Winston Churchill’s Brush with the Riviera

Renowned as the man who led Britain to victory in the Second World War, Winston Churchill found solace and joy in his painting expeditions to the French Riviera, as Paul Rafferty discovers

August 1948, Aix-en-Provence, late afternoon, the baking heat by now just about bearable. A convoy of artist, driver, valet, bodyguards and a Life magazine photographer rumbled down the three mile, paved road towards Le Tholonet to the east of Aix-en-Provence. They stopped at a hairpin bend in the country road; for a moment the cicadas stopped with them. After setting up the easel, parasol, whisky, soda, cigars, paints and brushes, table and chair and donning a Stetson hat, Winston Churchill committed the iconic Montagne Sainte-Victoire to canvas. Later, over dinner at the Hôtel Roi René at Aix with family and friends, Churchill spent several minutes deep in thought. Suddenly, he broke into the conversation and said rather gravely: “I have had a wonderful life, full of many achievements. Every ambition I’ve ever had has been fulfilled, save one.”

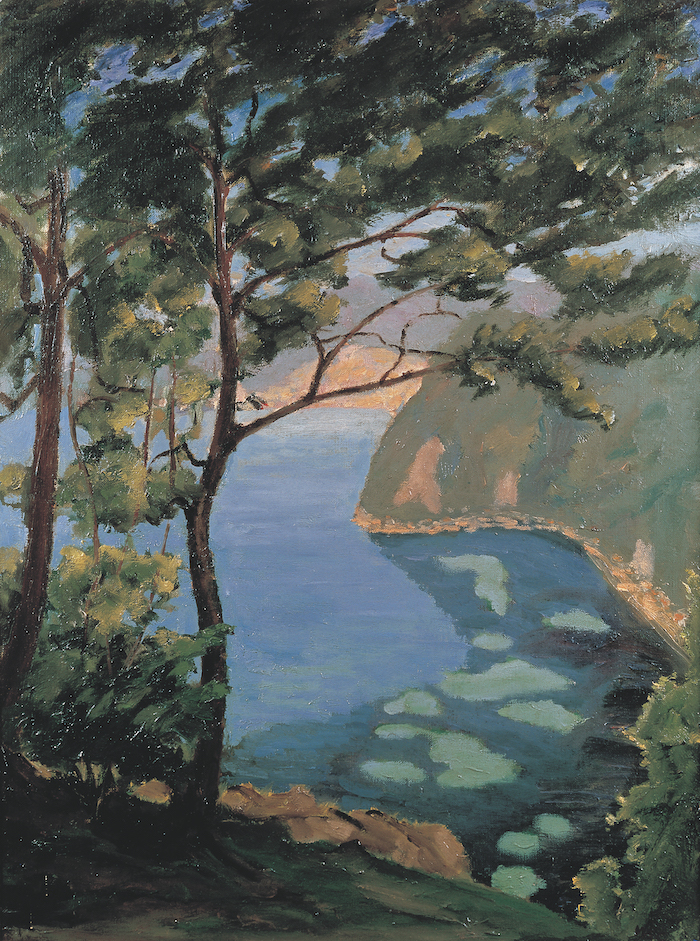

- Bay of Eze. Photo credit © Paul Rafferty

- Bay of Eze painting, C490. Photo credit © Churchill Heritage

“Oh, dear me,” said Lady Churchill, “what is that?” “I am not a great painter,” he replied. As he wrote in Painting as a Pastime: “We cannot aspire to masterpieces. We may content ourselves with a joyride in a paintbox. And for this, audacity is the only ticket.”

So how did this audacity play out in practice? Churchill worked directly on to a white canvas, with no ground colour. This is how the Impressionists worked, letting the lead white ground impart the most light through the oil paint. An aide squeezed out at least 15 colours in order on to his palette: along with his bright colours, there would be earth tints, ochres and neutral tints, but no black.

Churchill loved all the blues, Cobalt, French Ultramarine, Prussian and what he called the “British true blue – that cerulean, a heavenly colour we all admire so much”. His tendency towards rather acid greens is evident in many canvases – though, in his defence, they often resemble their aide-mémoire photographs very well. He routinely rounded out with Rose Madder, Vermilion Reds and Cadmium Yellows. Flake White from Blockx, as recommended by the respected British artist Walter Sickert, would often be found centre stage on the palette.

Painting at the plage de la Garoup Cap d’Antibes. Photo credit © Paul Rafferty

Churchill then mapped out the composition on the canvas, often with thin lines in blue paint, after which he boldly laid in his colours with a large brush, likely thinning his paints with a half-and-half mixture of turpentine and linseed oil, as per Sickert’s instructions. He is often to be seen with one small glass cup, containing this thinning mixture, on his palette. His brushmarks were influenced by the Impressionists, direct, colourful and loose. He was trying to capture a moment in time, with the brilliant effects of strong lights and dark shadows exciting him most. Thus his paintings had to be executed quickly: after two hours, the scene would change dramatically, especially at the time of day Churchill favoured.

Concentration and focus were needed for these large canvases. If a painting was going badly he would grumble about it and, muttering ‘That’s no good,’ scrape the offending part off with his palette knife, leaving a ghost impression, making a better attempt possible with subsequent layers. In the final stages of a painting, he used a smaller brush to show details such as leaves and flowers, resting on his mahl stick as he brought the painting to life. As the light faded, he took the unfinished canvas back to base camp, and later, at home in his Chartwell studio, he adjusted sections, or re-worked the whole. These paintings could become heavily layered with thick paint, losing some of the transparency and freshness.

- C417. Photo credit © Churchill Heritage

- Port Crouton. Photo credit © Paul Rafferty

Churchill came to painting relatively late in life, not starting until 1915 when he was 40 years old; before then he had only displayed as much interest in the arts as official duties required. The period following the First World War was a difficult time for him, and Gallipoli was too recent a memory. He was angry, frustrated, depressed, restless. Then, as he later recalled in Painting as a Pastime, “the Muse of Painting came to my rescue – out of charity and out of chivalry, because after all she had had nothing to do with me – and said, ‘Are these toys any good to you? They amuse some people.’”

Homage to the Heroes

Churchill’s adventures with paint were not entirely self-taught, his London neighbours, John and Hazel Lavery, being the first to influence him professionally. It was Hazel who banished any fear of a white canvas at Hoe Farm, as did John later, both on location at Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat and in his London studio. All his artist friends gave encouragement, some with gentle words of advice such as his dear friend Paul Maze.

- C207. Photo credit © Churchill Heritage

- Tourettes. Photo credit © Paul Rafferty

Walter Sickert wrote down explicit instructions on his methods which Churchill devoured, though he could not adapt to his sombre colours, preferring a brightly coloured palette. He also taught him to use a magic lantern to project a slide or negative on to the canvas, quite a revelation to Churchill. When his bodyguard Ronald Golding saw him using it in the studio, he said: “With respect, sir, it looks a bit like cheating.” But Churchill was having none of it. From over his painting glasses, he said solemnly: “If the finished product looks like a work of art, then it is a work of art, no matter how it has been achieved.” He made many copies of works by artists he admired, such as Sargent, Monet, Lavery and Daubigny.

In particular he looked up to the great Paul Cézanne, who when describing the ever-changing light on the seemingly unchanging Montagne Sainte-Victoire said: “Everything vanishes, falls apart, doesn’t it? Nature is always the same, yet nothing in her that appears to us lasts. Our art must render the thrill of her permanence, and along with her elements, the appearance of all her changes. It must give us a taste of her Eternity” – words Churchill would have surely read as he would have studied Cézanne’s art.

Painting for Churchill was more than creating art; it was also more than a passing pleasure, a pastime. It was a therapy for him, a passion which enlivened him and never failed to hold his attention. Hours with a brush and palette in his hands were for him, according to his valet Norman McGowan, akin to being in paradise. Maybe not everyone’s idea of paradise as McGowan also observed: “He was painting. As usual he was grumbling all the time to himself. ‘That’s no good,’ he muttered and scraped off the oil paint again. It was an unwritten rule that no one ever looked over his shoulder. He could not stand it and made no bones about his feelings if anyone ventured too near.”

C244. Photo credit © Churchill Heritage

This was one area in which Churchill the artist was uncharacteristically modest, always underestimating his own talents but quietly proud of his efforts all the same. This is borne out by letters home to his wife, Clementine. He loved to send the canvases home before him and hoped she would await his return before opening them, so they could unwrap them together for the big reveal.

Painting on the French Riviera documents Churchill’s love affair with the Côte d’Azur. It began in the early 1920s on a painting expedition with Sir John Lavery. Two years later Churchill rented the Villa Rêve d’Or in Cannes for six months over winter and fell under the French Riviera’s spell. For the next 30 years, staying with friends as an honoured guest in the finest châteaux and villas along the coast, he revelled in what he called the ‘paintatious’ subjects all around him.

Chapel St Cassien, Cannes. Photo credit © Rafferty

A Full Entourage

As well as visiting his influential press baron friends and other dignitaries and celebrities, Churchill stayed with the Hollywood actress and Broadway impresario Maxine Elliott at the fabulous Château de l’Horizon in the 1930s. From the steps of the villa directly on the Mediterranean, with the l’Esterel mountains to the west and Cap d’Antibes to the east, Churchill ventured out to paint in favourite locations: Saint-Paul de Vence, Plage de la Garoupe, The Red Rocks at Cap Roux and Saint-Raphaël. All were within striking distance.

He always painted with an entourage, consisting at least of a driver, bodyguard, valet and secretary, and often on arrival, a gendarme or two. In the many previously unpublished photographs in this book, we see him painting on location, with the entourage on standby and Churchill himself surrounded by his ‘draught excluder’ screen, sun parasols and painting paraphernalia and various forms of refreshment; an artist with his own caravanserai.

The fact that after the Second World War he was the most recognisable figure in Europe only added to the eccentricity, much appreciated by the small crowds who gathered in wonder at the singular sight before them. Unimpressed, or simply not recognising him, one old Frenchman wandering past advised him that “with a few more lessons you will be quite good”.

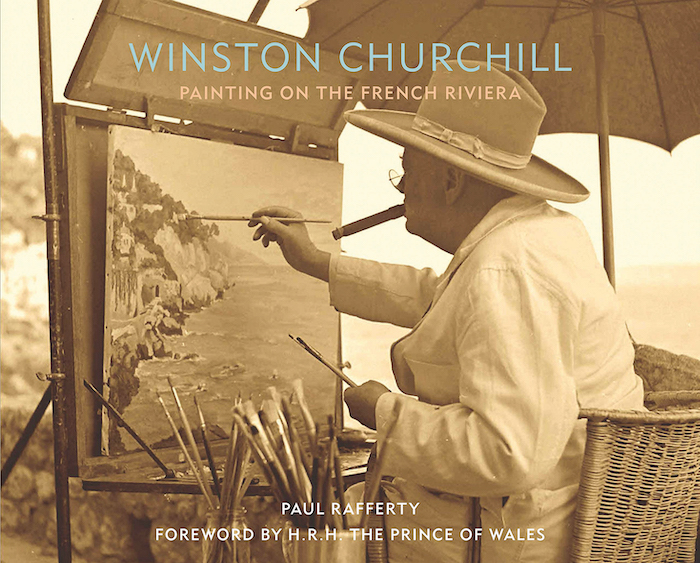

Winston Churchill’s “Painting on the French Riviera”, book cover.

In Plain Sight

In this book I want to celebrate not just Churchill’s paintings of the South of France, but also the joy in finding his locations here: When a location is found, it suddenly becomes obvious that this is it, as if it had been hiding in plain sight all the time. I cannot share enough the thrill of discovering an unknown location; still more so when visiting it for the first time, confirming my detective work and then soaking up the space, reluctant to leave, quietly enjoying the hidden knowledge that no one else knows that this is the spot, while at the same time wanting to share this find with anyone who will listen.

Excerpted with permission from ‘Winston Churchill: Painting on the French Riviera’, by author Paul Rafferty, published by Unicorn at £35.

From France Today magazine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY