21st Century Chartres: The Famous Gothic Cathedral is Newly Restored

One of the world’s most famous cathedrals has emerged resplendent after a recent restoration, though some say it has lost something

There is nothing like it in all of France. Rising like an apparition from the wheat fields, the majesty of Chartres Cathedral is palpable to visitors approaching by car, train, or on foot – as many pilgrims still do – long before they step through its doors. But for those who know Chartres, stepping through its doors is now a monumental surprise. Gone is the deep, atmospheric gloom out of which glimmer the world’s most glorious stained-glass windows, replaced by a soaring expanse of luminous white.

The cathedral’s vaulted ceilings.

In September, as the last of the scaffolding came down on a sweeping, €20 million restoration slated for completion sometime in 2020, parishioners and visitors witnessed an unprecedented transformation. For some, the emergence of these 13th-century stones from elegiac dusk to brilliant dawn is a revelation, for others an irreversible tragedy.

The cathedral in Spring. Photo: Office de Tourisme de Chartres Métropole

A FIGHT OVER THE GOTHIC SOUL

A UNESCO World Heritage Site unanimously considered a pinnacle of Gothic architecture, unlike so many of France’s great churches Chartres has weathered history’s fires, wars, and revolutions relatively unscathed. But it has not escaped time; nor, some will say, human folly.

Though sections – notably the 12th-century west front, its royal doors and two contrasting towers – predate the devastating fire of 1194 that destroyed the cathedral along with much of the city, most of the church was built in an astonishingly short period, from about 1195 to 1220, which accounts for its unusually homogeneous style. What today’s visitors see, excluding an incongruous 18th-century makeover of the choir, is an exceedingly graceful assemblage of upwardly thrusting pillars and airy vaulting interspersed with the arched raised galleries that culminate in Chartres’s peerless windows.

From afar, the cathedral doesn’t seem to have changed. Photo: G Osorio

But 800 years of candle soot, incense, fires, and a misguided oil-burning furnace installed in the 1950s had sullied the interior and windows with a heavy coating of black grime. The ensuing twilight that obscured much of the cathedral’s Gothic detailing – originally intended as the recreation of heaven on earth – proved the ideal backdrop for Chartres’s exquisite windows, which shone through the dusk like glimmering gems. The overarching effect was a space both intimate and exalted, where generations of the faithful and non-believers alike found contemplation, uplift and grace. But the building’s walls, vaulting and pillars suffered.

“There was an acute conservation issue for these areas; we had to place nets to catch the falling plaster from the vaults, and the nets obscured visitors’ view,” says Irène Jourd’heuil, Curator of Historical Monuments Department of Cultural Affairs for Central France. “Something had to be done.”

The dramatic restoration is clearly visible inside. Photo: Jennifer Ladonne

Studies undertaken before the restoration showed that simply by rubbing off layers of accumulated dust, which included the residue of two other coatings, from the 15th and 19th centuries, an original 13th-century layer applied over the exposed stone was revealed in an exceptionally well-preserved state. This discovery opened a new chapter in conservators’ thinking about how to approach the project. As Jourd’heuil explains: “It was long believed that Middle-Ages stones were not painted on and left raw, and many original décors were simply scraped off. Now we know the stone was coloured.”

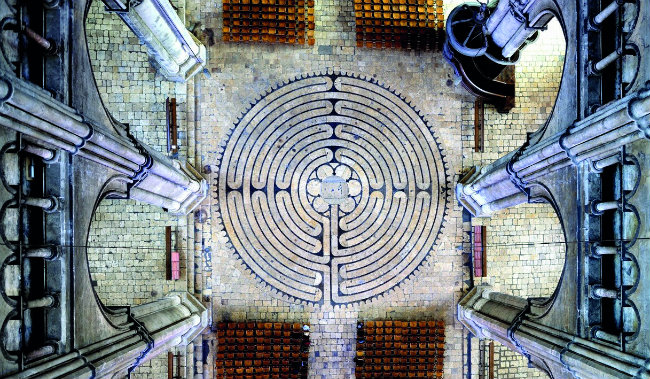

Angel’s eye view of the labyrinth. Photo: Alain Kilar

Excitement over the surprisingly intact state of the original colouring opened new questions and new curiosities about what else might lie beneath. The step-by-step restoration, painstakingly performed with mini-vacuums, brushes, and scalpels, found a remarkable 80 per cent of the cathedral’s original coating – of a beautiful pale ochre colour with lighter lines to indicate the masonry – to be salvageable. The remaining 20 per cent, including the pillars, was repaired and re-covered with a light wash created to match the composition of the original as closely as possible. Now, with all the walls and ceilings completed, except for the transept’s north and south wings, which remain in their original pre-restoration state – each with its spectacular rose window – the cathedral’s interior looks almost new. And therein lies the rub.

The cathedral’s south facade. Photo: JS Mutschler

MEDIEVAL GLORY OR SCANDALOUS DESECRATION?

The restoration team was unprepared for the furious backlash spearheaded by outraged art historians, conservators and scholars who contend that the restoration wipes away not only the dirt but the cathedral’s ineffable majesty and profound spirit of place. Some have vehemently denounced the result, at best calling it “fake”, at worst, as stated by the American architectural critic Martin Filler in the New York Review of Books blog, “the scandalous desecration of a holy place”.

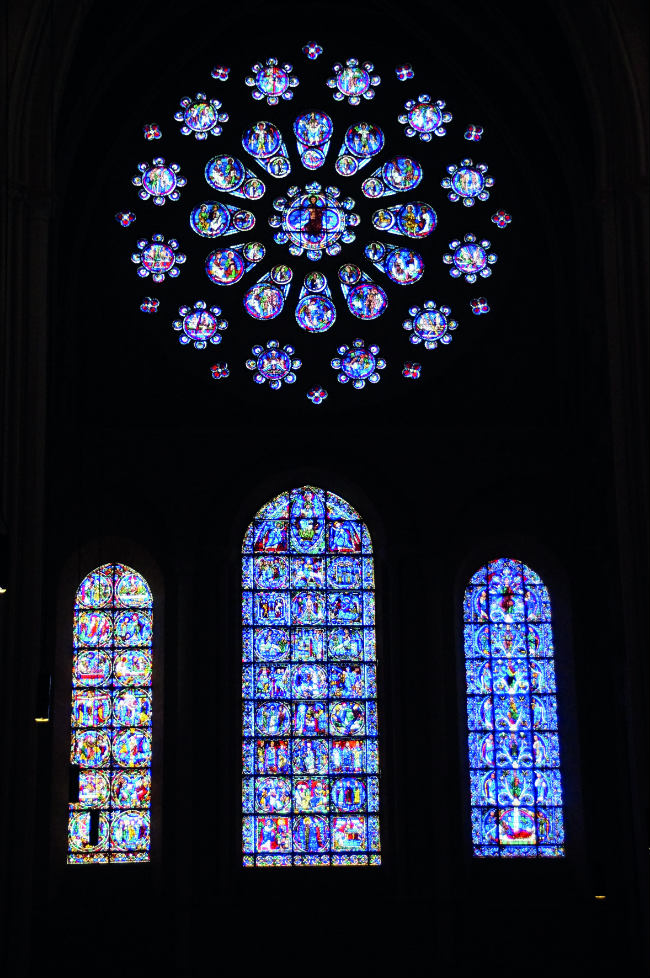

Part of the world’s most important collection of medieval stained glass. Photo: C Mouton

What’s more, say the critics, ambient light reflecting off newly radiant walls and ceilings, as well as the controversial addition of electric lighting, vastly diminishes the experience of the windows, Chartres’s crowning glory, resplendent after a thorough cleaning – the one aspect of the renovation that has been unanimously lauded.

It does not stretch the imagination to view Chartres as having been wiped clean, airbrushed into a fantasy of a glorious Medieval past. And some visitors have expressed anger over the loss of the Chartres they knew. “But most are pleased with the results,” says Anne Marie Woods, a guide at the cathedral since the start of the renovations.

The famous stained glass windows in the Chartres Cathedral. Photo: E Vandenbroucque

A CASE OF MISTAKEN IDENTITY

Perhaps the most eloquent symbol of the controversy is the famous Black Madonna, a focal point for pilgrims – along with Chartres’s important relic, the Veil of Mary, given to the church by Charles the Bald, the son of Charlemagne, in 876. Blackened from years of soot, along with what turned out to be a more recent coat of black paint, the Madonna and the Christ child on her lap emerged in 2013 from the restoration lab pale and apple-cheeked. “We studied the statue’s polychromy and found it dates from the 16th century. It was concluded that the paint was recent, dating from the 19th century. She was not conceived as a Black Virgin.”

Statue at the Chartres Cathedral. Photo: C Mouton

The Black Madonna, explains Jourd’heuil, was probably conflated with the Virgin of the Crypt, a statue of the Virgin venerated in the cathedral’s crypt since the Middle Ages and burned during the Revolution. The Virgin of the Crypt itself may or may not have been a copy of a Celtic statue already venerated in Druidic times in a grotto spring over which the cathedral was built. Inscribed Virgini pariturae, “the virgin who will give birth,” its significance for early Christians resided in its seemingly miraculous presaging of the Annunciation.

Though this story is now cited as a myth, Chartres was certainly the centre of a ‘cult of Mary’ and was, according to the religious scholar Titus Burckhardt, “the principal sanctuary of the Mother of God in France”. Jill KH Geoffrion testifies to the Virgin’s pre-eminence in the “many overt and subtle Marian symbols both inside and on the outside of the cathedral” exquisitely detailed in her newly published Visions of Mary: Art, Devotion and Beauty at Chartres Cathedral.

La Vierge du Pilier

Whether it is a conscious effort to erase any trace of the mythical Black Virgin, an indelicate correction of an ancient yet misguided custom, or whether the Black Madonna is simply a casualty of the restoration’s earnest attempts to remain true to the spirit of the medieval church, depends on whom you ask.

But there is no question that important discoveries were made to advance the existing understanding of the church in the Middle Ages, including some surprising illustrations of rose windows painted high up in the north and south narthex, the brightness of the pillars of the arched triforium just below the stained-glass windows, and two curious black shields, inscribed with the words ‘République Française’, left over from the church’s eight years of post-Revolution desacralisation, uncovered like a palimpsest on opposing pillars facing the front altar.

The interior of the Chartres Cathedral

For now, while the cathedral awaits its final phase, the north and south wings of the transept retain the ancient black, allowing visitors to judge for themselves the effect of the transformations. But the cathedral’s longest living ‘inhabitant’, Malcolm Miller, a Chartres scholar, lecturer and author who has given daily tours of the church for the last 60 years, is unequivocal:

“I think it’s marvellous.”

From France Today magazine

Statuary at the North Portal. Photo: Office de Tourisme de Chartres – Chartres Convention & Visitors Bureau_cut

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in French cathedrals, UNESCO sites

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY