Fabulous Ballets Russes

On May 19, 1909, just arrived in Paris from Russia, Sergei Diaghilev’s ballet company, with dancers Vaslav Nijinsky and Anna Pavlova, “fell like some great flaming comet” into the Théâtre du Châtelet and took the city by storm. The following spring, the second “Russian Season” was held at the Palais Garnier, arguably the most prestigious venue in Europe at the time. Le tout Paris was present at the premiere on June 4, 1910, including its greatest literary observer, Marcel Proust, who described the event as “a prodigious orgy of gleaming colors, rhythms and contrasting movements”. This time the full 45-minute version of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Shéhérazade was performed, choreographed by Michel Fokine, with sets and costumes designed by Léon Bakst. “A thrill of shocking brutality, fury and magnificence,” reported Arnold Bennett, ending with the slaughtered bodies of the seraglio’s odalisques “in all the abandoned postures of death”—a finale light years away from the Romantic ballets the audience was used to, like those painted by Edgar Degas.

A century later, that most influential and exciting ballet company of the 20th century is being celebrated by ballet companies and museums worldwide, in Sweden, Monte Carlo, the United States, Russia, Australia and, of course, Paris—the company’s birthplace, home base and reservoir of collaborators. But it is the Victoria and Albert Museum in London that has put together the most comprehensive and spectacular retrospective—Diaghilev and the Golden Age of the Ballets Russes, 1909–1929, which will run from September 25 to January 9.

It’s not as surprising a venue as it first might seem. The Ballets Russes was a peripatetic company, performing almost as often in London and Monte Carlo as in Paris. The V&A, one of the world’s greatest museums of art and design, also has an exceptional performing arts department, and its Ballets Russes collection is the world’s largest, comprising more than 300 items— proof if need be of the prominence of the company on the London scene of its day. And the V&A museum itself is a superb Victorian building, contemporary with the Imperial Russia that Diaghilev was born into and rooted in, before he took off for boundless new horizons in the West.

Born into a wealthy, aristocratic Russian family in Perm in 1872, Diaghilev studied music, art history and law, and worked as assistant to the director of the Russian Imperial Theaters in Saint Petersburg before launching his career as a ballet impresario. He formally established the Ballets Russes in Paris in 1911. But even earlier, he had a solid vision of his future. In a letter to his stepmother in 1895, he wrote: “I am first a charlatan, but full of dash; secondly, a charmer; thirdly, cheeky; fourthly, a very reasonable man with few scruples; fifthly, someone afflicted, it seems, with a complete absence of talent. And yet, I think I have found my vocation: to be a patron of the arts. For that I have everything I need except money, but that will come.”

At a time when ballet was on the decline and no more than a stale entertainment, Diaghilev’s initial interest in it was merely pragmatic— ballet was cheaper to produce than opera. But in just two decades he not only revitalized and revolutionized ballet but also elevated it to a higher plane. Every ballet company founded in years to come stemmed from the Ballets Russes or Diaghilev’s legacy.

Launched in the midst of the Modernist revolution, the Ballets Russes was closely linked to all the avant-garde movements of its era—Art Nouveau and Art Deco, Fauvism, Cubism, even Surrealism. It also had an enormous impact on interior design and on the world of fashion—Jeanne Paquin, Sonia Delaunay, Natalia Goncharova and Coco Chanel were all inspired by and contributed to the Ballets Russes. The influence of Bakst on his contemporary, the celebrated couturier Paul Poiret, was clear, but even as recently as 1976 Yves Saint Laurent’s Russian collection was a tribute to the Ballets Russes.

The company’s music was provided by Stravinsky, Debussy, Ravel, Satie, Prokofiev and, less successfully, by Marcel Proust’s lover Reynaldo Hahn. Librettos came from Mallarmé and Cocteau, set designs and costumes from Bakst, Alexandre Benois and Nicolas Roerich early on, and later from Picasso, Braque, Chanel and Goncharova. Matisse, on the other hand, was put off by Diaghilev’s machinations and yielded to his manipulations just once—his designs and some of the original costumes for Stravinsky’s Le Chant du Rossignol (The Nightingale) are included in the V&A exhibit. Such teaming up of stupendous talents had never been achieved before, and it allowed Diaghilev to fulfill his artistic and Wagnerian ideal of Gesamtkunstwerk (total art)—the creation of ballets in which dance, music, art and design were fused. Equally modern in concept was his desire to draw on every source of civilization, both ancient and contemporary, making him the forerunner of globalized multi-culturalism.

The Ballets Russes marked a break from the classical tradition pioneered in Russia by French dancer and choreographer Marius Petipa. Blazing hues replaced white tutus, exoticism and voluptuous eroticism were substituted for acrobatic legwork, graceful motions gave way to aggressive sensuality; torsos were freed of their corsets, feet were uncased—a trend already introduced a few years earlier by Loïe Fuller and Isadora Duncan.

In line with Diaghilev’s homosexuality, stardom shifted to male dancers. In 1911, Vaslav Nijinsky, “more nude than nude” in his body stocking in the title role of Debussy’s L’Après-Midi d’un Faune (Afternoon of a Faun), shocked many in the audience (though by no means everyone) when he mimed a sexual encounter with a nymph’s scarf; in his revealing costume, he presented “a body deliberately contrived to be bestial, hideous when seen from the front, and still more hideous in profile,” wrote Le Figaro’s Gaston Calmette.

The premiere of Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rite of Spring) in May 1913 turned into a riot, the greatest scandale recorded in ballet history. It was Nijinsky’s choreography for Stravinsky’s dissonant music that baffled this time—no grace, no melody, no story, just the savage stamping of feet by disarticulated bodies wrapped in what seemed to be bathrobes! Amidst the catcalls, boos, insults and general racket—and Nijinsky’s desperate but vain attempts to stamp and shout out the beat for the dancers—only Pierre Monteux, conducting the orchestra, remained imperturbable, “as thick-skinned as a crocodile”. (Nine of Nicolas Roerich’s spectacular costumes for Le Sacre are in the V&A show.)

Le Sacre inaugurated the company’s new venue at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées on the Avenue Montaigne. The “temple of modernity” built by architect Auguste Perret for Diaghilev’s collaborator Gabriel Astruc was the first public building in Paris made of reinforced concrete. With its pure marble-clad facade, enhanced by Antoine Bourdelle’s sculpted reliefs, it remains the city’s ultimate jewel of Modernist architecture (alas, now topped by an added rooftop restaurant).

But the Ballets Russes was an elitist venture, created for and funded by the privileged. A brilliant and visionary impresario, Diaghilev used the tools of modern marketing, coupled with his legendary charm, to raise funds from wealthy sponsors, usually women—in Paris, the Princesse Edmond de Polignac (the American Winnaretta Singer, an heiress of the Singer sewing machine family), the Comtesse de Greffulhe (the model for Proust’s Duchesse de Guermantes), and the Polish-Russian pianist Misia Sert; in London, there was the Marquess of Ripon. It is hardly surprising that the anti-establishment Surrealists shunned the Ballets Russes. George Antheil was vehemently critical of Stravinsky’s music, and André Breton and friends caused a major eruption in the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées during a performance of Roméo et Juliette with sets by the “traitors” Max Ernst and Joan Miró.

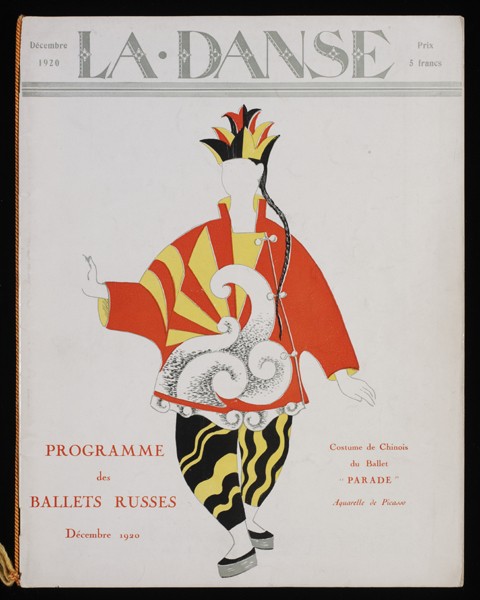

Produced in 1917, Parade was the first “Cubist” ballet, choreographed by Léonide Massine to a libretto by Jean Cocteau and music by Erik Satie, with wacky sets and costumes by Picasso. It was a golden opportunity offered to the painter by Diaghilev, during the meager war years when avant-garde art was not selling. (Picasso also met his first wife, Diaghilev dancer Olga Khokhlova.) Satie’s music got a scathing review by critic Jean Poueigh, to whom the composer responded, on a postcard: “Dear Sir and friend, you are but an ass, an ass without music.” The insult led to a court case, a prison sentence and a fine, and it was Winnaretta de Polignac who generously bailed Satie out. One of Picasso’s Parade costumes, a glowing appliquéd gown for the Chinese Conjurer character, is included in the V&A show—recovered from a trunk in Poland, where it was buried during World War II.

Picasso continued to design sets and costumes for several other Ballets Russes productions, including an enormous curtain for the 1924 Le Train Bleu (The Blue Train) that is one of the major highlights of the V&A exhibit. (It was another Gesamtkunstwerk: music by Darius Milhaud, choreography by Bronislava Nijinska—the dancer’s sister— and costumes by Chanel.)

Among other gems of the exhibit are Natalia Goncharova’s sumptuous backdrop for L’Oiseau de Feu (The Firebird), a fragile cloth that rarely goes on display; Feodor Chaliapin’s magnificent costume for the opera Boris Godunov; Nijinsky’s gold and pearl tunic for Le Festin (The Feast) from the historic 1909 season in Paris; Chanel’s chic beach costumes for Le Train Bleu; de Chirico’s costumes for Le Bal (The Ball) and a wealth of costumes designed by Bakst. Memorabilia include music scores, notably by Stravinsky, and Nijinsky’s notations for L’Après-Midi d’un Faune, displayed for the first time.

Diaghilev died at the Grand Hotel in Venice on August 19, 1929, a most becoming place for the conclusion of his itinerant existence and for a burial—his coffin was transported by a funeral gondola to the cemetery island of San Michele— that embodied his ideal of beauty. “The world has come to an end,” said grieving prima ballerina Alicia Markova. Indeed, bereaved and deprived of its leader the company disbanded, but its members spread the gospel throughout the world and down the generations, keeping his legacy alive to this day.

Victoria & Albert Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7,+44.207.942.2000. £10 Sept 25–Jan 9. website

Le Sacre du Printemps, Les Ballets de Monte Carlo, Maison de la Danse, Lyon, Sept 10–14; Monte Carlo Opera, Dec 26–28

Thirza Vallois is the author of Around and About Paris, Romantic Paris and Aveyron, A Bridge to French Arcadia. Find Thirza’s books in the France Today bookstore.

Originally published in the September 2010 issue of France Today.

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *