France Reimagined: On The Road with Ernest Hemingway

War hero, womaniser, carouser… Ernest Hemingway was larger than life. Lanie Goodman unearths the man behind the legend on a journey through France

You’ve got to hand it to Ernest Hemingway. When he describes his travels in France during the mid-1920s – and then, two wars and four wives later, in the 1950s – you can feel the burning sun and the cooling waters of the Mediterranean. You’d give anything to be sipping some of the local white wine his characters liked to quaff in great abundance with their grilled fish.

During his travels between Spain and Italy, Hem had a knack of sniffing out the best little towns in southern France before anyone else had, and over the years, his powerful prose has inspired many a reader to book a flight to France. Interestingly, it took a pandemic to knock A Moveable Feast off the number one spot at Paris’s renowned English bookstore, Shakespeare and Company (replaced by Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own).

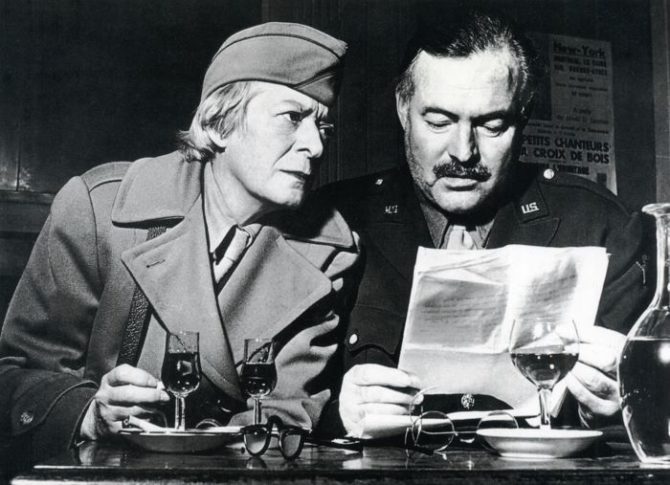

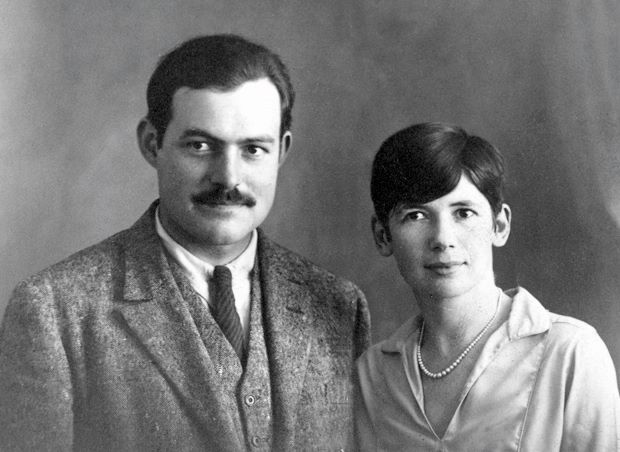

Hemmingway in Paris 1924 © JT VINTAGE/ALAMY

Of course, many readers today may object to the man himself. It is exactly 60 years since Hemingway’s suicide, and the alpha male bravado that haunts his fiction doesn’t go down quite as well as it used to. He was a brawler, a bullfight aficionado, a big game hunter, a boxer. The Key West photos of Hemingway posing with a giant marlin, puffing on a Cuban cigar made him a literary rock star. He drank like a fish and judged people on how well they could hold their liquor. He cheated on his wives and always had the next woman lined up before he left the current one. He could be cruel and vengeful, even to those once close to him like Gertrude Stein, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Gerald Murphy, all of whom had helped him when he was a struggling young writer and reporter.

And yet, there was another side to Hemingway, too: a friend to the Republicans during the Spanish Civil War, a survivor of war wounds, car accidents and plane crashes. He had courage, compassion, boundless energy and a strong work ethic. Add to that his visionary modern style and tightly crafted prose which continue to influence writers today. And judging from the popularity of the recently-aired PBS three-part docuseries Hemingway, by Ken Burns and Lynne Novick, he remains a subject of fascination.

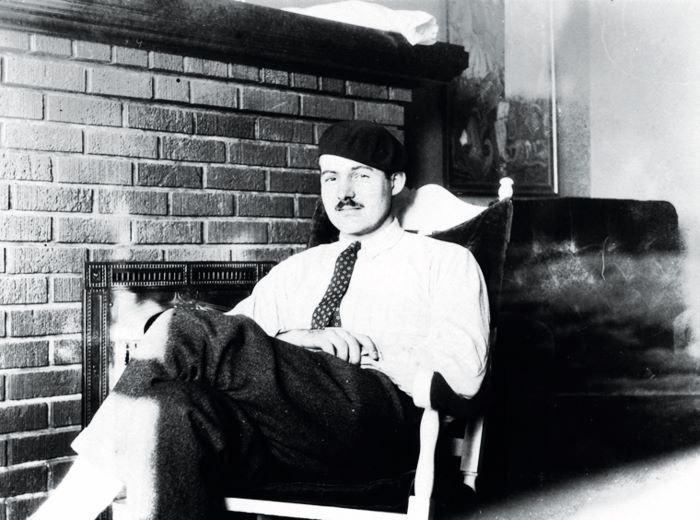

The Bar Hemingway at The Ritz in Paris © LANIE GOODMAN

TREASURE AT THE RITZ

By 1956, at age 57, Papa Hemingway had done it all. Yet, despite a Nobel and Pulitzer Prize, Hem had started to suffer from depression as his physical state started to decline. And then, a serendipitous find on a winter’s day, when Hem breezed into his old haunt, Paris’s Ritz Hotel Bar: a trunk, forgotten in a storage room since 1927, full of dusty notebooks.

Inspired by the notebook material, the ‘fictional’ memoir A Moveable Feast fondly revisits Hemingway’s early years in France. Although the tone is at times bitter, he masterfully captures the atmosphere of 1920s Paris when he lived above a sawmill at 113 Rue Notre-Dame des Champs with his wife Hadley and their baby son, Bumby. His refuge from the dark, narrow apartment and whirring saw of the lumberyard below was the La Closerie des Lilas on Boulevard du Montparnasse. These days, you can order filet de boeuf Hemingway with black pepper and Bourbon flambé at the brasserie, which is still going strong.

As newlyweds, Hem and Hadley spent their first few weeks in Paris at the Hôtel Jacob in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, now the beautifully refurbed Hôtel d’Angleterre (you can stay in his room – ask for no.14!), until they found their first apartment at 74 rue du Cardinal Lemoine, a dark, damp dump with no running water. A couple of minutes’ stroll around the corner, and just off Place de la Contrescarpe, the opening setting of A Moveable Feast, you’ll see 39 rue Descartes. Look up at the top floor: it was Hemingway’s writing room in 1922, and it’s also, allegedly, the room where poet Paul Verlaine died in 1896.

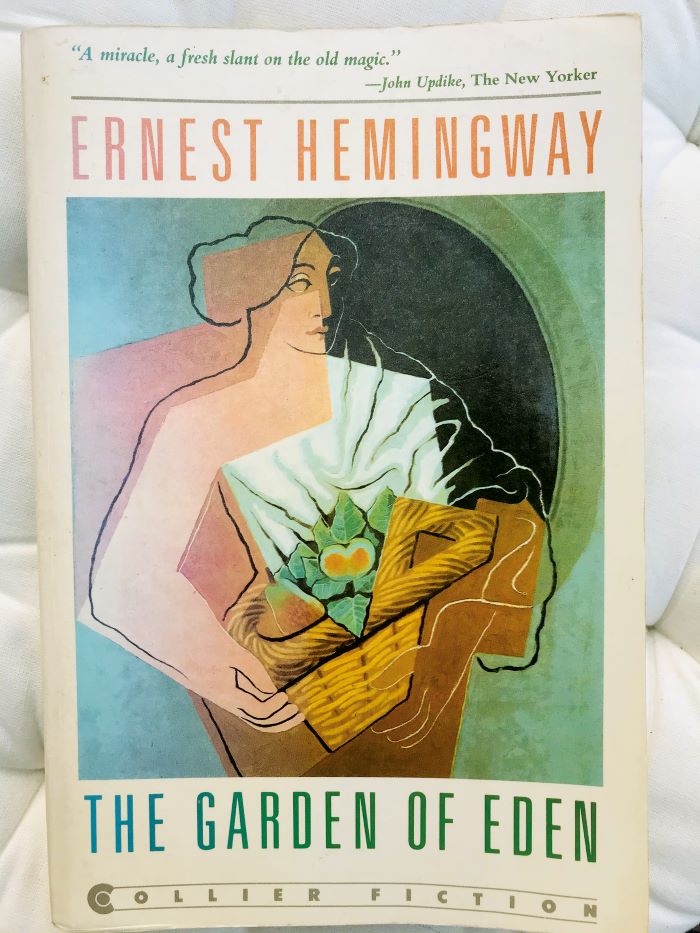

The Garden of Eden, Hemingway’s unfinished last semi-autobiographic novel, published posthumously in 1986, is set against a lush Côte d’Azur backdrop with road trips into the heart of Provence.

Here, he departs from his usual themes to explore the complexities of a love triangle and, perhaps surprisingly, gender identity. Largely inspired by Hemingway’s own troubled relationship with his first wife, Hadley, and the wealthy heiress and Vogue journalist Pauline Pfeiffer, whom he met in 1925, the novel recounts the story of David Bourne, a young American writer married to a woman who is jealous of his success, and the erotic games they play when they both fall for the same woman.

Hemingway stayed at the Imperator in Nîmes, near to the Maison Carrée © Wikimedia commons

THE ROUTE SOUTH

Over a span of more than three decades Hemingway passed through Arles (“not a place for a writer but I would love to know how to paint”), Nîmes, Avignon, Arles, Saint-Rémy, Les Baux-de-Provence, Aigues-Mortes, Le Grau-du-Roi, Aix-en-Provence, Marseille, Cannes, Juan-les-Pins, Nice and Monte Carlo. He was 25 when he made his first trip south in 1924 with Hadley; his last was at 60, a year before his death, with his fourth wife, American journalist Mary Welsh.

In The Garden of Eden, the Bournes live west of Cannes, in a “long low rose-colored Provençal house… in the pines on the Estérel side of la Napoule”. The characters spend much of their time lounging in the sun, swimming and cycling, just as Hemingway, Hadley and Pauline had done during the summer of 1926, while visiting Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald and Sara and Gerald Murphy on the Cap d’Antibes.

A copy of The Garden of Eden © Wikimedia commons

The Murphys, who served as the initial inspiration for Dick and Nicole Diver in Tender is the Night, became close friends with Hemingway and supported him during his break-up with Hadley. Gerald, an heir to the Mark Cross luxury leather goods company and visionary painter of proto-Pop Art, and Sara, a Midwestern beauty who became Picasso’s secret muse, were the Riviera’s original trendsetters, establishing their summer HQ at the Hôtel du Cap-Eden-Roc well before it was fashionable to do so.

That tumultuous July of 1926 was, in Fitzgerald’s words, “the summer of 1,000 parties”. To celebrate the publication of The Sun Also Rises, the Murphys threw a lavish party in his honour at the Juan-les-Pins casino terrace (recounted in ‘Hawks Do Not Share’ in A Moveable Feast). The Hemingways stayed at the Villa Paquita (now called Villa Picolette) in Juan-les-Pins, just down road from the seaside villa Saint-Louis, where the Fitzgeralds were living, which is now the dreamy Art Deco 5-star Hôtel Belles Rives.

Drama ensued when Pauline Pfeiffer offered to come and stay to help out with Bumby, who was ill with whooping cough… and never left. The trio moved into the pretty Hôtel de la Pinède in Juan-les-Pins, where you can still book a room today.

In The Garden of Eden, the vivid descriptions of La Camargue are reminiscent of Hemingway and Pauline’s 1927 honeymoon trip. In the secluded village of Le Grau-du-Roi, they stayed at the Grand Hôtel du Pommier (called Hôtel Grande Bellevue today), where Hem wrote some of his best short stories.

Ernest and Pauline Hemingway (née Pfeiffer) in Paris in 1927 © wikimedia commons

As in the novel, the couple also spent time in Aigues-Mortes and Avignon, and wanted to cycle from there to the Pont du Gard. “But the mistral was blowing so they rode with the mistral down to Nîmes and stayed there at the Imperator…”, an elegant Art Deco hotel that later became the haunt of famous bullfighters and where Hem would return with Mary in 1949. The hotel was recently refurbished and is now home to Duende, a Michelin-star Pierre Gagnaire restaurant. If you’re in Nîmes, stop at the Imperator’s Hemingway Bar and order a Bloody Mary – which the writer claims to have invented in order to trick the watchful eye of his wife Mary, since alcohol was forbidden by his doctors.

“Imagination,” wrote Hemingway, “is the one thing beside honesty that a good writer must have. The more he learns from experience the more he can imagine.”

From France Today magazine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

More in Cap d’Antibes, Hemmingways women, History of Hemmingway, The Garden of Eden

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY

REPLY