Jefferson Amid the Ruins

On February 28, 1787, Thomas Jefferson, American minister to France, set out from Paris in his own carriage, traveling as a private citizen, “determined to be the master of my own secret”. The reason for his journey south to Aix-en-Provence was a painful right wrist, dislocated the previous fall; he wanted to see if the city’s renowned mineral waters might help him heal. But he was also a dedicated traveler. “I am constantly roving about,” he wrote Lafayette, “to see what I have never seen before and shall never see again.”

His three-month, 1,200-mile trip allowed him to savor the warmer climate, the vineyards and olive groves of the south, and it also became an edifying Enlightenment expedition. His trunk stocked with paper, pens, a portable copying press, a pocket thermometer and measuring tapes, Jefferson made careful notes about everything he saw along the way—from the kinds of firewood and the sizes of barrels to what ordinary people ate. His journey was, he wrote, “a continued feast of new objects”. As his Notes of a Tour into the Southern Parts of France, &c. indicate, Jefferson’s high “degree of curiosity” was directed toward dozens of subjects.

Not incidentally, the excursion also allowed Jefferson, a self-described “enthusiast of the arts”, to explore the remains of Roman antiquity in France. For him, “the city of Rome is actually existing in all the splendor of its empire”. Rome itself was too far away, and on his one trip to Italy he had enjoyed “a peep only into Elysium. I entered it at one door, and came out at another, having seen, as I past, only Turin, Milan, and Genoa.” But he satisfied himself with what he saw in France.

Architecture was a serious interest for Jefferson, if not a passion. A self-trained architect, he designed two houses for himself—Monticello, near Charlottesville, Virginia, and Poplar Forest, his plantation near Lynchburg. He also revised various other houses that he occupied, and made significant contributions to American architecture, especially through his designs for the Virginia State Capitol and the University of Virginia. When the Marquis de Chastellux, a philosopher and a major general who fought with French troops in the American Revolution and later wrote a book about his travels in America, visited the unfinished Monticello in 1782, he observed that “Mr. Jefferson is the first American who has consulted the Fine Arts to know how he should shelter himself from the weather”.

Jefferson’s architectural expression was grounded in the classics and an understanding of ancient architecture. Until this trip to southern France, Jefferson’s knowledge of ancient architecture came primarily from books, particularly Italian Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio’s The Four Books of Architecture, which he came to own in five different editions over his lifetime. Jefferson carefully studied what he called his “bible”, learning about the language of architecture from Palladio’s drawings of the Tuscan, Doric, Ionic and Corinthian architectural orders, ancient buildings and his own designs.

The road south

“From Lyons to Nismes I have been nourished by the remains of Roman grandeur,” Jefferson wrote (using the 18th-century spelling of Nîmes). He arrived in Lyon—the Roman Lugdunum—on March 11, stayed four days and evidently toured the remains of several Roman theaters, the foundation of a temple, and the ruins of four aqueducts. With much still to be excavated, he also noted “some feeble remains of an amphitheatre…”. He wrote William Short, his secretary in Paris, that “Architecture, painting, sculpture, antiquities, agriculture, the condition of the laboring poor fill all my moments”.

In his account of his visit to Vienne, Jefferson mentioned “the Sepulchral pyramid, a little way out of the town,” and carefully described its dimensions and features. He mentioned what he called the Pretorian palace, now known to be a temple dedicated to Emperor Augustus and his wife Livia. He favorably compared its proportions to the Maison Carrée in Nîmes—which at the time he knew only from drawings—but lamented that the temple had been “totally defaced by the Barbarians…its beautiful, fluted Corinthian columns cut out in part to make space for Gothic windows…”

Visitors to Vienne today can still see the pyramidal monument—originally part of a circus for chariot races—and the restored Temple of Augustus and Livia, with a plaque nearby marking Jefferson’s visit. Vienne’s Roman theater, not yet excavated in Jefferson’s day, is now the site of a summer jazz festival, and other Roman ruins are found throughout the city and across the river in Saint-Romain-en-Gal.

“Here begins the country of olives,” Jefferson noted about Orange, once the Roman colony of Arausio. He stopped to see the “sublime triumphal arch at the entrance into the city”, built in the 1st century BC and renowned for its rich decoration. He also saw the amphitheater before it was dismantled and its stone repurposed. Jefferson was stunned to find that they are “pulling down the circular wall of this superb remain” to pave a road. He praised a former superintendent for “the pains he took to preserve and to restore these monuments of antiquity” and criticized the present authority for “demolishing the object to make a good road to it”, as he wrote to a friend. The surviving Théâtre Antique, not fully excavated in Jefferson’s time, and the Triumphal Arch are now on UNESCO’s World Heritage List.

On his way to Nîmes, Jefferson discovered the famed Pont du Gard, the massive arched stone remains of an aqueduct that carried water some 25 miles from Uzès to Nîmes, spanning the Gardon River on its way. Jefferson pronounced it a well-preserved “sublime antiquity” and noted that wild figs grew out of its joints. Artist Hubert Robert painted it, and also the Triumphal Arch and the Theater in Orange, the same year that Jefferson visited those sites. In late August, Robert exhibited his pictures at the Salon of 1787 at the Louvre, where Jefferson praised “five pieces of antiquities by Robert”.

Temple of liberty

Perhaps the most notable stop on Jefferson’s tour was Nîmes (the Gallo-Roman Nemausus), where he paid homage to the Maison Carrée. Even before seeing it for the first time, on March 19 or 20, he believed that it “was the most perfect and precious remain of antiquity in existence. It’s superiority over any thing at Rome, in Greece, at Balbec or Palmyra is allowed on all hands”. Captivated by its perfection, he wrote to the Comtesse de Tessé (one of his favorite correspondents, she was the daughter of the Duc de Noailles and Lafayette’s aunt by marriage): “Here I am, Madam, gazing whole hours at the Maison quarrée, like a lover at his mistress. The stocking-weavers and silk spinners around it consider me as an hypochondriac Englishman, about to write with a pistol the last chapter of his history.”

Jefferson had been familiar with the Maison Carrée for years, from a plan and elevation published in Palladio’s Book IV, and in 1785 he had successfully urged the Virginia General Assembly to adopt its form for the Virginia State Capitol in Richmond. Jefferson conceived of the Capitol as a temple of liberty, and its Roman-temple design in turn inspired countless temple-fronted public buildings in the United States. To assist with the preparation of the drawings for the Capitol, Jefferson engaged a French architect and accomplished draftsman, Charles-Louis Clérisseau. On Jefferson’s instructions, Jean-Pierre Fouquet (1752–1829) crafted a plaster model at a scale of 1:60 (1 inch=5 feet) to further communicate the design to the workmen carrying out the construction.

At Nîmes Jefferson also visited the 1st-century amphitheater and, in the Jardin de la Fontaine, the Roman baths and the ruins known as the Temple of Diana. He explored the archaeological collection assembled by Jean-François Séguier (1703–1784), the noted antiquarian who had written about the Maison Carrée and supervised its excavations and restoration from 1778 to 1781. Jefferson decided that a copy of a bronze askos, an unusual pouring vessel, in Séguier’s collection would make an excellent gift for Clérisseau; he commended it for “sa singularité et sa beauté”. A wooden model of “ce charmant vase” was commissioned, but it never reached Jefferson. Clérisseau was instead sent an urn designed by Jefferson (whereabouts now unknown). In 1801, with a second model of the askos in hand, Jefferson hired Philadelphia silversmiths Simmons and Alexander to create a silver version, ultimately used at Monticello for serving hot chocolate.

Riveted by the Roman monuments he had seen, Jefferson announced to Madame de Tessé on March 20 that “Roman taste, genius, and magnificence excite ideas”. To William Short he summarized his experience, observing that these monuments “are more in number, and less injured by time than I expected, and have been to me a great treat. Those at Nismes, both in dignity and preservation, stand first. There is however at Arles an Amphitheatre as large as that of Nismes, the external walls of which from the top of the arches downwards is well preserved.” As well as the amphitheater, in Arles Jefferson also visited the Roman theater and the 11th/12th-century church and cloister of Saint Trophime. (The amphitheaters in Nîmes and Arles are both still in use for bullfights, festivals, concerts and other events; the theaters in Arles and Orange are also still used for opera and other performances.)

Gulping it down

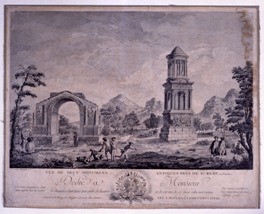

Jefferson’s enthusiasm did not wane as his trip continued. He described his routine to Lafayette: “I go to see what travelers think alone worthy of being seen; but I make a job of it, and generally gulp it down in a day.” At Saint-Rémy-de-Provence on March 24 and 25, he saw the Triumphal Arch and Mausoleum at the Roman site of Glanum, and he later owned an engraving of them, Vue de Deux Monuments Antiques prés St.-Rémy-en-Provence, 1777. That is all he was able to see in 1787—the extensive ruins of Glanum visible today were excavated between 1920 and 1970.

In the notes he prepared for American travelers in 1788, Jefferson advised that architecture merited “great attention”. He considered it “among the most important arts”, essential “to introduce taste into an art which shews so much”. Upon his return to America he followed his own advice. As a result of his study of neoclassical buildings in Paris during his years there, his fascination with the remains of Roman antiquity in southern France and his continuing self-education in architecture through books, Jefferson’s designs brought brilliantly cultivated taste to American architecture.

Susan R. Stein is the Richard Gilder Senior Curator and Vice President for Museum Programs at Monticello in Charlottesville, Virginia.

Originally published in the September 2011 issue of France Today

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *