Hidden France: Memories of the Resistance in the Gers

More often than not I’ve found that detours can enrich our journeys, altering us in unexpected ways. I often take the roads less travelled, choosing the unpredictable instead of being tethered to a map. Such was the result recently after deciding to return home from a friend’s house in the southeastern corner of the Gers, along the green-carpeted hills of the Lannemezan plateau, which borders the foothills of the Pyrénées.

After manoeuvering a hairpin curve through an unexpected pocket forest, I noticed the glint of a small white sign in front of an open gate that read: Historic Monument – Maquis de Meilhan. Ahead of me, an elderly couple had left their parked car and were slowly making their way along a white-fenced footpath up a steep hill. Curious, I parked my car and discreetly followed them. The monument comprised two small farmhouses, a memorial tower, a cemetery and a sculpture commemorating the bravery of 76 men, ages 17-70, who died in a battle that took place on the nights of July 6th and 7th 1944 between a band of Maquis, the collective name given to French Resistance fighters of WWII, and a battalion of 200 Nazi soldiers. I was confused. I’d always thought the Gers was in the unoccupied zone during WWII. So I decided to ask my circle of local friends.

The Castelnau-sur-l’Auvignon memorial. Photo: Sue Aran

Parachuting into France

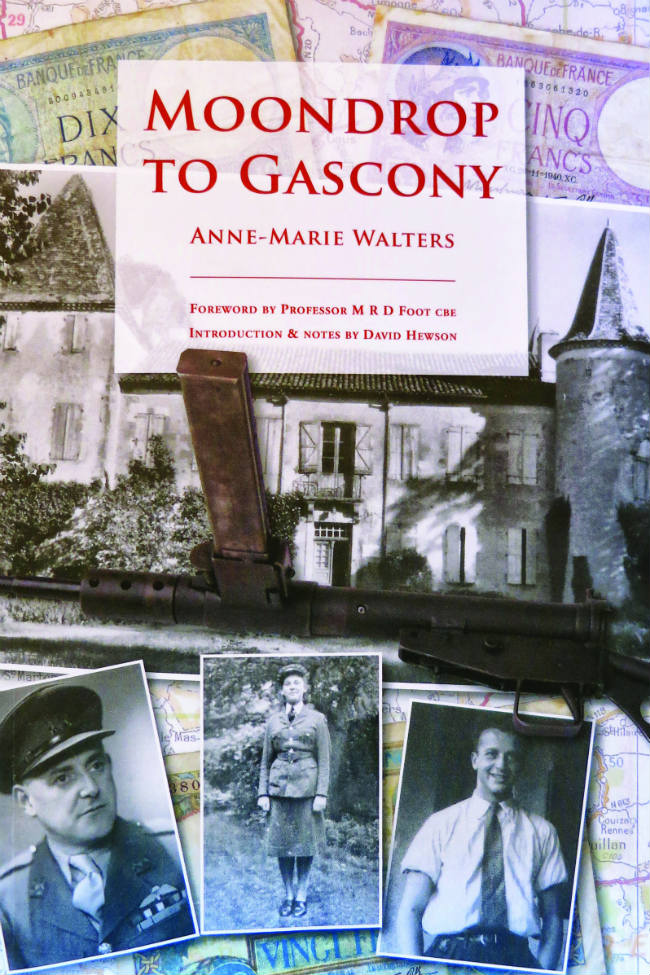

Jacqueline Aranzasti, a retired Air France stewardess and member of the local historical society, recommended a book called Moondrop to Gascony, the riveting, first-person memoir of Anne-Marie Walters, then a 20-year-old British secret agent. Parachuting into southwest France in 1944 to work with the Resistance in preparation for the impending Allied Invasion, she acted as a courier for George Starr, then head of the Wheelwright Circuit, one of 54 networks of the Special Operations Executive (S.O.E.), part of Britain’s nine wartime secret service agencies during WWII. Earlier, Winston Churchill had established the S.O.E. in order to wage a secret war on the Continent in an effort to thwart Hitler’s push across the English Channel. Over seven months, Anne-Marie traversed the region, carrying messages, delivering explosives, arranging the escape of downed airmen, and receiving parachute drops of arms and money in the dead of night. She lived in constant fear of capture by the Nazis.

Madame Lalanne, now aged 96: “I remember “I remember the Nazis coming to the door and pounding on it

with the butts of their rifles.” Photo: Sue Aran

The Liberation of France

Many of the villages I’ve frequented, marketed in and photographed over the last 10 years were mentioned in her book as being instrumental in the liberation of France. A much bigger picture of the area I now called home was emerging, as well as more questions.

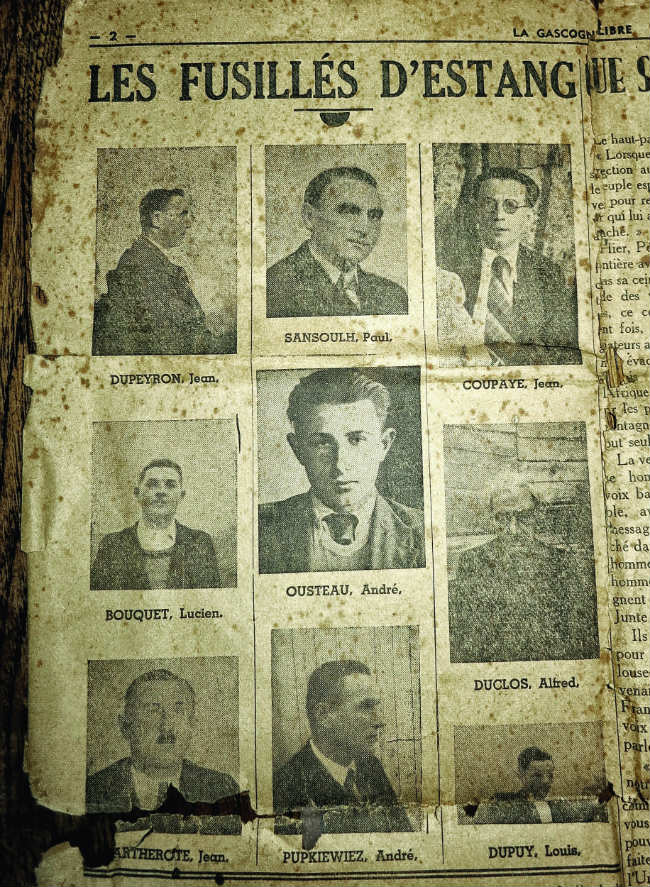

Pierrette Lalanne is president of Agora, a small group of volunteers with whom I work to promote cultural events in the village of Estang. I asked if she knew anything about the Nazi occupation in this area. Overhearing us, her mother, beautifully elegant at 96 years of age, walked through the kitchen door with a folded, yellowed newspaper. Pierrette opened it gingerly and exclaimed, “Maman, I’ve never seen this! Where were you hiding it?” The newspaper recounted the deaths of nine local men, pillars of the Estang community, who were shot in reprisal for Nazis recently killed by the local Maquis.

Madame Lalanne shrugged and sat down. After a pause she said, “I have many memories. I remember the Nazis coming to the door and pounding on it with the butts of their rifles. My young son stood by the door when I opened it holding a toy riding crop. The Nazis took it from him and he was very upset. They searched the house looking for rifles. Fortunately, they didn’t find any, though some were hidden in the attic. After they left I ran to the vineyard to find my husband, but the Nazis arrested me. I was let go later in the day, but I never knew why. They started to burn houses at random but gave up after it began to rain.” Lost in memories, Mme. Lalanne became quiet. I thanked her for speaking with me.

newspaper account of the nine men from Estang who were executed in reprisal for the deaths of Nazis

Consulting history books about WWII, I learned that even though the Treaty of Versailles was signed between Germany and the Allied powers on June 28, 1919, bringing an official end to World War I, provisions in the Treaty led to a state of chaos within Germany that allowed the Nazi Party and Hitler to rise to power. By the autumn of 1939, Hitler had successfully intimidated his western neighbours and invaded Poland. In solidarity, Britain and France declared war on Germany. Subsequently, Philippe Pétain, the French military hero of WWI, became the authoritarian head of France, controversially signed an armistice with Germany and moved the capital to Vichy, dividing the country into occupied and unoccupied zones, with what would be dire consequences.

The War Memorial at Estang. Photo: Sue Aran

By 1941, a collaborative faction of the French police, La Milice, had begun to round up and incarcerate thousands of Jews, gypsies, homosexuals, intellectuals, immigrants, and political dissidents. All over France, resistance groups began to form. The people of the Gers were especially hostile to the Germans: too many of their young men had died in WWI defending France from Germany. Throughout history, the Gersois had been victims of fluid borders and royal chess games. Now they were uniquely ripe for the important role they would play the liberation of France. In 1942, the Nazis moved to occupy the remaining free parts of France. The following year, all resistance groups were organised under one umbrella organisation – which brings us back to Anne-Marie Walters, George Starr and my next conversation.

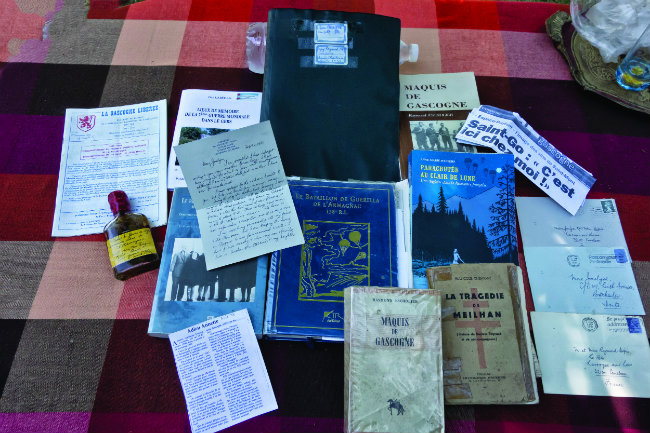

Vincente Carerre, wife of Guy Carrere, whose parents’ house was among those burned by the Nazis in the village of Estang, is an authority on the history of this area. Vincente suggested I speak to Jocelyne Sampietro. The following afternoon she and her husband, Jean-Jacques, welcomed me to their 300-year-old estate near the fortified medieval village of Larressingle, eager to share what they knew. Jocelyne’s parents were vital to the effectiveness of the local Resistance. Born in 1941, Jocelyne doesn’t remember much first-hand, but she had collected documents, photographs, books and newspaper clippings for her son, so that he would never forget what had happened.

Jocelyne Sampietro, whose parents fought in the Resistance. Photo: Sue Aran

“After the occupation moved south we had very little to eat,” she explained. “The Nazis took everything for themselves. But my parents gave refuge to Jewish families trying to escape over the Pyrenees, as well as to two British pilots, whose plane was shot down nearby. They also hid local youths who refused conscription to the Nazi workforce. They knew Anne-Marie Walters and George Starr. In fact, they hid arms later used in the Wheelwrights’ battle at Castlenau-sur-l’Auvignon. After the war, Nazi prisoners were billeted to work on local farms. Years later, those who had worked for my parents came back to thank them for the kindnesses they’d been shown. The Resistance took its noblest form in the simple acts of good people, like my parents.”

some of the collection of documents belonging to Jocelyne Sampietro. Photo: Sue Aran

A few days later I drove to Castelnau-sur-l’Auvignon, once the secret headquarters of George Starr. Flowers shimmered everywhere in the quiet hilltop village, itself a memorial to the aforementioned battle. Led by written explanations and photographs posted along the main street, I learned that a force of 150 Resistance fighters were confronted by some 2,000 Nazi troops. Fierce fighting ensued and the village was ultimately bombed into rubble. Starr and his fellow survivors dispersed and later regrouped some 60 kilometres southwest, in the village of Panjas, where I spoke with Christiane Couerbe, a gentle, elderly woman who carries the memories still. Shortly after my arrival we were joined by Michel Lafargue, a 90-year-old friend of hers, also a survivor, who interrupted occasionally to correct her. I listened intently as she recounted the story from notes she had carefully written.

Christiane Couerbe. Photo: Sue Aran

“At that time all of the remaining Maquis in the Gers joined forces with Colonel Maurice Parisot, leader of the Panjas Armagnac Battalion. Col. Parisot learned that the Nazis had just arrested eight Jews in the village of Cazaubon, a few kilometres north of Estang. In retaliation he and his men carried out an attack. They fought fiercely for several hours and eventually scattered into the surrounding forests. That battle symbolized the beginning of the liberation of the Gers.”

At the end of our conversation Michel asked me where I lived. When I answered him, he asked if I knew Maurice de Mandelaire, and I said I did. Maurice owns the Domaine de Saoubis, a renowned Armagnac distillery built by his parents, just across the main road from my house. Michel told me Maurice’s father was known in the Resistance as “Raoul le Belge”.

Michel Lafargue shares memories of WWII. Photo: Sue Aran

Recruited by the Resistance

“My father came from Belgium and was fluent in German and French. He was very clever. When Belgium fell to Germany he fled south and was soon recruited by the Resistance. Acting as a liaison he often donned a Nazi uniform to secure supplies for the Maquis. All the Resistance fighters risked their lives for freedom and to restore the honour of France. It was here he met my mother and it was love at first sight.” Maurice’s eyes sparkled. “They married and took over this property where she was born. If not for the War, I wouldn’t be here!”

Until recently, I was unfamiliar with the history of the Resistance in the Gers. Having grown up in the United States I have enjoyed a life of relative peace and stability, free from despotism and authoritarian rule. But the world is changing and these fundamental rights are being challenged, both in the United States and abroad. We must therefore pay heed to the excesses of the past in order to avoid succumbing to the popular demagogic temptations of the present. Freedom is incredibly fragile.

The memorial at Panjas, home town of Christiane Couerbe and Michel Lafargue. Photo: Sue Aran

Travel Essentials

Memorials of WWI and II dot the Gers countryside. For a comprehensive map please contact: The Department of Tourism for the Gers and The Auch Resistance and Deportation Museum

Books of Interest

A Train in Winter by Caroline Moorehead

Fighters in the Shadows: A New History of the French Resistance by Robert Gildea

Moondrop to Gascony by Anne-Marie Walters

Village of Secrets by Caroline Moorehead

From France Today magazine

The Memorial at Meilhan commemorates 76 men who died in a battle between a band of Maquis and a battalion of Nazis. Photo: Sue Aran

“Moondrop to Gascony” by Anne-Marie Walters

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

By Sue Aran

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY