Love in the Louvre

Originally published in the February 2009 issue of France Today.

Love in the Louvre, a gem in Flammarion’s Musée du Louvre series, is a charming little anthology of amour as portrayed in the museum’s masterpieces, compiled by art historians Jean Claude Bologne and Elisa de Halleux.

Some of the works are instantly recognizable, including Rembrandt’s Bathsheba at her Bath with David’s Letter (1654) and Ingres’s The Turkish Bath (1862). Classic 18th-century French works include Fragonard’s glorious The Bolt (1777), in which an ardent young lover locks the door to the bedchamber while holding his paramour in an enthusiastic embrace, and Watteau’s The Faux-Pas (c. 1716-1717), in which a man’s desire gets the better of him. Famous lovers from literature and legend are well represented: the doomed duo from Dante’s Inferno are beautifully depicted in Ary Scheffer’s The Shades of Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta Appearing to Dante and Virgil (1855), floating though hell in agony as Dante and Virgil look on; Jacques-Louis David’s Paris and Helen (1788) portrays the characters whose love affair provoked the Trojan War in an intimate moment before Helen’s abduction.

Bologne and Halleux have also made several more unusual choices, such as Man with Boy (c. 480 BC), a red-figure cup from the Classical period in which a bearded man leans over a younger boy to plant a tender kiss. On the lid of the haunting Sarcophagus of the Cerveteri Couple (Southern Etruria, c. 520-510 BC) reclines a life-size sculpture of the couple buried inside, the man’s arm draped gently over the woman’s shoulder. “Their tender gestures and serene smiles imply that they are a married couple,” writes Halleux, “now united in death for all eternity.” They look utterly content.

Some paintings render love as rather painful-Ingres’s heroines often look as if they are having no fun at all, as in Roger Delivering Angelica (1819), in which Angelica waits to be saved from a marine monster. Conversely, Johan Tobias Sergel’s sculpture Centaur Grabbing a Bacchante (c. 1775-1778) depicts the pure pleasure of lust.

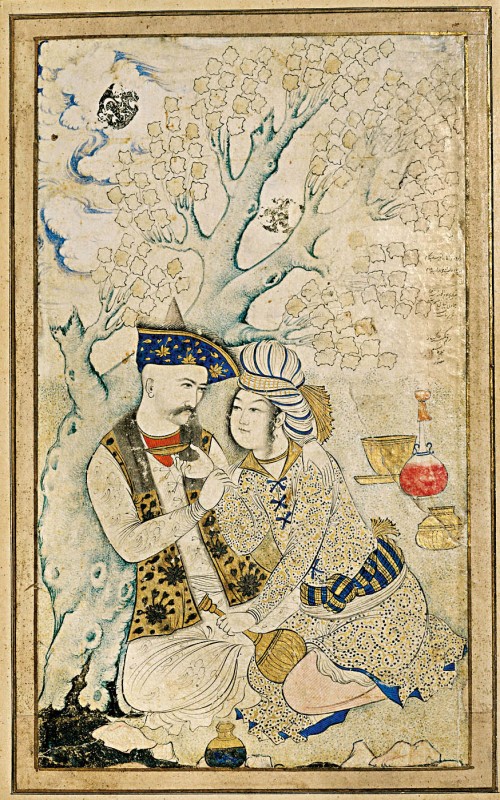

The selections in Love in the Louvre represent all the many aspects involved in what we think of as love-sex, marriage, passion, power, violence, terror, sadness, pleasure, pain. It’s a rich subject, as fascinating to the artists of ancient Persian courts as to salon sculptors of 19th-century Paris. As always, the Louvre proves an exhaustive resource, and the authors guide us carefully through, telling us where to look, noting what we might have missed. As Halleux points out, these artists invite us to witness the most private moments in human life, and no subject is as universally recognizable as love.

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email