Why Go Now: Normandy’s Third Impressionist Festival

The theme for Normandy’s third Impressionist Festival, which runs for five months between April 16 and September 26, is Portraits. Its two previous events, held in 2010 and 2013, revolved around painting en plein air (outdoors) and water, both central to the Impressionist movement.

Les dahlias, jardin du Petit Gennevilliers by Gustave Caillebotte (1893)

This year’s focus comes as something of a surprise, as Impressionism is generally regarded as a style practised outside the studio, due to its preoccupation with the effects of light shifting over land and sea. But the strength of the festival, and the reason why anyone with more than a passing interest in Impressionism should book a ticket now, is its layered approach to a movement so fluid and variable that, like the moods and light it tried to capture, it remains impossible to pin down.

One of the beauties of the Normandy Festival is that it seems to be learning and discovering as it goes along. As the triennial programme widens in scope and builds on preceding years, adding dozens of new venues and events, the festival also tries to tease out unexplored threads in Impressionism and deepen our understanding of what it was, who its major and minor players were, the breadth of its influence and what it tried, in all its many offshoots, to achieve.

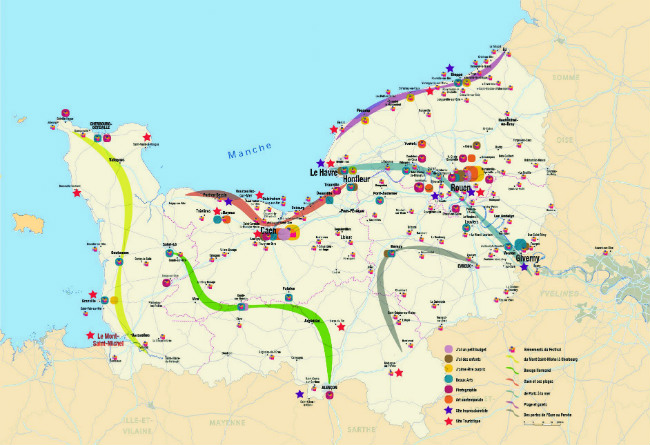

Map depicting the events of the Normandy Impressionist Festival

A Multimedia Event

The whole of Normandy, from major towns to tiny medieval villages, has been galvanised for the festival with a huge calendar of cultural events, including 15 major exhibitions and scores of related shows of contemporary art, photography, dance and music, theatre and cinema, plus conferences and lectures. More light-hearted events include a guinguette – the riverfront cafés popular in the 19th century, with accordion music and dancing (Parc de Clères) – several déjeuners sur l’herbe picnics (Touques, Avranches), and a recreation of an Impressionist-style wedding (Château Coisy, Hénouville). On the music side, besides a programme of Impressionist music, the Opéra de Rouen Normandie invites you to interpret Proust’s legendary Vinteuil Sonata, from Remembrance of Things Past, by rearranging samples from the festival theme in a dedicated app created by NoMadMusic.

The festival’s richness and diversity point to its real overarching theme: for a movement with no manifesto to rally around, no organising principle, not even a name until a dozen years after Monet began his explorations into temporality and light (and then only by happenstance), Impressionism’s influence was, and still is, immeasurable.

Eugène Boudin, Maree basse a Etaples, 1886. Bordeaux, musee des beaux-arts

Deep Normandy Roots

Normandy and Impressionism go hand in hand. Besides spawning its greatest star, Claude Monet, and his mentor and lifelong friend, Eugène Boudin, the region’s tremendously varied landscape, covering miles of beaches, picturesque cliffs, ports and fishing villages, the meandering Seine River and vivid green rolling farmland, was an inspiration for budding Impressionists and for some of their major precursors: Constable, Turner, Géricault, Courbet, Corot.

Raised in Le Havre, Monet was making his living as a caricaturist in Paris when Boudin, 16 years his elder, urged the teenaged prodigy to come back to Normandy and focus on something more worthy of his talent. The Honfleur native took Monet out on painting excursions, introducing him to the exquisite play of light over the Le Havre harbour and Seine estuary and the glories of the Normandy landscape. Monet was hooked.

It wasn’t long before other artists joined in, and the band of merry painters – which included Monet’s other mentor, the Dutch painter Johan Barthold Jongkind, along with Courbet, Sisley, Daubigny, Bazille, poet Charles Baudelaire and a half-dozen others – were hanging out at Honfleur’s thatch-roofed La Ferme Saint-Siméon inn (now a luxury hotel), eating and drinking under the apple trees, arguing and laying down the first principles of Impressionism.

Eugène Boudin, La Plage de Trouville, 1867. Paris, musee d’Orsay

Taking painting out of the studio – with the help of newly invented synthetic paints in portable tubes – was just one Impressionist innovation. Dispensing with the constraints of academic painting – clearly delineated lines, formal perspective, eventually the solid object itself – was another. But none of this happened overnight. In response to a time of immense social and intellectual change, the movement’s evolution was rapid and surprising yet also slow and steady, with an ever-revolving cast of characters from many countries experimenting with this new-found freedom.

While the Impressionists may be most famous for their invention of the modern landscape, they also revolutionised other forms of representation, particularly the portrayal of the face and body. Along with the attempt to capture light and weather played over a landscape, these artists, working as a loose but interconnected group, tried to portray people in their close surroundings as if glimpsed for a fleeting moment– a subjective response to a scene unfolding in time; transient gestures caught forever on canvas yet conveying the ephemeral.

Rouen Fine Arts Museum

A Time of Social Change

As new modes of transportation afforded more mobility and new recreations, and commerce began to loosen class boundaries, social life in the 19th century was undergoing enormous transformations. The Impressionist interest in capturing life as it was truly lived naturally meant depicting interiors – meeting places, familial homes, even theatre and opera performances and café society – which were recorded in sketchbooks and elaborated in the studio. Using mistresses, wives, children and friends as models and painting them as they went about their daily lives brought an intimacy, immediacy and a profound psychological dimension to their work.

Of the central exhibitions, Manet, Renoir, Monet, Morisot: Scenes of Impressionist Life (until September 26), at the superb Musée des Beaux-Arts Rouen, elaborates most comprehensively the human element at the heart of this year’s festival. Laid out in ten themes – artistic identities, muses and models, childhood, etc. – the exhibit explores the many facets of the artists’ intimate lives through paintings, drawings, sculpture, letters and photographs.

Méditation. Mme Monet au canapé (Claude Monet, 1871)

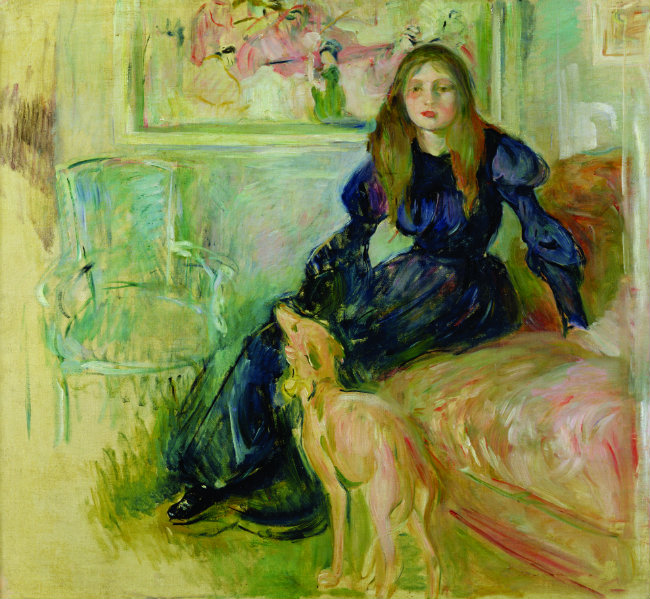

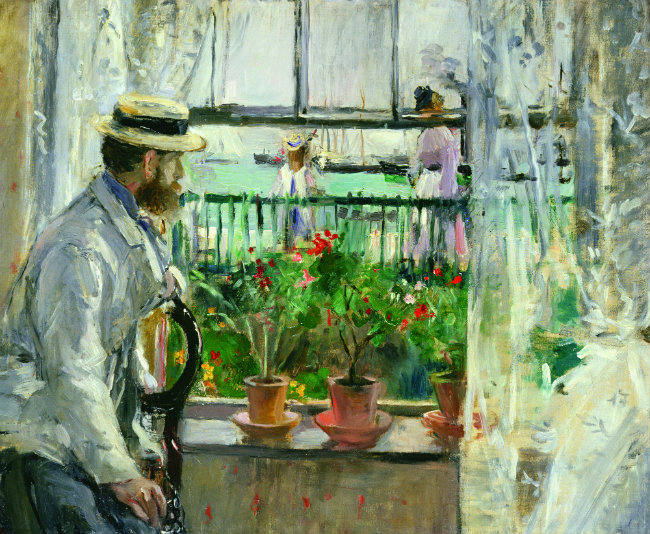

As viewers meander through the show a surprising picture of just how intertwined the artists’ lives could be – sharing models, teachers, dealers, sometimes studios – begins to emerge. In the section Jeunes et Julie, the young Julie Manet is represented from infancy to adolescence in portraits and depictions of the family environment by her mother, the brilliant Berthe Morisot, her uncle Édouard Manet (Morisot was married to his younger brother, Eugène) and their close friend Auguste Renoir.

It’s easy to see why critics of the day considered Morisot the leading Impressionist painter. Her portraits of Julie and scenes of intimate family life, both indoors and out, achieved using her characteristic deft, rapid brush strokes, resonate with intensity and emotion.

Morisot was one of four major female figures of the Impressionist movement. The others – American painter Mary Cassatt, Marie Bracquemond, a student of Ingres, and Eva Gonzalez, the only student Manet ever accepted – were instrumental in furthering the Impressionist exploration of the private realm behind closed doors. But familial life was not at all the sole domain of the female Impressionists. Among the many great works in the show, Monet’s Méditation (1871) shows his young wife Camille (who posed for several other Impressionist painters) in repose on a divan, lost in thought, a closed book in hand. A tender moment made more poignant by the contrast with his impassioned painting Camille on Her Deathbed – a flurry of white brushstrokes like a bridal veil shrouding his wife’s grey face, made only eight years later but showing an enormous contrast in style and gesture.

Julie Manet et sa levrette Laërte, by Berthe Morisot (1893)

Musée d’Art Moderne André Malraux (MuMa) in Le Havre

Intimacy in the Landscape

Another of the festival’s major shows revisits the work of Monet’s mentor Eugène Boudin in a sweeping exhibit at the wonderful Musée d’Art Moderne André Malraux (MuMa) in Le Havre. Eugène Boudin: Atelier of Light assembles more than 325 works by the pioneering painter from galleries worldwide to complement the museum’s own extraordinary collection. The exhibition underscores the great painter’s enormous influence on the Impressionists in both landscapes and in his attention to social conventions of the time.

In the early 1860s, Boudin began including people in the beach scenes he was painting around his native Honfleur and in nearby Deauville, Trouville and Le Havre, where well-to-do Parisians – freed to travel to the seaside by the new passenger train lines– would gather in their finery for a day on the beach. Boudin’s mastery of ephemeral details in these paintings, done over a three-year period between 1860 and 1863, presage the next 20 years of Impressionist endeavor: a passing breeze captured in a fluttering silk shawl, sunlight filtered through a parasol, the dappled shadows of clouds passing overhead… these were just a few of the effects Boudin employed to convey both an intimacy of the moment – people interacting in their daily life – but also a reflection on ephemerality and transience that captures an essential, timeless quality.

However, Boudin abandoned the project, discouraged by the paintings’ reception by the very people he was painting. They did not like his portraits of them – quick dabs of colour without focusing on individual likenesses – preferring something a bit more realistic.

Thaulow, La Rivière Simoa l’hiver, 1883, Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo

Far-Flung Influences

The revelation of this year’s festival, Frits Thaulow: Landscapist by Nature at the Musée des Beaux-Arts Caen, introduces the great Norwegian painter in the most comprehensive retrospective of his work ever mounted. One of the most important European landscape artists during the Impressionist period, Thaulow lived and studied in France for ten years and was tremendously influenced by Monet and Impressionism, but developed his own characteristic style that focused on the grandeur of nature. A brilliant colourist, Thaulow’s work establishes the painter’s exquisite gift for portraying movement, reflections of light on water or a snowy landscape (a genre he loved), and at dawn or twilight.

If you can’t make it to Caen, you can always take your consolation at the excellent Musée des Impressionnismes in Giverny, whose Caillebotte: Painter and Gardener revisits the great chronicler of Haussmann-era Paris in his lesser-known riverscapes and landscapes and gorgeous garden scenes, all of which are a joy to behold. Set in the grounds of Monet’s home and garden, the excellent museum café makes it easy to spend a delightful day there.

DETAILS: All of the major shows close with the festival on September 26, but dates of smaller shows and their performances vary. A detailed schedule of events can be found at www.normandieimpressionniste.eu including a map of participating towns and suggestions for 12 circuits with connected themes.

From France Today magazine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY