Pass the Pastis: A History of France’s 2nd Favourite Drink

In ancient times Dionysus and Bacchus preferred the fruit of the vine, which is understandable: they were, after all, the gods of wine. But I like to imagine that the favorite tipple of their fellow deities up there on Mount Olympus was something more akin to that other great drink of the Mediterranean basin—the anise-flavored spirit that has reached its modern apotheosis in the drink the French call pastis.

Other countries boast their own versions of this ancient drink. The Greeks call theirs ouzo, the Turks have their raki and when they’re not at loggerheads with each other the Lebanese and Syrians uncork the arak. Carrying on a tradition that allegedly began in ancient Rome, the Italians sip sweet sambuca, one of those drinks you carry home with you from vacation and subsequently wonder why. But it’s in France, and particularly the sun-drenched southern parts of the country, that this drink comes into its own.

Forget beer as a thirst-quencher or aperitif. If you’re lucky enough to be gazing out over the shimmering water of Marseille’s old port or sitting in the shade of Paul Cézanne’s favorite hangout, Les Deux Garçons in Aix-en-Provence, or just grabbing a drink at a local café, try ordering a pastis (sometimes called a pastaga in Marseille or, simply a jaune, from the spirit’s distinctive yellowy color). It will come with a carafe of deliciously cold water on the side and—if you ask—some ice cubes. First pour the water into the pastis (roughly 4 measures of water for each measure of pastis but more if you prefer) and then add the ice (for ice-last rationale, see below).

Marseille, photo: Jddmano (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], via Wikimedia Commons

So it’s a bit of a mystery why one way of saying “I’m in trouble,” in French is to declare “Je suis dans le pastis.” I guess it’s more polite than other expressions that come to mind, but I suspect it may also be an oblique reference to the drink’s shady past. Pastis, it has to be admitted, has a very dodgy ancestry including a mad aunt by the name of absinthe.

Nobody’s quite sure when she first appeared on the scene, although the ingredient that gives absinthe its name, artemisia absinthium, commonly known in English as wormwood, has been used by herbalists for centuries to treat a wide variety of ailments including rheumatism and, as the name suggests, intestinal worms. But most people agree that it was a Frenchman named Henri-Louis Pernod who popularized the drink in the 19th century after acquiring the recipe from his father-in-law. In 1805 Pernod built a distillery in Pontarlier, near the Swiss border, to produce his eponymous absinthe. The drink was soon nicknamed la fée verte, the green fairy, thanks to the coloration provided by the wormwood, and it enjoyed a steady but relatively small regional fan club. But then something happened that was to propel Pernod into the big time—the devastating phylloxera outbreak of 1860s and ’70s that killed off almost all of France’s vineyards. Denied its wine, the nation turned to absinthe for solace. This could have proved problematic since the Pernod company also depended on wine to produce the alcohol for its absinthe. But the enterprising distillers at Pontarlier switched to alcohol produced from fermented sugar beets and very soon they were ramping up production.

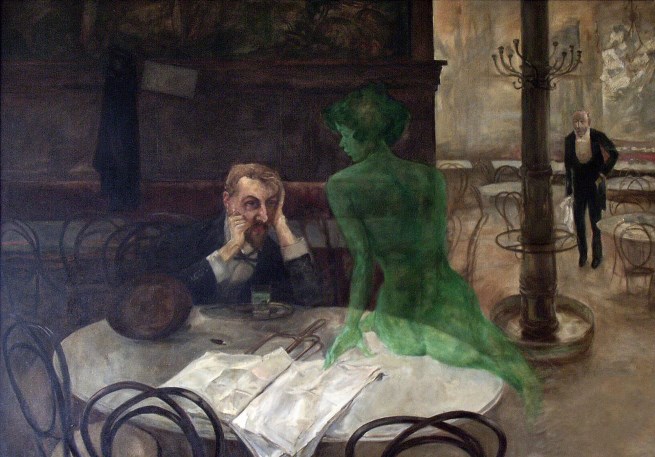

The Absinthe Drinker by Viktor Oliva, 1901

Of course it all ended in tears. France became addicted to absinthe. Visitors to the country noted in astonishment (and with a lot of tut-tutting) that the whole country would grind to a virtual halt at the end of the day for l’heure de l’absinthe or simply l’heure verte—fin-de-siècle France’s version of happy hour, in which only one drink featured on the bar bill. Absinthe cannot be blamed directly for Vincent Van Gogh‘s decision to separate one of his ears from his head, but it took the rap for the perceived or actual decadence of Oscar Wilde, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and the poets Arthur Rimbaud and Paul Verlaine—the latter poet ending up in prison in Brussels when, under the influence of the green fairy, he tried to shoot the former, his lover. The denizens of the Parisian demi-monde claimed that absinthe had hallucinogenic and other properties that made them more creative, and they couldn’t drink enough of it. “The first stage,” wrote Wilde, “is like ordinary drinking, the second when you begin to see monstrous and cruel things, but if you can persevere you will enter in upon the third stage where you see things that you want to see, wonderful, curious things.”

With friends like Wilde, absinthe scarcely needed enemies and soon it found itself, as they say, “dans le pastis“—accused of weakening the moral and physical fiber of the nation. By 1910 the French were drinking 36 million liters of absinthe a year and it wasn’t long before the anti-alcohol brigade was on the case, pressing for a ban. Although absinthe’s active ingredient—a chemical called thujone found in wormwood—is a neurotoxin in extremely high doses, modern analysis suggests that the amount of thujone present in the typical fin-de-siècle absinthe was insufficient to be a mindbender and that it was probably absinthe’s very high alcohol content—and high consumption rate—that was to blame for the drink’s ill effects and bad reputation. But the prohibitionists (ably supported by the wine lobby, which didn’t like the competition from the green fairy) carried the day and in 1915, one year into the Great War when the French probably needed a stiff drink, it was outlawed.

Fast forward to the 1920s. Absinthe was still banned but the government (probably mindful of the tax revenues that would ensue) gave the go-ahead for absinthe-style drinks to be sold provided they contained no wormwood and were not too alcoholic. A brash young entrepreneur from Marseille with a flair for marketing, Paul Ricard, decided to market an anise-flavored drink he called pastis. It was strong stuff and got Ricard into trouble with the authorities, but the French public took a shine to Ricard’s concoction, which bore his name and which he declared to be “the true pastis from Marseille,” a claim that gave the drink a certain raffish allure. By 1932 Ricard and others had managed to get the law changed to allow a higher alcohol content and a market was born. Not to be outdone, Pernod launched its own anise drink (which to this day it resolutely refuses to call a pastis) and pastis became as much a symbol of France as the beret, the baguette and boules.

The 1960s saw the drink’s apogee and since then it has been fighting to hold on against a host of other international drinks, and growing French abstentionism—or at least moderation—due in no small part to more stringent and well-enforced drunk-driving laws. At Paul Ricard’s suggestion, Pernod and Ricard joined forces in 1974, the better to confront beverage competition from overseas. The combined enterprise has gone on to become the world’s second largest drinks company, although pastis has become a shrinking part of its broad cocktail cabinet.

But, to judge from café tables here and there recently, the aroma of anise is suddenly wafting dans le vent again, and certainly there’s still plenty of it out there waiting to be savored. Ricard (with over half the market share) still sends its blenders out to China each year to inspect the star anise crop and carry out preliminary tastings to ensure quality (a role that has earned them the nickname “the long noses” among Chinese star anise farmers). Dozens of small-batch producers have sprung up, and of course the big supermarket chains all have their in-house brands. That not-so-mad aunt absinthe has also been rehabilitated and for the last ten years it has been possible once again to tipple the green fairy legally in France. It’s not as easy to find as pastis but a number of bars carry absinthe, and Pernod, the historic instigator of the 19th-century absinthe craze, is once again producing its own fée verte.

Serving pastis

The French tend to drink their pastis without ice, just water from a carafe cold enough to have beads of condensation on the outside. Pastis contains an aromatic compound called anethole that doesn’t like water (it’s hydrophobic), so when you add water to the yellowy spirit it becomes a precipitate and the pastis turns opaque—a bit like those “snow storm” ornaments which create a contained blizzard when shaken. If you add ice before you add the water, the added cold causes the anethole to precipitate as crystals, which you don’t want. So put the water in first.

Pastis cocktails

There are a good number around, but here are three:

Le Perroquet (the Parrot). Perhaps the best known and most popular of the pastis cocktails. To make it, most French bars will follow the directions for mixing pastis given above, then add a dash of mint syrup. Harry’s Bar in Paris suggests a more serious teaspoon of crème de menthe. In either case, it’s even greener than the fairy.

Le Tremblement de Terre (the Earthquake). Said to have been invented by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec: pour equal measures of whisky, pastis (or absinthe) and gin into a cocktail shaker with ice. Serve in a cocktail glass.

Death in the Afternoon. Ernest Hemingway gets the credit for this one: champagne in a flute with a dash of pastis added. Maybe this was what inspired him to “liberate” the bar at the Ritz when Paris fell to the Allies in World War II.

From the France Today archives

Why not join France Today on our tour of Provence, we’ll be stopping off at Cezanne’s favourite spots in Aix-en-Provence.

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email