The Santons of Provence: A History

In Provence the holiday season belongs to the colorful world of santons—santous or santoùos in Provençal, “little saints” to the rest of us. A wrinkle, the shining dot of an eye, a graceful pose, the tilting of a hat, a lace bonnet, a weary back stooped by toil and age, a smile of contentment, an ample fold in a garment—since these clay figurines are often no bigger than Hans Christian Andersen’s Thumbelina, you will not be surprised that 85% of the cost goes to labor, a far cry from the modern mass-production Christmas industry. The making of a santon is a labor of love.

Figurines have been part of the human experience since time immemorial, often as effigies of the gods. The santons of Provence stem from the first living Nativity scene, said to have been created in 1223 by St. Francis, in Greccio, near Assisi. When these evolved into Nativity crèches (manger scenes), they were made of painted and gilded wood and set up inside churches. In time they became luxury artifacts, adorned with Venetian glass and fine porcelain, acquired by wealthy families as status symbols. When wax came into use in the 17th and 18th centuries, likenesses of the high and mighty rivaled those of the Holy Family, flattering the vanity of their owners, not least Louis XIV who owned seven scale models of himself. The mechanized crèches that appeared in the late 18th century were altogether removed from the church and displayed in small theaters. The kicking feet of the infant Jesus delighted the crowds but were hardly conducive to spiritual meditation.

The crèche also had a political stake: whereas the pious scenes had served to combat the Protestant Reformation in the 17th century, they were banned during the French Revolution. When the churches were closed down by the anticlerical revolutionary authorities in 1794, people started making them in secret at home, using cloth, papier mâché, even bread—whatever came in handy. It was a daring thing to do in the shadow of the guillotine. Some people even showed them to visitors for a tiny admission fee.

In Marseille, Jean-Louis Lagnel started a different kind of revolution in 1797, when he molded the small figures out of clay, making them affordable for ordinary people. The word santon, however, was not recorded until 1826, four years after Lagnel’s death. Besides, Lagnel’s santons were not fired, as santons are today. It was not until well into the 20th century that Thérèse Neveu from Aubagne, a small town north of Marseille, had the idea of doing so, in order to make the figurines more resistant. Regarded as the first modern santonnière, Neveu won praise from writer and poet Frédéric Mistral, the recipient of the 1904 Nobel Prize for literature, who developed and promoted the Provençal language. Neveu’s brother, Louis Sicard, gained equal fame as a ceramist and as the creator of the ceramic cigale (cicada), a Provençal symbol that is still being made today at the Maison Sicard in Aubagne, side by side with present-day santons.

The santon was a child of the French Revolution, paradoxically invented by a counterrevolutionary. It was egalitarian because it represented in miniature the entire spectrum of post-Revolution Provence—commoners all, little people most, aristocrats none, except for the royal Magi. It was counterrevolutionary because it incorporated the Nativity scene into its secular world. Ultimately free-spirited, for a time the crèche antagonized both the Church and the Republic. The Church tolerated it only as trivial entertainment for children; the homogenizing French Republic frowned upon it as a subversive expression of regional identity. But the people loved these little figures, who seem to have made their first official public appearance in 1803, within the framework of the Foire aux Santons, held in Marseille by three vendors. The sale of 180,000 santons, recorded in 1886, illustrates their persistently growing popularity despite the hostility from higher quarters. Today hundreds of santonniers work all over southern France, even far from Provence in the remote heartland of the Aveyron and the Lozère.

It is Thérèse Neveu’s hometown, Aubagne, that takes prominence. The city’s clay industry dates from Roman times, and provided employment to a quarter of the population at its peak. Heavily industrialized in the 19th century, Aubagne was dubbed “un Glasgow Provençal”. No fear—the chimney stacks have all been leveled, the clay is no longer locally extracted and present-day Aubagne goes by the more inviting designation of “Capitale du Santon”.

Many santonniers work in family businesses, ranging from Daniel Scaturro, winner of the prestigious Meilleur Ouvrier de France distinction, who does nearly everything by himself while his wife makes the miniature clothes, to the Escoffiers, mother and children, who have 40 employees. Florence Amy’s late father, Raymond, was a multi-talented sculptor, painter and archaeologist who caught the santon bug; her mother Sylvette came from the theater world and had been a dancer. “When you come from this creative and artistic background,” said Florence, “you either love it or hate it. In my case, it’s been love.” Didier, Véronique and Daniel Coulomb learned the trade from their late aunt, Maryse Di Landro; today it is Véronique’s husband Pascal who makes the santons, while Véronique designs the costumes.

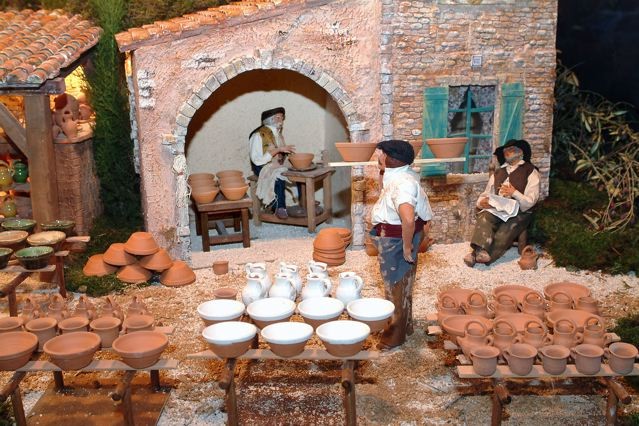

The Provençal crèche is the mirror in miniature of a 19th-century Provençal village. There is the miller carrying his sack of flour on a donkey, the farmer’s wife with her basket of fresh eggs, the schoolmistress and children, the farandole dancers, Monsieur le Maire and Monsieur le Curé. Other characters are drawn from Antoine Maurel’s Pastorale, a Provençal re-writing of the Nativity story in which the sacred and the profane are intertwined. Roustido, who arrives late because he is hard of hearing; Pimpara, the traveling knife grinder who never fails to report a piece of gossip; the fishwife; the simple-minded Pistachié; the blind man who recovers his sight on the night of the Nativity; the angel Bouffarel with his puffed up cheeks as he blows the trumpet to announce the arrival of lou pitchoun—the infant.

By good fortune, Aubagne is also the birthplace of author Marcel Pagnol (César, Marius, Fanny, Manon des Sources, La Gloire de Mon Père, Le Château de Ma Mère) allowing the santonniers to cash in on his characters and on those who embodied them on the screen, France’s beloved comic actors Fernandel and Raimu in the lead. All the santonniers of Aubagne contributed to Le Petit Monde de Pagnol, a charming museum set up in the former bandstand of Aubagne. It houses a spectacular miniature Pagnol scene set up against a plaster model of the Garlaban mountain above Aubagne, a hiker’s paradise where several of Pagnol’s movies were filmed. Come December 3, the Pagnol characters are removed and put away in a cupboard. On the following day, the feast of Sainte Barbe, which marks the beginning of the Christmas celebrations, they are replaced by the traditional figures of the Nativity story. They will be swapped back on February 2, the feast of la Chandeleur (Candlemas), when the Christmas celebration ends.

The world of santons is a fascinating blend of fantasy and realism. A santonnier will spend long hours in the hills in search of twigs and plants for his accessories. A bit of thyme can work for a Lilliputian olive tree, to which he will glue black beads the size of a pinhead. Coming from the Sèvres porcelain manufactory, decorative artist Marianne, working at the santon-maker Escoffier, derives great pleasure from applying to the clay the bright-colored motifs of Provençal fabrics. This is when the santon is santonnifié—in other words, comes to life. Time and again I was shown with pride the impeccable workmanship of a garment, the perfect finish of a buttonhole or of the stitching of an underskirt that no one will see—just as is required in life-sized French haute couture. Careful attention is paid to old customs: the green, rather than white, wedding dress of a bride; the housewife who wears her house keys attached to her clothing, as women did from their wedding day on. Finally, when mounting the crèche, the santons are positioned according to size to create a sense of perspective.

Anachronisms are given free rein in the santon’s world of popular fantasy. Twentieth-century characters occasionally land in the 19th century and a village priest in a black cassock may be seen by the side of the infant Jesus. The Provençal crèche is open ended, and some santonniers refuse to freeze it in the past. Santonnier Daniel Scaturro has made several clay likenesses of recent French presidents. Apparently, President Sarkozy is pleased with his effigy and keeps one on his desk.

Santonnier Daniel Coulomb trod on more sensitive ground when he imbued the sacred with a touch of realism. Although he cautiously consulted with a priest before making a pregnant Virgin Mary, his initiative at once made the headlines of the newspaper La Provence and aroused excitement among all the major television channels. Whether conceived by the Holy Spirit or not, pointed out Daniel’s brother Didier, it has never been denied that Mary gave birth to Jesus. Consequently it is no sacrilege to represent her with child. On the other hand, in the name of realism, that figurine must be replaced on December 24, at midnight, when the infant is laid in the crib. Needless to say, Daniel Coulomb’s Virgin was an instant commercial success, with sales soaring above 1,000 within the first two days.

Visitors are welcomed into santonniers’ workshops and collections throughout the year. Maryse Di Landro also offers guided tours of her workshop, walking guests through the different phases of production, the molding, drying, firing and decoration, enjoyable even for those who don’t understand much French. The Musée du Santon et des Traditions de Provence in Fontaine de Vaucluse boasts the largest collection, over 2,500 santons, and the world’s tiniest crèche, made from a nutshell.

The most exciting time to visit, of course, is in December. The village of Grignan boasts a giant crèche with over 1,000 santons and enchanting sound-and-light effects. There are well-known Foires aux Santons in Marseille, Aix-en-Provence, Arles and Aubagne, which also organizes a Biennale aux Santons every even year. Its highlight is the pastorale procession, complete with real sheep and Provençal music, which departs on Saturday evening from Saint-Sauveur Church on top of the hill and winds its way down the streets of the old town to the Cours Foche, where real-life “santons”, in their traditional costumes, dance the farandole of the Provençal crèche.

SANTONS NOTEBOOK

Office de Tourisme du Pays d’Aubagne 8 cours Barthélémy, Aubagne, 04.42.03.49.98.

Escoffier 144 rue du Vallat, Zone Industrielle des Paluds, Aubagne, 04.42.70.14.32.

Maryse Di Landro 582 ave des Paluds, Z. I. des Paluds, Aubagne, 04.42.70.95.65.

Daniel Scaturro 20A ave de Verdun, Aubagne, 04.42.84.33.29.

Sylvette Amy/Maison Sicard, Les Deux Provençales, 2 blvd Emile Combes, Aubagne, 04.42.01.39.62.

Le Petit Monde de Marcel Pagnol Esplanade Charles de Gaulle, Aubagne.

Musée du Santon et Traditions de Provence Place de la Colonne, Fontaine de Vaucluse, 04.90.20.20.83.

From the France Today archives

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY