Champignons de Paris: The Famous Mushroom and their City Farmers

A third-generation mushroom farmer or champignonniste, Angel Moioli has been working his underground farm for the last two decades. Despite the harsh competition from industrial mass producers which has led to the steady closures of the hundreds of Parisian mushroom farms, Monsieur Moioli certainly isn’t showing any sign of giving up. “I could produce cheap, perfectly shaped mushrooms without taste – but why would I do that?” he asks, horrified.

And indeed he’s right to continue, as his ‘Champignons de Paris’ are some of the most sought-after edible fungi in the Île-de-France region, although sadly they’re also among the last of their kind…

Champignons de Paris – otherwise known as ‘button’ or ‘portobello’ mushrooms – have been big business for centuries. They were first cultivated in the capital and are now grown around the world. Although people have always eaten wild mushrooms, the turning point for the industry came in the 17th century, as a result of King Louis XIV’s taste for the then rare Champignon de Paris. Farmers in the region strove to please ‘Le Roi-Soleil’ by trying to find ways of cultivating as many of the precious mushrooms as possible.

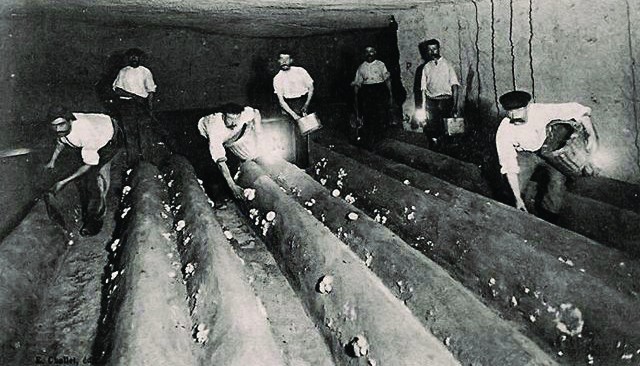

Moioli, the keenest of champignonnistes, explains that the story of Champignons de Paris began with Paris quarry workers in the city’s catacombs or, more precisely, their horses. Standing outside the quarries, these hardy steeds would leave piles of manure in which champignons would grow, as a result of wild mushroom spores being blown over from nearby woodlands. When the workers realised that they could cultivate the fungi with relatively little effort, a more formal operation began. Unfortunately, harvesting was impossible through the cold winter months – until one day, when the tale has it that a certain Monsieur Chambry, who’s said to have been a farmer for the King, had the idea of bringing the piles of manure inside the quarries, where the temperature remained more or less constant throughout the year.

From that moment on, Champignons de Paris were able to grow year-around but it wasn’t until the 19th century, when cement became widely used and stone was no longer needed, that the catacombs were completely abandoned and were able to be replaced with dedicated mushroom farms, or champignonnières. By 1880 there were over 300 mushroom farms in Paris and their trade continued to flourish until the city’s Métro network was built.

After that, the champignonnières were forced to move outside the Paris catacombs, and set up in the region’s abandoned quarries. It’s around this time that Angel Moioli’s grandfather, who was a champignonniste himself, purchased the Carrières de Montesson, about an hour out of central Paris.

“When he retired, my grandfather jumped at the chance to buy the quarry,” Angel Moioli explains, “in the hope that one of his grandchildren would work it as a champignonnière and continue the family’s legacy.”

Sadly, since the Millennium, the Île-de-France’s underground champignonnières have been closing one after the other. Moioli believes that there are now only five left in the region and about 30 across France.

His underground farm lies hidden at the end of a dirt road situated in a nondescript residential area. Once on-site, a small footpath takes visitors to the entrance of the quarry, which is barred with a heavy door, to seal in the warmth and darkness. Inside, it’s a constant 15-16°C and the humid rock passageways are lit only by the dim glow of lamps which hang haphazardly on the walls. It’s a tranquil but particular life down here. “People think I am crazy to dedicate my life to growing mushrooms, spending hours on end alone in the dark,” say Moioli, “but it’s my passion and I regret nothing.”

Moioli works his 1,000sqm quarry alone and produces 300-400 kilograms of mushrooms each week, which he sells to locals at around €3 per kilo. He’s always cultivated both varieties of Champignons de Paris – white and brown – however, “with the competition and the evolution in people’s tastes, you have to diversify.” Therefore, he also grows pleurotes (oyster mushrooms) and shitake – during our visit he was experimenting with the flower-fingered ‘avensis’. In a separate, smaller quarry next door, Moioli also cultivates ‘blue foot’ mushrooms, which grow in a fluffy, cyan-tinged moss that resembles the lunar landscape.

The main quarry has around ten cellars, where the mushrooms grow in large metal crates which look akin to ‘queen-sized’ bunk beds placed on top of one another. “I don’t use any chemicals, everything is natural,” says Moioli, whose first step in the cultivation process takes place in the incubation room, where mycelium (mushroom spores) are mixed with horse manure and straw for two to three days, until the fungi’s ‘filaments’ start to grow.

Air heated at 65°C is blown into the crates for 24 hours, which are covered in a limestone compost, to seal in the heat and to absorb excess moisture – if it’s too humid, the roots will be drowned and won’t grow into mushrooms. Each crate then has to be watered every two-to-three days – “We’re essentially just copying nature,” Moioli admits.

Five weeks later, the crates are taken from the incubation room to the growing room where it takes about 15 days for the mushrooms to reach the point where they can be harvested. “It can be more or less, it depends on the orders I have,” Moioli explains. “For instance, some chefs want bigger mushrooms to serve stuffed with cream and garlic, so I leave them to grow longer; while others want smaller ones for salads, so I have to pick them sooner.” Moioli picks mushrooms every day from these metal crates, of which there are about 20 ready at any one time.

“For me, being a champignonniste means working underground in an actual quarry, otherwise you’re just a mushroom picker, like in the industrial greenhouses you see now,” he says. “Mushrooms have to be grown underground because they’e like sponges, in that they absorb the smell of their surroundings, which gives them their taste.”

Unfortunately, even in France, the knowledge of how food’s cultivated is being lost. “It’s funny because people have no idea how mushrooms grow,” Moioli reflects. “When I open my doors to visitors during the national Journée du Patrimoine (Heritage Day), I like to ask them how they think Champignons de Paris grow. You wouldn’t believe the answers I’ve had: some think they grow on walls, or that I lay branches down on the floor and throw fully grown mushrooms on top; I wish it were that simple! Some people even come wearing Wellington boots and everything, like they’re going on an expedition. I love sharing this savoir-faire with people, a savoir-faire that is sadly dying out.”

Although his mushrooms have always been popular, especially at the Marché de Rungis, which supplies the entire region with fresh produce, at the end of the 1990s things took a tough turn, with industrial producers selling Champignons de Paris at a fraction of Moioli’s prices. As he recalls, “One day the people at Rungis called me and said they no longer wanted my produce because others were selling perfectly shaped mushrooms that cost next to nothing – and that’s when I almost went out of business.”

He’s essentially competing with the world’s main suppliers of mushrooms – China (70 per cent), USA (7 per cent), Poland and the Netherlands (4 per cent each), with France, ironically, responsible for a slim 0.4 per cent. Thankfully, owing to local distributors, the traditional champignonnistes no longer have to depend on the major markets: “Now, Rungis is calling me back to sell my produce but I refuse”.

Distributors such as AMAP (Association pour une Agriculture Paysanne), who include Moioli’s mushrooms in their fruit and vegetable baskets delivered to subscribers, and the smaller Terra Candido, which provides restaurants with locally grown produce, have turned things around for small farmers. “These smaller structures have allowed me to keep working,” Moioli says. “I couldn’t have done anything else. I don’t want to do quantity but quality. I’d rather produce less and earn less, but at least I’m happy with what I’m doing.”

Although the Champignonnière Les Carrières is now back to running smoothly, Moioli is once again worried about the future as he has no heirs to take over the reins once he’s too old to work. “It’s a hard job and the new generation isn’t interested in getting down to it,” he says. “I suppose that will be the end of the chapter for Champignons de Paris.”

Further Info

Champignonnière Les Carrières, Avenue du Général de Gaulle / Rue Jean Macé, 78360 Montesson. Tel: +33 6 09 06 21 52. The champignonnière is only open for visits on the Journée du Patrimoine every September. Mr Moioli sells his Champignons de Paris from his quarry in Montesson year-around, Mondays- Fridays 11.00am-12.30pm & 1.30-3.00pm, Saturdays 11.00am-12.15pm & 3.00- 4.00pm. He also delivers.

Champignons de Paris Essentials: Where to eat the real deal in the City of Light…

You can sample Angel Moioli’s premium, fully organic wares at these Parisian restaurants. List supplied by Terra Candido:

Aux Deux Amis, 45 rue Oberkampf, Paris 11th, Tel: +33 1 58 30 38 13

Esquisse, 151 rue Marcadet, Paris 18th, Tel: +33 1 53 41 63 04

La Cave de l’Insolite, 30 rue de la Folie Méricourt,, Paris 11th, Tel: +33 1 53 36 08 33

Il Brigante, 14 rue du Ruisseau, Paris 18th, Tel: +33 1 44 92 72 15, (No website)

Medi Terra Néa, 13 rue du Faubourg-Montmartre, Paris 9th, Tel: +33 1 83 76 05 22

O Divin, 35 rue des Annelets, Paris 19th, Tel: +33 1 40 40 79 41

From France Today magazine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *