The Rooster that Woke the World: The Pathé Brothers in Close-up

From humble beginnings, four brothers created a world-famous film company that captured the excitement and flair of the new medium. Hazel Smith discovers the story of Pathé

Over a century ago, four brothers born to the owners of a Vincennes charcuterie set up a film company under the family name; a name that is still familiar to contemporary cinema audiences – Pathé. The Société Pathé Frères, founded in Paris on September 28, 1896 would become the first of its kind – the largest film equipment and production company in the world.

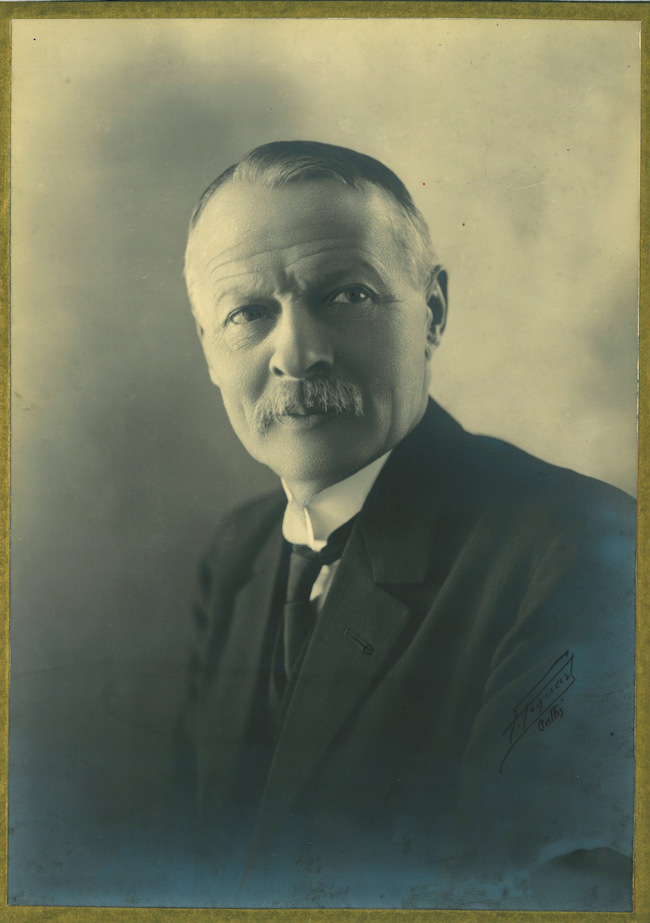

However, it was not ‘all for one and one for all’. The company’s story revolves around Charles – the public face of the Pathé brothers. His ambition and ingenuity would forever change the human experience. Instrumental in building the family business, Charles, born 1863, won the financial blessing of his brothers to travel to Argentina to try his hand at selling industrial washing machines. A bout of yellow fever sent him back to France in 1891 with empty pockets and an armload of sickly parrots he intended to resell. He had settled back in Vincennes, operating his family’s bistro, when a falling-out with his parents set Charles out on his own: 30 years old, newly married and broke.

Down on his luck, he accepted a paltry office job. His destiny changed one Sunday in summer 1894, when he visited the local fairground. Here he discovered the Edison Phonograph – a new American invention for the mechanical recording and reproduction of sound. Quickly recognising its potential, Charles scraped together enough money to buy a copy of one. After giving up his job, he began travelling the fairground circuit, charging audiences for the privilege of listening to Thomas Edison’s invention.

The innovative Charles Pathé was the driving force behind the brothers’ film enterprise. Photo: Pathé Foundation

THE BIGGER PICTURE…

He was so successful that in 1895 Charles began importing phonographs, selling them from his shop at 72 cours de Vincennes, where he had also established a recording studio. The following year, Charles added another Edison invention – the kinetoscope, a device for viewing moving pictures – and his expanded firm was soon selling Edison’s authorised motion-picture projectors.

Pathé Frères was founded in 1896 when, at his dying mother’s behest, brothers Émile, Théophile and Jacques (each with a small investment in hand) joined Charles Pathé’s growing business. Théo and Jacques eventually bowed out, but Émile remained – operating the phonograph arm of the company, while Charles took Pathé Frères even deeper down the motion picture route. Inventor Henri Joly briefly joined the Pathé adventure, developing a photozootrope (like the kinetoscope but larger) for Charles. This nickelodeon-like projector was one of the first true motion-picture devices. Charles was well on his way to developing his own film-equipment empire.

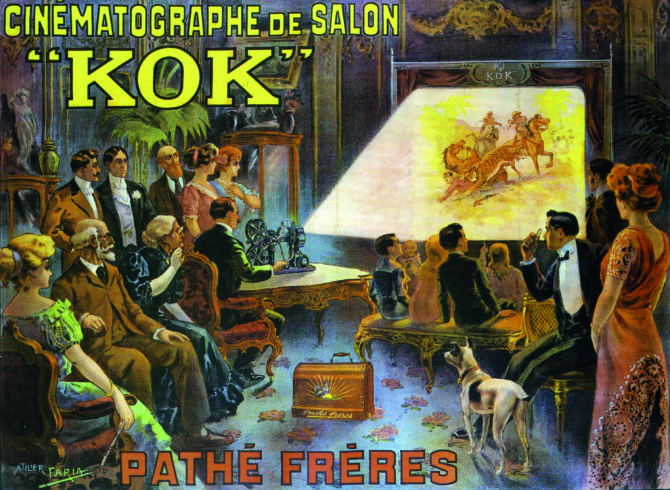

The cinématographe allowed fair-goers to watch moving pictures. Image: Pathé Foundation

In the French countryside, where electricity was a luxury, fairground cinemas were the ideal place to promote motion pictures. By 1902, nearly every fair advertised a cinema whose programme thrilled audiences with a combination of magic-lantern shows and live acts, but the short films shown by Pathé outstripped all else in popularity. In Paris, Pathé Frères’ head office was located at 98 rue de Richelieu, with a listening salon set up by Émile at 26 boulevard des Italiens.

After its first dramatic explosion, cinema developed slowly – was it just a flash in the pan? Then, a decade after its first appearance, the cinema industry grew exponentially. The success of the aptly-named Lumière brothers, rightfully credited as being the first filmmakers, encouraged Charles Pathé to make films himself. Instead of selling his films, Charles saw the potential of renting them and by the summer of 1905, Pathé had become the leading supplier of moving pictures for the American market. As Charles himself claimed: “I may not have invented the cinema, but I did industrialise it.”

Pathé’s former film studios in Paris are now home to La Fémis, the French film school. Photo: Pathé Foundation

A striptease, albeit a very modest one, was one of the first motion pictures produced by the Pathé Frères. In the 1896 Le Coucher de la Mariée, a coy Belle-Époque bride peels off her wedding clothes one layer at a time. While Le Barbier Fin de Siècle is no Sweeney Todd; instead, he demonstrates the possibilities of the new media. The barber detaches the head of his squirming client and after a close shave reunites it with the customer’s shoulders.

A still from “Le Coucher de la Mariée”

THAT’S ENTERTAINMENT

Fortune smiled on the moving-picture industry in the summer of 1906 when France’s National Assembly passed legislation mandating a weekly day off for all French workers. Charles took advantage of the need for new leisure entertainment by building permanent movie theatres in his name. His first silver screen was the 300-seat Omnia Pathé, which opened in Paris in late 1906, across from the Musée Grévin on boulevard Montmartre. Within two years, the number of permanent cinemas owned by Pathé Frères affiliates throughout France and Belgium totalled 200. Soon, Pathé branches opened across Europe, with the addition of Australia, Japan and New York City. Prior to the outbreak of World War I, an estimated 60 per cent of all films were shot with Pathé equipment.

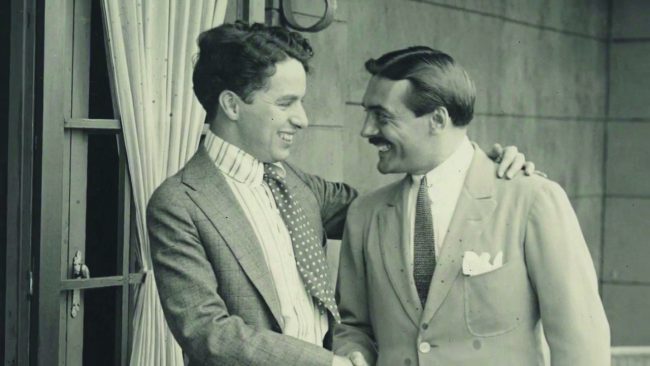

Linder and Charlie Chaplin – Linder’s character was said to have inspired Chaplin’s ‘Little Tramp.’ 1917. BFI

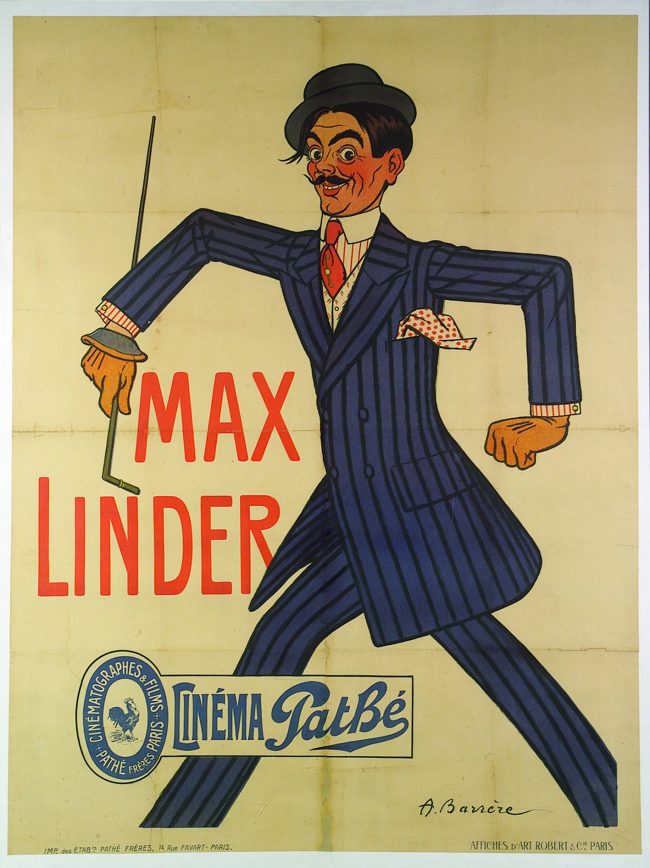

Pathé’s actors became the world’s first film stars. A face familiar to silent film audiences was Max Linder. This Parisian inspiration for Charlie Chaplin’s ‘Little Tramp’ character appeared in many films playing the role of ‘everyman’ in situations Linder made comical by his general bewilderment. Unlike Chaplin, the top-hatted Linder was an idle bourgeois living beyond his means. Starring in one-reel comedies for Pathé, with titles like Max Takes a Bath, the character was often in hot water because of his penchant for beautiful, unattainable women. Posters by the artist Faria promoted the company’s films – many featuring Monsieur Linder – to every level of society.

Pathé’s actors became the world’s first silent film stars, including Max Linder. Affiche Adrien Barrere, c. 1910/ Pathé Foundation

Charles Pathé was bursting with commercially innovative ideas: creating movie cameras for amateurs, developing non-flammable celluloid and introducing the first films in colour – hand-painted frame by frame at the Pathé laboratories. The reportage of current events was another of Pathé’s innovations. The first newsreel, the Pathé Journal, would long remain a fixture of cinemas including those in the UK where, in 1910, the pioneer newsreel was introduced as British Pathé. Archival footage includes scenes from the Boer War, rare moving images of Queen Victoria and the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. Pathé began to expand internationally, establishing branch offices in major cities around the world. During the First World War, the company moved its headquarters to the United States.

The company’s first cinema was the Omnia Pathé, which opened in Paris in 1906. Photo: Pathé Foundation

LOUD AND CLEAR

Pathé’s logo of a proud Gallic rooster proverbially announced a new day. “Je chante haut et clair,” the Pathé rooster crowed; as the trademark for the ‘talking machine’, it boasted that Pathé’s records played loud and clear. Lasting 103 years, the Pathé rooster is one of the oldest lm trademarks in existence. Its shadow is visible in the current Pathé logo – a revolving mobile speech bubble that contains yellow letters spelling the company name.

The interior of the Omnia Pathé Cinema, 1913, photo by Leon&Levy. Foundation Pathé

Charles retired in 1927 and Pathé limped through the Depression era without him; revenues slipping because of the influence of Hollywood’s movie-and-money-making machine and, disastrously for the francophone stars of the silent films, the arrival of the first English-language ‘talkies’. After deals and dalliances with many other industry names (including Eastman Kodak and Marconi), Pathé ended up on solid footing, scoring one of its greatest successes with the 1945 release of Les Enfants du Paradis (Children of Paradise), France’s answer to Gone with the Wind.

World War II dramatically affected the French film industry; its facilities were devastated and its markets depleted. Many players in European film production fled to Hollywood to escape persecution. Pathé could never hope to rival Hollywood’s box-office figures, but it continued to lead French cinema; the post-war generation of filmmakers were rejuvenated, riding the nouvelle vague.

an edition of the Pathé Journal featuring Jérôme Seydoux, Pathé’s head from the 1970s. Fondation Jerome Seydoux

TWO BECOME ONE

Charles Pathé died on Christmas Day 1957, in Monaco. For most of the 20th century, Gaumont (with its trademark daisy) had been in competition with Pathé, and the two companies were responsible for creating a huge audience of filmgoers. They ended their rivalry before the end of the 1960s, forming a distribution alliance – GIE Les Cinémas Pathé Gaumont – which administered their combined 600 theatres. By the mid-1970s, a new name had appeared on the French lm scene: Nicolas Seydoux, who had succeeded in acquiring majority control of Gaumont. He joined forces with his brother Jérôme (grandfather to actor Léa Seydoux) and together the siblings took full control of Pathé’s operations, with Nicolas leading Gaumont and Jérôme at the helm of Pathé.

The catalogues of Cinémathèque Gaumont and the Pathé Archives were combined in 2003, creating the largest French repository of film images, comprising a precious 14,000 hours of film. Carefully preserved is newsreel footage, documentaries, and even images left on the cutting-room floor.

Audiences in 2019 will be able to see new Pathé productions, including comedy Le Gendre de ma Vie (The Son-in-Law of My Life); Yao with Omar Sy; and Silvio et les Autres, starring the incomparable Toni Servillo.

New technologies including 3D, 4D, and even IMAX laser cinemas might be in the works for Gaumont-Pathé, but to 19th-century audiences nothing could be as exciting as a fairground picture show with the Pathé rooster crowing loud and clear.

From France Today magazine

“Les Enfants du Paradis” was one of Pathé’s most successful films. Foundation Pathé

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

By Hazel Smith

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *