Grand Designs: Le Corbusier, the 20th Century’s Most Influential Architect

His concrete monoliths still divide opinion today, yet Le Corbusier is undoubtedly the most influential architect of the 20th century. Ulrike Lemmin-Woolfrey investigates

Father of modern architecture, Le Corbusier was a true trailblazer. He was a contemporary and friend of Picasso and Dalí, who met Einstein and became infatuated with Josephine Baker. A man who travelled the globe, crossed the Atlantic in the Graf Zeppelin, and flew across South America with Saint-Exupéry. A man who once skinned his dead pet dog and then covered one of his books in its fur. A prolific painter and sculptor, an author of 34 books, a polemicist, a public speaker and lecturer. An architect who was called upon to design an entire city from scratch. A divisive urban planner who dreamed of razing central Paris to the ground to make space for concrete skyscrapers.

Le Corbusier’s work is now studied and debated by scholars and architects the world over. He was an artist who pioneered his own unique style, and whose avant-garde constructions have been enshrined as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin was never implemented. Image: FONDATION LE CORBUSIER

Born in Switzerland on October 6, 1887, Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris – he reinvented himself as Le Corbusier, a derivative of his grandfather’s surname of Lecorbésier, and took French citizenship after moving to Paris – has left an indelible mark across the globe.

The son of an artist who enamelled and painted clock and watch dials, and a music teacher, he was sent to the local arts school with a view to take on his father’s business. Learning about art history, drawing and painting, he was taken under the wing of Charles L’Éplattenier. Le Corbusier later hailed the painter and architect as his mentor. Years of apprenticeships, travel, and honing his skills alongside L’Éplattenier in Switzerland followed before Le Corbusier finally moved to Paris in 1917. Changing his name, according to the fashion of the time, and concentrating on painting, he became very much part of the Parisian artistic scene. Together with friend and Cubist painter Amédée Ozenfant, whose looks and paintings are eerily like those of Le Corbusier, he founded the Purist movement – a more rounded version of the Cubist style.

In 1920, Le Corbusier launched L’Esprit Nouveau, a polemic avant-garde review with Ozenfant and the poet Paul Dermée. Three years later, he published a selection of his writings and essays in Vers une architecture; a ground-breaking tome exploring the concept of modern design and a manifesto for a generation of architects.

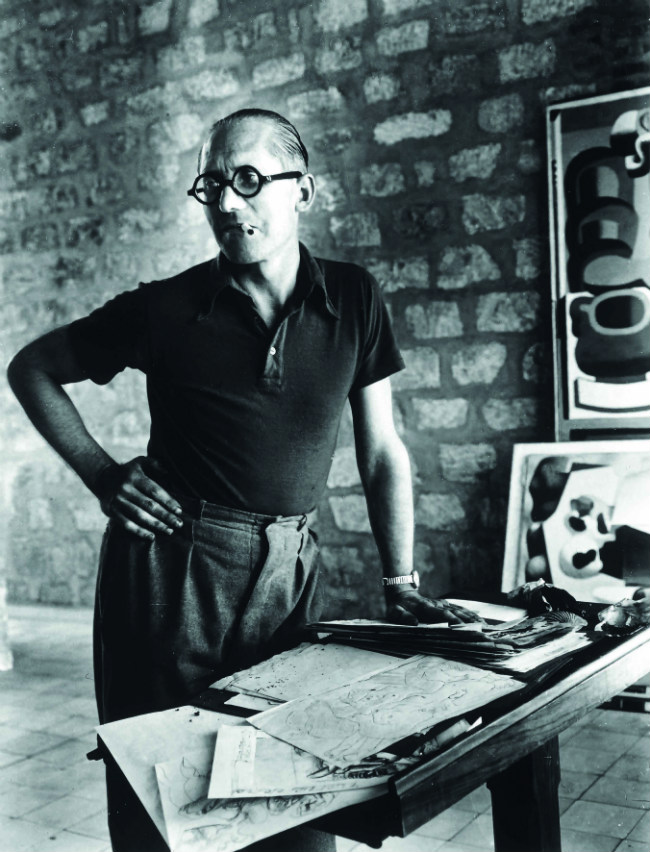

Le Corbusier. © FONDATION LE CORBUSIER

FIRST BUILDINGS

At this time, Le Corbusier designed his first important buildings in Paris: Maisons La Roche and Jeanneret, neighbouring private houses located in a cul-de-sac in the 16th arrondissement. Now home to the Fondation Le Corbusier, Maison La Roche is open to visitors, while Maison Jeanneret houses the organisation’s offices. Widely regarded as one of the first genuinely modernist houses, Maison La Roche perfectly encapsulates Le Corbusier’s ‘five points’, the essential principles of his design vision:

(1) The building, or part of it, is raised on pilotis and held up by the load-bearing columns; (2) the absence of supporting walls means the house is unrestrained in its internal use; (3) the free design of the façade sets it free from structural constraints; (4) horizontal, or ‘ribbon’, windows, mean each room is equally lit from wall to wall; (5) roof gardens bring nature into the house, offer a space for leisure and recreation, while providing essential protection for the concrete roof.

Painting by Le Corbusier inside Maison La Roche

Inside Maison La Roche, a sensually curved ramp leads to the first floor. The sparsely-furnished house is peppered with his paintings, sculptures and – ironically perhaps – a large, comfortable armchair; despite his having been quoted as saying: “Chairs are architecture, sofas are bourgeois.” Set among the typically Parisian stone buildings with their irregular roofs and gardens, the stark white and clean-lined Maison La Roche stands out as a fine example of Le Corbusier’s quest for functionality and his firm belief that a house should be “a machine for living in”. Whether or not you agree with his aesthetic, his pioneering concepts influenced generations of architects and visionaries and continue to inspire many today.

Nathalie’s Talec’s Gimme Shelter installation is based on a Le Corbusier module. © MMXI A. Nossovski & S. Dwernicki.

“I think that Le Corbusier’s principles are still relevant today, and will also be relevant years from now,” explains Aleksandra Norman, a Paris-based architect. “They are beyond trends and actually touch the core of design: functionality. His concepts lead to projects that are simple yet very efficient and attractive; which can be easily interpreted according to the times we live in. Besides, geometrical design, so typical for him and his time, can never become outdated. His legacy is very important to me, as a base for my design approach and my personal style as well. I wish I could have been a part of Modernism.”

Venturing out of Paris, I head to Poissy-sur-Seine to behold what is for me Le Corbusier’s most accomplished confection: Villa Savoye. Built in 1928, the private house is a picture-perfect example of his five design points and sits in lovely gardens, with an equally well-designed gardener’s house near the entrance. The monastic bedrooms are offset by a blue-tiled bathroom, and the serene roof terrace must once, before the trees grew to their current height, have offered a grand view of Paris.

Spiral staircase inside the Villa Savoye. Photo: © FONDATION LE CORBUSIER

UNITÉ D’HABITATION

In the late 1920s, the idea of mass housing and urbanisation across the world captivated Le Corbusier, who stated: “The materials of city planning are: sky, space, trees, steel and cement; in that order and that hierarchy.” Although probably conceived with the best of intentions, many of his early schemes were rather ambitious. We can only be grateful that his ‘Plan Voisin’, which involved tearing down central Paris’s 3rd and 4th arrondissements and erecting gigantic skyscrapers, never came to fruition. He kept designing self-contained villages, approaching the mayors of many large cities around the globe, and often getting rebuffed… But he did gradually end up building several of his grand projects in such countries as India, Brazil and Argentina.

Inside street, Unité d’Habitation, Firminy. © FONDATION LE CORBUSIER

In France, his first Unité d’habitation, the Cité radieuse in Marseille, is still one of his most impressive master-works. Dubbed “Maison du Fada” (house of the madman) by nonplussed residents in the 1950s, it is fair to say the concrete monolith split opinion and still does today. Though, since it was awarded UNESCO World Heritage Site status, many have come round to its brutalist edge. Far from a soulless residential block, the cliff-like stack of 337 flats is a self-contained ‘vertical village’ with shops, offices, a hotel, restaurant, doctor’s surgery and even a nursery school. The windows ribbon across the length of the building, bathing the duplexes both in morning and afternoon light. The roof is a playground for the school and a recreational space, complete with gardens and running track for the residents. Every third floor of the 15-odd-storey building is an internal street onto which the individual apartments open. Although not aesthetically pleasing at first glance, the high-rise was a dizzying feat of architecture at the time. Carefully thought through, it followed Le Corbusier’s novel Modulor system – a unified scale of measurement based on the human body – and was designed for maximum comfort. A faithfully re-created apartment from the Cité radieuse is on display at the Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine in Paris.

Maison de la Culture, Fiminy. Photo: Olivier Martin Gambier

Other Unités d’habitation in France can be found in Rezé, outside Nantes, and in Firminy. All pay tribute to Le Corbusier’s initially controversial ideals, in that the communities are still blossoming, schools are still functioning, and residents are embracing the idea of classless community living.

Staying overnight in an apartment in the Unité, I meet Yvan, curator for the Fondation Le Corbusier in Firminy, who has lived in the building for more than 30 years. He firmly believes Le Corbusier’s idea that “the highest level of productive planning coincides with the maximum productivity of spirit” is still true today. “I am in touch with residents of the units in Berlin, in Rezé and in Marseille. The communities are thriving, and the concept works. Even now.” And spending time in the well-lit apartment, I have ample time to appreciate the dimensions, even though I am not the perfect 1.83m Modulor man (rather a 1.59m-tall woman). Watching children play, university students working in the former school, and neighbours all greeting each other, it’s clear Le Corbusier hit the bull’s eye.

Église Saint-Pierre, Firminy. © FONDATION LE CORBUSIER

FIRMINY AND BEYOND

A short bus ride out of Saint-Étienne, the UNESCO City of Design of Firminy is home to the largest collection of Le Corbusier buildings in Europe. The Site Le Corbusier holds a cultural centre, stadium, church and swimming pool, all designed and planned by the architect; though many were completed after his untimely death in 1965 – when he drowned near his home in the south of France.

Le Corbusier’s La chapelle Notre-Dame-du-Haut, Ronchamp. Photo: Paul Kozlowski

And the rest of the Hexagon is dotted with Le Corbusier’s concrete masterpieces; not least Ronchamp, which boasts one of his more elegant, and unusual, projects: the Chapelle Notre-Dame du Haut. Among his portfolio are also several student residences not unlike his famous Unités d’habitation.

But one of his most unique, if sadly neglected, ‘sites’ is undoubtedly his barge conversion or “floating shelter” along the Quai d’Austerlitz. Yes, it is made from concrete. And yes, it does float.

From France Today magazine

The péniche at Quai d’Austerlitz. Photo: © FONDATION LE CORBUSIER

Maison Planeix, Boulevard Masséna, Paris. Photo: © FONDATION LE CORBUSIER

Modulor man outside the Unité d’Habitation, Firminy. © FONDATION LE CORBUSIER

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY