Surviving Provence: Food for Thought (and the Wine to Go With It)

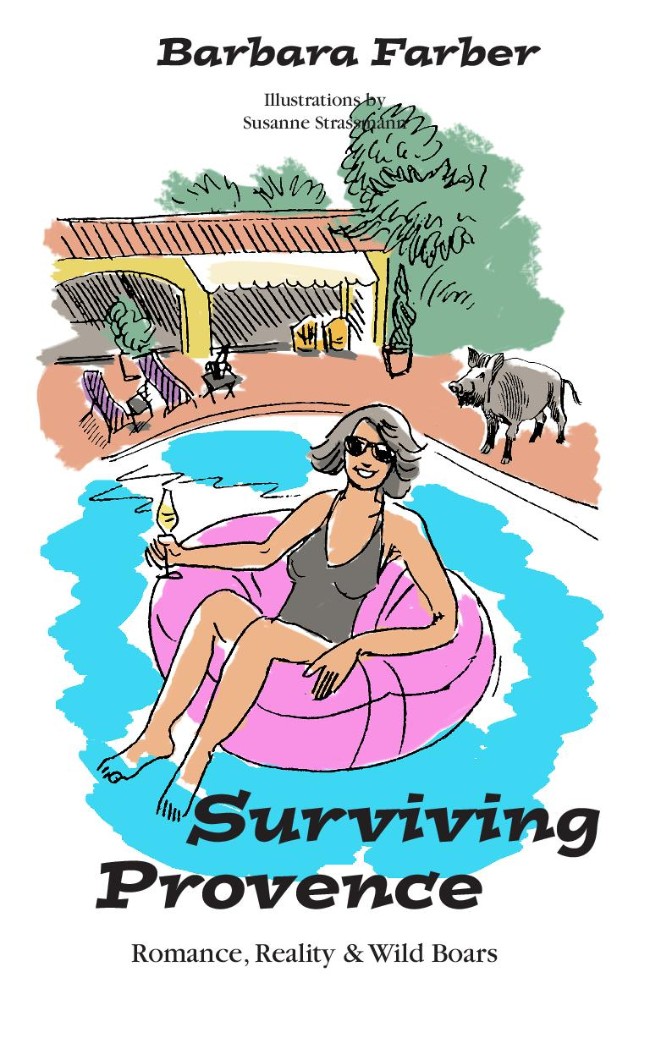

Provence is the place of dreams… until reality sets in. Taking place beneath the Montagne Ste. Victoire in Cézanne country, “Surviving Provence: Romance, Reality and Wild Boars” is a funny, sometimes acerbic, tale of life in the south of France. Author Barbara Farber uprooted her life in cozy, densely packed Amsterdam and landed amidst acres of vineyards in a “Chateau” where the front hall is bigger than her former living room. She meets a colorful cast of characters, like the chicken man at the local market who scolds her for not reserving one of his roasted delicacies in advance. The below excerpt captures the spirit of the book.

“Surviving Provence is a wonderful, personal experience of what France and Provence are about, written with humor and a sympathetic view of the foibles of the characters who play a role in the story,” says Poppy Salinger, director of La Bastide Rose, a B&B in Provence, with its Musée Pierre Salinger.

Purchase the book on Amazon below:

After the weather, food is probably the most popular topic of conversation in France, nowhere more so than in Provence. Next comes wine. Or maybe it is the other way around. It may be the only country in the world where the farmer’s wife can whip up a gourmet paté de foie gras and the farmer will know exactly what wine to drink with it.

Illustration from “Surviving Provence” by Barbara Farber, illustration by Susanne Strassmann

Dinner party discussions revolve around what one is eating, drinking, advice on how one of the guest’s great grandmothers prepared the same dish, what one ate yesterday, the new chef at the local restaurant, the appalling lack of a good cheese shop in the village, the excellent rosé at one of the nearby vineyards and the lousy white at another. Politics, business, and money being taboo, one would think food and wine were safe subjects. Ah but non! Passionate debates on what Bourgogne one should use in a daube provençal (beef stew) version of bœuf bourguignon have been known to end up in blows, but I think this is a bit of French folklore. Talking about soufflés may make tempers rise as high as this delicacy. The drinking of a glass of wine can set off an hour’s round table of opinions. The expertness with which not only men, but the women too, discuss this staple of French life never ceases to amaze me.

Manners at a French dinner party don’t count for much. A bread and butter plate or waiting until everyone has been served before raising your own fork is not the French way. Bread is broken on the table, resulting in millions of crumbs, food is downed the minute it is put on your plate and no real Frenchman waits to try the wine — sniffing it, sloshing it around and drinking, without regard to his neighbor who may still have an empty glass. But this natural approach is inbred in a people who have such an important culture of food and wine. Enjoyment is the top priority. Who wants to eat their gigot (roast leg of lamb) cold, waiting for 10 other people to get their portion.

“Bon appétit” before beginning a meal is considered very bourgeois and “not done.” Having noted this — in less exalted circles people do say “Salut”, and give a friendly tap to your glass. Dinner parties are one thing. Lunch is another world, especially here in the South where the sky is blue, the sun shines, the light shimmers and time has no meaning. A typical Provençal Sunday repast lasts about 5 hours but can be longer in summer. We are quite famous for our “dejeuners d’éte” (summer lunches) — nothing to do with my quasi French, American, Chinese cuisine but for the huge platanes shading our enormous gravelled terrace. On a hot July afternoon, I could serve bread and water and no one would complain, sitting in the cool shade of the trees, gazing at the Montagne Ste. Victoire and listening to the cigalles (cicadas). Of course, I don’t. We drink champagne and rosé, eat cold gazpacho with spicy shrimp and octopus, barbecued dorade and big fat stuffed tomatoes which I can never believe really grew in my garden. There’s an array of cheese, not of course from our village, but from the market in Aix. My favorite is a creamy St. Felicien which is probably 100% milk fat and could give a real zing to anyone’s cholesterol. For dessert, huge deep red strawberries from Carpentras, a town which has the monopoly on the best strawberries in the region. Strawberries, despite heroic efforts of our guardian, refuse to grow “chez nous”.

Illustration from “Surviving Provence” by Barbara Farber, illustration by Susanne Strassmann

Food markets herald the seasons in Provence. White and yellow peaches, sweet orange melons from Cavaillon mean summer. Asparagus and strawberries are to be eaten when the sun is high. Of course, like everywhere in the western world, you can have cherries in December, mangoes all year, melons in the winter but I cannot get used to this. It’s like drinking pastis in New York.

In Autumn huge pumpkins appear everywhere. Mine are turned into soup made with coconut milk or in chunks roasted with olive oil and garlic. The variety of mushrooms is hallucinating and local legend has it that if you pick and eat the wrong ones you can hallucinate into your grave. Cepes, girolles, sanguine, pleurotte, (pleurer means to cry in French and I wonder if these are weeping mushrooms). Admittedly, none of these come cheap but as I tell J, “filet mignon is expensive too.”

From the first of November on, stands pop up all over the villages, hawking (and shucking) oysters. Thank heaven for the last since J has not managed to master this art. Often driving home from Aix early in the evening, we stop at our favourite oyster vendor and pick up two dozen. Oysters, dark bread, a juicy lemon and a glass of white wine from the chateau next door makes cooking dinner totally superfluous. Sometimes I feel very decadent. Oysters were a delicacy one ate on special occasions, expensive and chic. Sitting in front of the TV casually devouring oysters we bought on the way home is something else. But it is the French way.

Oysters, foie gras and truffles are not considered extravagant food choices in the weeks before, during and after Christmas. Every self-respecting French woman knows how to prepare foie gras. Give her the whole goose or duck liver and in no time, she has prepared paté de foie gras aux truffes, with cognac, en croute, in a terrine with oranges and figues, or just pure with fleur de sel. For me it is still an unattainable goal although my friend says a 4-year-old child can do it. Certainly only a French one.. I content myself, and my guests, with the paté de foie gras offered by the local supermarket Behind the counter, there is a young girl who looks thirteen and can tell you everything you ever wanted to know about foie gras. Either duck or goose, mi-cuit (half cooked), fait a la torchon (wrapped in a sort of dish towel), where it came from — le Landes, Perigord, Alsace, le Gers, which is the best quality for the price and a recommendation for a confit of oignons to go with it. Only in France!

On the Sunday before Christmas, the small village of Rognes holds a foire des truffes. Provence produces three-quarters of the black truffles in France. It’s not for nothing they are called diamant noir (black diamond), the prices are astronomical. My first experience with the black diamond was lunch at a very chic couple’s house. The starter course was brouillades aux truffes (scrambled eggs with truffles). Maybe this helped develop my taste for truffles! When the restaurants start serving this specialty, beginning in December – although the truffle is at its best in February- I never pass it by.

Illustration from “Surviving Provence” by Barbara Farber, illustration by Susanne Strassmann

Most Provençals drink the wine of the region in all three colours. J and I often make the rounds of various local and not so local vineyards in search of the perfect red, white or rosé at a reasonable price, considering that our consumption is daily. It takes a lot of patience going from one vineyard to the other and tasting lots of really terrible wine. These expeditions are better done when the weather is warm. Most of the caves are freezing cold and you can’t just go in and leave after one gulp. It is an imperative form of politeness to listen as the owner talks with passion about his wine. And they all do. Every wine, great, mediocre or downright lousy, is the pride of its producer.

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY