Parisian Walkways: Rue Sainte-Anne

Just west of the Palais Royal, stretching northwards from the 1st arrondissement into the 2nd, Jeffrey T Iverson discovers a street where globalisation has a positively benign face…

Critics such as the historian Andrew Hussey, author of Paris, A Secret History, have been railing since the turn of the 21st century against what has been called the muséification (museumification) of Paris, as the historic centre of the capital keeps losing residents and small businesses to rising rents, and entire districts are invaded by big brands and tourist shops. But not every street in the heart of Paris has necessarily lost its sense of history and identity.

Just west of Palais Royal is one that seems to have always been inhabited by people slightly ahead of their time and which today has in many ways become a symbol of the most delicious, diversifying effects of globalisation: rue Sainte-Anne.

“It’s a street which people have come to love because it offers the chance to travel in so many ways,” says Sandrine Donvale, manager of the transporting spice shop at No. 51 bis, Épices Roellinger. “Through the aromas of spices, the flavours of cuisines, but also in the pages of books and through objects imported from around the world, rue Sainte-Anne is a place for voyages of the senses of every kind.”

Épices Roellinger. Photo: Frederic Baron

Situated in the first and second arrondissements between avenue de l’Opéra and rue Saint-Augustin, this ancient street, first referred to by the name Sainte-Anne in 1633, has been home to many men and women who marked their centuries. From the unscrupulous Comte Jean-Baptiste du Barry at 34 rue Sainte-Anne, who sought influence by making his lover Jeanne Bécu the mistress of Louis XV, to the poet Charles Baudelaire, who lived for part of 1854 at No. 61 in the Hôtel d’York – today named Hôtel Baudelaire. It was even here at, No. 53, that in 1822 the merchant Louis Nicolas revolutionised the wine trade by opening the first shop selling wine by the bottle instead of by the barrel.

But it was in the 20th century that the street truly gained a reputation as a bastion of the avant-garde, and a bellwether of France’s evolving society. In 1932, the French singer and cabaret star Suzy Solidor chose 12 rue Sainte-Anne to open La Vie Parisienne, perhaps the first nightclub owned by a woman in Paris. Openly lesbian, Solidor was known as ‘the most painted woman in the world’, having sat for some 225 artists from Tamara de Lempicka and Francis Bacon to Jean Cocteau and Man Ray.

“Solidor was a woman ahead of her time,” wrote Holly Williams for the BBC. “She matched a risqué artistic persona with shrewd business acumen, and possessed a striking awareness of the power of propagating her own image. Consider Solidor a 1930s Kardashian, with painterly portraits in place of selfies.” By the late 1960s and early 1970s, rue Sainte-Anne had become a veritable playground for the gay, young and artistic communities of Paris, gathering in nightclubs like The Colony at No. 3 or The Bronx at No. 11.

Street art by Invader adorns the intersection of rue Sainte- Anne with rue Thérèse, the heart of Little Tokyo in Paris. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

In 1970, Japanese-born fashion designer Kenzo Takada opened his first boutique in Passage Choiseul, the covered arcade running parallel to rue Sainte-Anne, and connected to it by the Passage Sainte-Anne. Takada recalled in the Asian Review the time he spent in the 1970s with fellow designers Yves Saint Laurent and Karl Lagerfeld at the disco Le Sept, opened in 1968 at 7 rue Sainte-Anne. “The three of us were regulars there,” he wrote. “Besides those of us in the fashion world, artists and entertainers hung out there as well. The likes of Mick Jagger, Sylvie Vartan and Andy Warhol regularly came and went. It was also the hub of Paris’s gay culture. To succeed in Paris, it was extremely important to be part of the nightlife scene. We would drink toast after toast of Champagne and wine and dance until dawn. It was there that our personal connections grew, new business was born and the seeds of love were sown.”

Le Sept closed in 1980 when the gay community began migrating to the Marais. By then, Kenzo’s infusion of Japanese, Bengali, and African influences into European haute couture had rocked the Parisian fashion world, and he’d moved his growing empire to more chic quartiers. Yet this worldly entrepreneur’s stint in the rue Sainte-Anne neighbourhood was a herald of the street’s next transformation.

Japanese rice cake by Aki Boulanger

Serge Lee, who was born in Japan to Korean parents, came to rue Sainte-Anne 12 years ago, where he has since opened the Japanese restaurant Aki (No. 11 bis), Aki Café (No. 75), Aki Boulanger (No. 16) and Sapporo ramen bar (No. 37). “In the 1980s and 1990s, there were a lot of Japanese tourists in France, even more than today,” he says. “Which is why there started to be a lot of travel agencies and duty-free shopping around the quartier Opéra. So when the gay community began to leave rue Sainte-Anne, a few small Japanese businesses, shops and travel agencies began to open up here. Then, after the 1990s, when the street had entirely emptied out, Japanese restaurants started to open up too, and the street really began to evolve. This core of Japanese businesses on rue Sainte-Anne expanded to the streets all around. Now they call it Little Tokyo in Paris.”

After first welcoming travel businesses like Vivre le Japon at No. 30, the first Japanese travel agency in France, founded in 1981, rue Sainte-Anne began to see the arrival of many more global travel agencies as well. One of the earliest was the travel agency Voyageurs du Monde, which opened its first cité des voyageurs in 1994 at No. 55, offering travellers made-to-measure trips created in consultation with an expert on their destination of interest to fit their budget and desires.

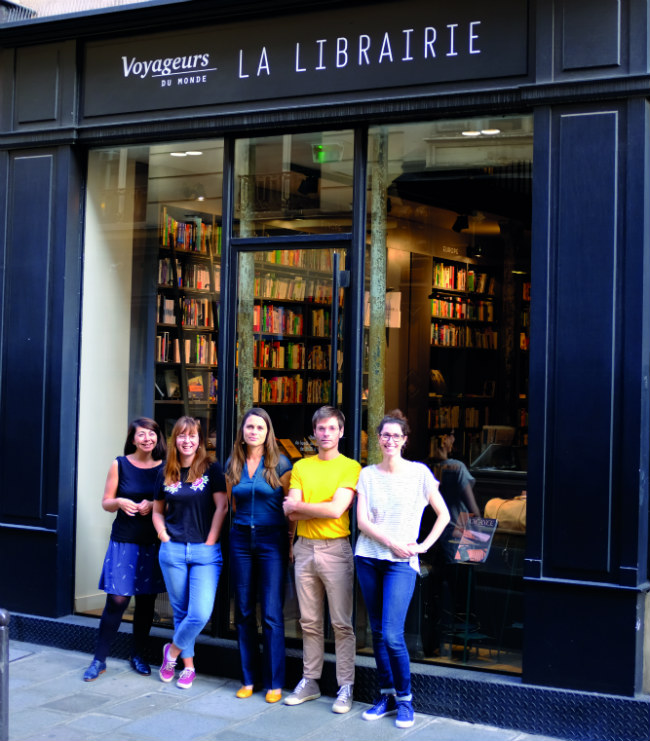

Librairie Voyageurs du Monde. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

Five years ago, the agency created another resource for their clients by opening Librairie Voyageurs du Monde at No. 48. Lisa Fiquet, who today runs this wonderful travel bookstore, jumped at the chance to be part of it. “I’ve always been interested in travel, after all I’m part of a generation raised on images from the four corners of the world,” she says. “This is a bookstore for preparing every kind of voyage – physical voyages, but also the cultural voyage you experience in another country, and the voyage we take through the pages of a transporting novel or photography book.” Among its 14,000 resources, including travel guides, memoirs and fiction organised by destination, is an enormous collection of maps, with everything from US Air Force aerial charts to historical maps of sunken Spanish galleons, to maps of the most isolated reaches of Nepal and Patagonia. But as Fiquet notes, there are adventures awaiting just outside her door. “It’s a unique advantage to have a travel bookstore on a street where even during your lunch break you can travel to the four corners of the world, just by visiting the restaurants and shops here! We’re in a very cosmopolitan street, it’s an environment rich with the spirit of travel.”

Epices Rœllinger. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

That spirit perfumes the air at Épices Roellinger, opened in 2011 after Jean-François Rial, the co-director of Voyageurs du Monde, offered his friend, the Breton chef Olivier Roellinger, use of a locale next door to his agency. Roellinger shocked the gastronomic world in 2008 when he gave back his three stars and closed his fine-dining restaurant in Cancale. But instead of retiring he decided to set sail in the spirit of the spice hunters who brought back turmeric and star anise to the Breton port of Saint-Malo centuries ago, and to import these treasures himself. His spice boutique on rue Sainte-Anne is his first in Paris, decorated with maritime maps, an old chest overflowing with spices, and an 1825 frigate made entirely of cloves. Colourful bottles of spices and oils line the walls. Sandrine, Romain and the rest of the team advise clients on how to enliven a chocolate ganache with Sichuan peppercorn, or create a custard with a grand cru Madagascan vanilla clove. Indeed, Épices Roellinger, like the chef’s cuisine, is a celebration of the globalisation of flavours that the spice hunters initiated centuries ago when they first brought these magical powders and herbs back to France.

Olivier Roellinger at the Épices Roellinger boutique. Photo: Benoît Teillet

For Romain, who came to Épices Roellinger one and a half years ago, discovering how globalisation continues to play out on rue Sainte-Anne is part of the pleasure of his job. “It’s a street in constant movement; it’s constantly changing,” he enthuses. “What surprises you about rue Sainte-Anne are the mixes that happen here. I think this cultural mélange is really what makes this street so interesting.”

The bakery and pastry shop Aki Boulanger was created in 2010 with exactly such a goal in mind. “Japanese pastries are perfumed with ingredients like matcha tea or sweet azuki red bean paste,” says Aki pastry chef Fumiyo Takahashi. “And so, in addition to our authentic Japanese breads, I’ve used those kinds of ingredients to create a marriage between Japanese and French pastry, such as our now famous matcha tea or azuki-marbled brioches, and our green tea or yuzu éclairs. First there was only a lot of Japanese clientele, then bit by bit the French started to come. After a year, the clientele was mixed half and half.”

Cheese at Fromagerie Hisada. Photo: Jefffrey T Iverson

CURIOUS GASTRONOMES

Aki has received further waves of curious gastronomes since Naomi Kawase’s Japanese film Sweet Bean (Les Délices de Tokyo), dedicated to the traditional red-bean pancake dorayaki, premiered at Cannes in 2015. So has the tearoom Tomo, nearby at 11 rue Chabanais, now heralded as the ‘dorayaki temple’ of Paris. Likewise, Eri Hisada, of the Japanese cheese shop Fromagerie Hisada, is convinced that the rue Sainte-Anne neighbourhood has become a true destination for adventurous foodies.

“Here, we have so many clients that are interested in tasting new cheeses and foreign cheeses,” says the maître fromagère. “We visit farms all over France and Europe; we’re always looking for new cheeses. Today we have about 80 per cent traditional French cheeses, but also 20 per cent foreign cheeses, and our own original creations.” These award-winning delicacies include chèvre with wasabi, yuzu or aged with cherry blossom; Brillat-Savarin infused with matcha tea and quince paste; Parmesan aged in Nikka whisky, Taleggio aged with sake…

Fromagerie Hisada. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

When the owner of an artisan French butcher’s shop at 58 rue Sainte-Anne was ready to retire in 2014, the neighbourhood might have lost a generations-old business for good. Instead, the owners of the Korean market ACE Mart across the street gave it a new life. They focused on high-quality French beef, and foreign breeds like Wagyu and Angus, while adding a range of traditional Korean dishes made from fresh seasonal produce from their market. It was an instant success.

“These businesses of the rue Saint-Anne have really found a harmony with the neighbourhood,” says Hyegyong Jin, who runs Boucherie ACE with her chef Sungnam Kim. “In the beginning, all this was very new for French people, but then they tasted it and really enjoyed it, and soon we were having 150-200 people a day for lunch. It’s incredible for us, but I think it’s because this street is now truly international, and today people know rue Sainte-Anne is a place where they can always go on an adventure.”

Ace Boucherie. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

ADDRESSES

Ace Boucherie, 58 rue Sainte-Anne, Tel.+33 1 42 96 68 09

Ace Boucherie was created to provide high-quality meat to the clientele of the Korean market across the street. Their Wagyu and Angus beef is top grade, like their marinated meats and special thin cuts for Korean barbecue and Japanese cuisine. But the queue running down the street at lunchtime is for their deli, offering homemade take-away dishes from seasonal produce.

Bottles, 57 rue Sainte-Anne, Tel. +33 1 42 61 93 90

Benoît Dechelette opened his wine bar to show why his native Lyon is France’s gastronomic capital: it’s bordered on all sides by regions rich with unique terroirs – Beaujolais, Burgundy, Savoie, Rhône – all yielding an abundance of distinctive wines and products. Wines from ancient estates and biodynamic trailblazers are paired with farm- fresh charcuterie, cheese and other delicacies.

Benoît Dechelette at Bottles Wine Bar. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

Épices Roellinger, 51 bis rue Sainte-Anne, Tel. +33 1 42 60 46 88

This spice shop is the result of decades of research and travel by the chef Olivier Roellinger, who studied the history of the spice trade that once flourished in the port city of Saint-Malo to create a revolutionary French cuisine infused with flavours of the world. Discover Roellinger’s selection of rare peppers, grand cru vanillas, and signature, ready-to-use spice blends.

Librairie Voyageurs du Monde, 48 rue Sainte-Anne, Tel. +33 1 42 86 17 38

In five years, this spacious librairie has gained a reputation as one of the most comprehensive travel bookstores in the capital, offering everything you need to prepare your voyage, from travel guides – and perhaps the largest selection of world maps in Paris – to literature, travel essays and graphic novels.

Fromagerie Hisada, 47 rue de Richelieu, Tel.+33 1 42 60 78 48

The first Paris boutique and tasting room from Japan’s undisputed queen of cheese Sanae Hisada, this Franco-Japanese fromagerie offers all the exotic creations and unique fusions of the two cultures that you might expect. But if people come first for Hisada’s curiosities, they soon come back for the stunning quality and flavour of her most basic Camembert or her truffled Mont d’Or.

Bottles Wine Bar. Photo: Jeffrey T Iverson

Aki Boulanger, 16 rue Sainte-Anne, Tel. +33 1 40 15 63 38

In 2010, the owners of the Japanese restaurant Aki came up with an inspired concept: to create a Franco-Japanese bakery where Japanese expats can find a taste of home in traditional Japanese breads and pastries like dorayaki crêpes, and where curious French foodies can also come to taste brioches infused with sweet azuki red bean paste or éclairs flavoured with green tea or yuzu.

From France Today magazine

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY

REPLY