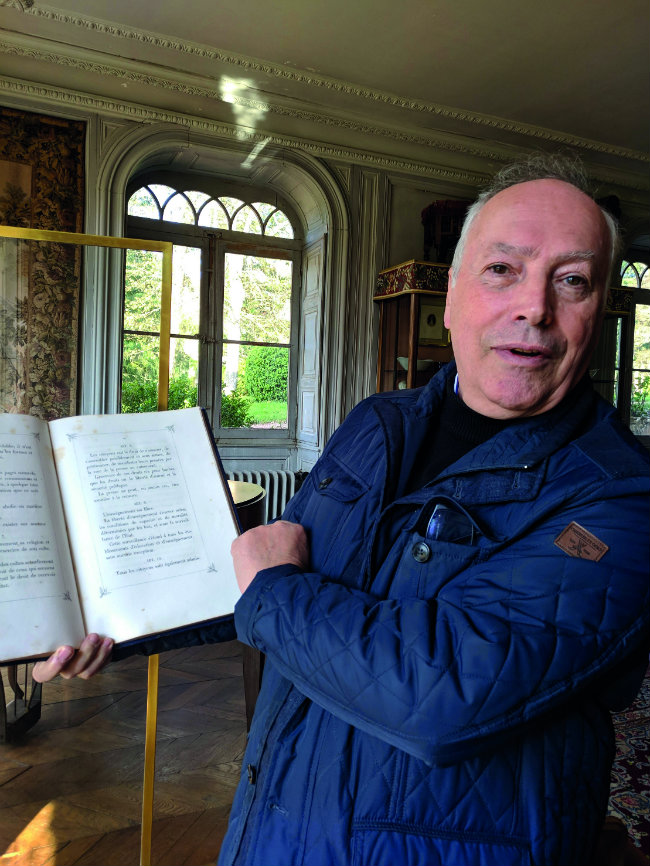

Like his namesake, Philippe M. speaks with such affection, hushed reverence and insight, it’s near impossible to believe he’s not descended from the man himself – or indeed a bona fide Lamartine scholar. But by his own admission, until he bought the château 15 years ago, he was a “Lamartine novice”. Undaunted, he wholeheartedly embraced his “duty of memory”, genning up on the republican hero and restoring his Neo-Gothic pile to its former glory.

“After Lamartine’s death and burial on the grounds, his niece Valentine set out to turn the château into a mausoleum of sorts. But by the time I moved in most of his belongings had been stashed away, historical artefacts jumbled together with worthless tat and keepsakes in the attic,” he chortles at the recollection. Despite his protestations to the contrary, Philippe M. has become the undisputed local Lamartine authority – the mere whisper of his name enough to categorically settle any debate or swat away hearsay. And he’s quite the raconteur too…

The Château de Saint-Point is a shrine to the poet. Photo: Marion Sauvebois

“It is from this very place that he imagined a better society,” he sets the scene. “Lamartine laid down the foundation of modern democracy and reshaped the human condition – not only in France but across Europe and in the United States too – but ultimately ruffled too many conservative feathers…” But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. After a spell as a diplomat in Naples, he was elected as an MP, all the while enjoying major success as a poet with the release of his Méditations Poétiques.

But it’s his decisive role in the 1848 Revolution that marked the peak and eventually untimely end of his time in office. Following the overthrow of King Louis Philippe in February of that year, Lamartine was called upon to head up the Provisional Government. But not everyone approved of his populist agenda or, for that matter, his fundamental reshaping of democracy. Despite being, on the face of it, the opinionated voice of the new government, he was forever relegated to the sidelines: suspiciously left-leaning for his right-wing peers; the shadow of his conservative roots an insurmountable obstacle for liberals.

Château de Saint-Point’s owner Philippe Mignot. Photo: Marion Sauvebois

No matter. During his brief three months in power, he fast-tracked every motion he’d so far been unable to push through parliament. He abolished slavery and the death penalty as a political weapon and rolled out universal male suffrage, paving the way for the first democratic presidential election – which he, ironically, lost to Louis Napoleon, a dictator-in-waiting who three years later ditched the (second) republic and appointed himself emperor. Though by that point a disillusioned Lamartine had long since retired from politics. This chapter of his life firmly behind him, he became “a slave to writing”, working manically to keep creditors at bay. But no amount of royalties could haul him out of this financial quicksand.

Stout-hearted until the bitter end, he passed away two years after suffering from an apoplexy attack (a stroke). “He is gone but not forgotten,” Philippe M. absent-mindedly punches the air. “He was flawed like everybody else, but he was fiercely loyal and brave. He never lacked the courage of his convictions. He is one of those men who counted.”

A monumental man worthy of a fitting monument.

The inauguration of Lamartine’s memorial statue. Credit: Musée des Ursulines de Mâcon

MÂCONNAIS ESSENTIALS: WHERE TO STAY AND EAT

Hôtel Le Panorama 360 Spa & Skybar

4 rue Paul Gateaud, 71000 Mâcon

www.hotelmacon-panorama360.com

Le Poisson d’Or

Allée du Parc, 71000 Mâcon

www.lepoissondor.com

L’Ô des Vignes

129 rue du Bourg, 71960 Fuissé

www.lodesvignes.fr

Château de Pierreclos

71960 Pierreclos

chateaudepierreclos.com

Musée des Ursulines

THE SAGA CONTINUES…

Make a beeline for Mâcon’s Musée des Ursulines for a blow-by-blow account of the town’s face-off with Paris, the ensuing argy-bargy about where on home turf to erect the monument, and the hotly-contested design competition. A whopping 27 sculptor-architect teams threw their hat in the ring for this commission of a lifetime. Sculptor extraordinaire Alexandre Falguière won and wasted no time in fine-tuning his mock-up. Yet, upon closer inspection, many found the statue only bore a passing resemblance to the great man. So a sheepish Falguière was marched back to the studio for last-minute tweaks – until Lamartine’s niece and friends were satisfied he’d created a perfect likeness. The museum unveiled a shiny new wing dedicated to Lamartine’s life and times on July 20.

From France Today magazine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY

REPLY