Great Destinations: Limousin, Land of Fire and Stone

Colourful villages, masses of châteaux and wonderful local stone – a Limousin road trip is an exciting way to see the delights of this rural and sparsely-populated region. Hit the Route Richard Coeur de Lion, or just follow your nose. Jon Palmer is in the driving seat.

Spireless, the Limoges cathedral overlooks the Vienne river. © Ville de Limoges/ Thierry Laporte

On a Saturday night in February last year, a fire broke out on the rue de la Boucherie, in the vieille ville of Limoges. This is in the city’s medieval district, where the narrow streets are tightly packed with granite-floored, half-timbered houses, and the fire spread rapidly. It was a terrible event – one person died – and the street was sealed off for a month afterwards because of the fumes. They’re still repairing it now. But this was far from the first time that fire had taken hold in the city’s ancient quarter…

The Chapelle Saint-Aurélien, where relics of the patron saint of butchers are held, has a statue of the Christ child eating a kidney. © Ville de Limoges/ Julien Dodinet

In the Great Fire of Limoges in 1864, the rue de la Boucherie was spared, it is believed, because three years earlier a fire had taken out seven houses in the rue du Cheval-Blanc (now rue Gondinet), effectively creating a firebreak. Before that, in 1790, a fire that destroyed 400 houses was stopped just at the bottom end of the quartier de la Boucherie. (It was after that particular fire that the city sensibly founded its fire service, based on the one in Paris.)

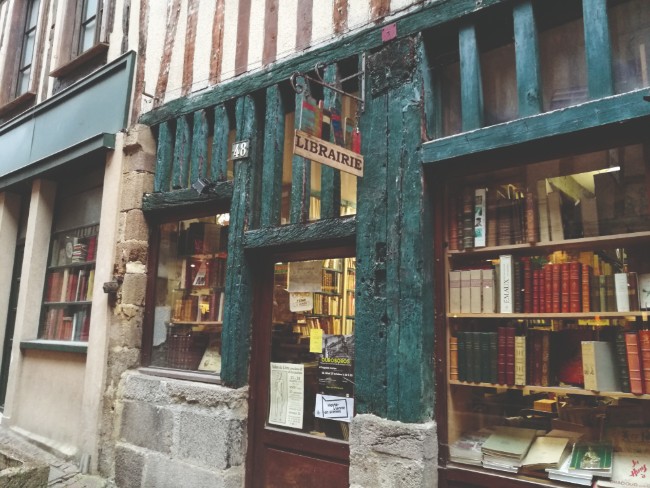

Medieval shop fronts line the streets of the vieille ville. © Jon Palmer

They’ve had similar problems at the cathedral. If you go to the gardens behind it – and you should, they are really quite gorgeous – you will see a spire erected there. This is the old spire of the cathedral. It used to stand on top of the grand church’s distinctively Limousine bell tower, but it was struck by lightning in the 16th century and fell off. They put it back on, but then it was struck by lightning again (yes, apparently it does happen), so they took that as the Will of God and planted it in the garden where it remains, perhaps as a symbol of the city’s resilience.

Behind the cathedral are the city’s botanical gardens. © Vutheara-Tourisme

ARTS OF FIRE

Limoges is known as la cité des arts du feu – though mercifully not for the reasons previously mentioned. Since the Middle Ages, this is where the world’s finest enamel has been made. And making enamel requires fire. Limoges is also, of course, world famous for its porcelain, which again requires fire. It also needs kaolin, which was discovered at nearby Saint-Yrieix-la-Perche in 1769. And it is further famous for its stained-glass windows, the creation of which requires other re-related processes (with which I am, regrettably, not terribly au fait).

Limoges Cathedral windows. © Ville de Limoges Vincent Schrive

The cathedral has Limoges’s best examples of stained glass, as you might expect. While the railway station– inaugurated in 1929 as a replacement for the 1850s original, which had become inadequate to serve a city grown prosperous through porcelain – has magnificent examples in the Art Deco style by Francis Chigot: soft, complementary, pastel hues, as opposed to the bright, sharp colours of the cathedral’s windows. There are a number of railway stations around the world that are recognised for their architectural significance and the Gare de Limoges-Bénédictins is one.

Ornate carvings on the Limoges train station facade. © Ville-de-Limoges/ Vincent Schrive

As well as the windows, and the sculptures by Henri Varenne, it’s also known for its copper roof. The architect was Roger Gonthier, who also designed the Pavillon du Verdurier – the old municipal meat refrigeration centre – which as a building is, I promise you, a lot more poetic than it sounds. Both have domed copper roofs, though the one on the station is now black rather than green. Why? Because it was damaged by fire in February 1998…

The most aesthetically pleasing municipal refrigeration centre you’re ever likely to see is the city’s Pavillon du Verdurier. © Ville de Limoges

PILLAGE AND PLUNDER

We’re going to leave Limoges now and head south, towards Brive-la-Gaillarde. But we’re not going to just blast down the A20, which would take about an hour; we are going to take a wildly circuitous detour, turning off the main road just south of Limoges, by the Limousine Park (a huge, largely cow-related amusement park that is only open in summer), and onto the Route Richard Coeur de Lion. This is going to take us to a number of the region’s many impressive chateaux and churches. And it’s going to take all day.

Limoges station is famous for its Art Deco-style windows. © Jon Palmer

Richard I of England (who was known to the English as Lionheart for his achievements in war, but by a number of less salubrious epithets round these parts for his systematic pillaging and plundering of Limousin) was also King of Aquitaine and Gascony, among various other places. When he was in Limousin, which he was a lot, he liked little more than riding around collecting (some would say stealing) resources for his next crusade or military campaign. This part of France was under English (well, Plantagenet) rule for about 300 years, and it’s not a period of rule the people remember too kindly. Unlike our former king, however, all we’re going to take from here is some photographs and precious memories of the Église abbatiale de Solignac, of the Château de Rochechouart and (on the southern leg of the route) of the Châteaux de Jumilhac, Bonneval and Pompadour. We’ll get to Brive-la-Gaillarde in the evening, after the rush hour has died down – which is a good time to arrive, as you’ll see…

Henri IV in porcelain at Limoges’s Musée national Adrien Dubouché. © Jon Palmer

ANCIENT AND MODERN

Brive-la-Gaillarde is a medium-sized town, the centre of which is medieval, though this part has been developed over the centuries – generally, though, with meticulous care taken to harmoniously marry ancient with modern. Around the centre is a ring road, on which the traffic travels in an anti-clockwise direction. If the roads are clear it doesn’t take more than a quarter of an hour to circumnavigate the town, but if it’s rush hour, it can take forever. Which is why we’ve arrived only just in time for dinner.

Brive centre ville. © Brigitte Beaudesson

The road follows the old ramparts. Brive is called “la gaillarde” – the gallant – because it used to be the best-fortified town in the region. It had good reason to protect itself. This has always been a crossroads of trade, with the routes from Paris to Toulouse and from Lyon to Bordeaux meeting here. The town was actually built to the south of the crossroads, because that area was swampy and unhealthy, yet throughout its 1,000-year history, envious outsiders have sought to penetrate this citadel and remove from it its wealth and source of power.

Collonges-la-rouge. © Jon Palmer

The primordial element here is not fire, as in Limoges, but stone. For this is not only the crossing point of two of France’s most important trade routes, but also the meeting point of distinct geological areas. And it’s good stone, too: the blue slate of Travassac is of such high quality that it was chosen for the 2006 renovation of the Abbey of Mont-Saint-Michel. In the west, the sandstone is pink; to the south, at Collonges-la-Rouge, it is blazing red, courtesy of the high concentrations of iron in the subsoil. And at Tulle, we will see more of the Limousin’s famous granite-floored, half-timbered houses.

This wealth of rock types yields not only excellent mining resources but also a rich and varied agriculture. The beef and veal of the region’s cows are, of course, famous, but so is the lamb and mutton farmed in the south. Then there are the goats used to produce Cabécou cheese; and the ducks that are used to produce foie gras – a commodity for which there are important fairs here in Brive-la-Gaillarde between November and March.

The famous Limousin cow. Photo: Shutterstock

Since the arrival of the railway, producers have also been able to export peaches, apples, strawberries and raspberries, haricot beans and chestnuts; there even used to be a train des petits pois that took peas all the way from here to England.

As it did in Limoges, the railway brought renewed prosperity, and with it the renovation of the old city. They’ve always done this really carefully though, even in the 1980s – in fact, particularly in the 1980s, when one Jean Charbonnel was in charge of the rebuilding of flood-prone quarters that were in danger of falling into ruin.

Limoges’s iconic central station. © Ville de Limoges

Indeed, the seams between ancient and modern architecture here are so carefully stitched that you really need an expert local guide to point them out.

A PEACEFUL SPOT

The 16th-century Hôtel Labenche, built in pink sandstone, is one of the finest Renaissance buildings in the region and is perfectly preserved. This was where visiting royalty and nobility would stay; today it is the town’s art and history museum. Near the 11th-century Collégiale de Saint-Martin, there are Haussmannian buildings. Elsewhere, 15th-century mullioned windows sit happily next to contemporary buildings.

The traffic round the périphérique (ring road) may be awful at times, but within its compass there is peace and quiet and no fear of being knocked into while you are peering upwards at yet another architectural anomaly.

Detail from the door of the Hôtel Lauthonie in Tulle. © Jon Palmer

The same is true at Tulle, where most of the traffic runs along the banks of the Corrèze river and doesn’t interfere with the pretty old town. Tulle is not a big place (about 15,000 inhabitants) but it stretches like a ribbon through the narrow river valley, and if you wanted to see its Musée des Armes (Tulle used to be an important arms-manufacturing centre), right at the western end of the town, and the Maugein factory over the river (the last place in France where accordions are still made), you might consider giving up your precious parking place for the excursion.

Tulle’s Maison Loyac is a flamboyant Gothic affair dating from the 16th century. © OT Tulle en Corrèze

The centre is eminently manageable though. The Cathédrale Notre-Dame is unmissable, as are its adjoining cloisters and the municipal museum above. To the side of the cathedral is the place Gambetta, with the richly-decorated Maison Loyac and, nearby, the Renaissance façade of the Hôtel Lauthonie. Wandering up from here into the medieval heart of the old town is to be encouraged, as is a cold drink on a café terrace on rue Barrière when you’re done.

From Tulle, we would like to venture up into Limousin’s third département, Creuse, through the Parc naturel régional de Millevaches to Aubusson and beyond… But the weather has turned and we will instead go left at Aubusson and return to Limoges. We’ve run out of time. I blame Richard the Lionheart.

From France Today magazine

The Église Saint-Michel-des-Lions in Limoges. © Ville de Limoges/ Thierry Laporte

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

By Jon Palmer

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *