Claude Monet & Gustave Caillebotte: Painters, Gardeners and Best of Friends

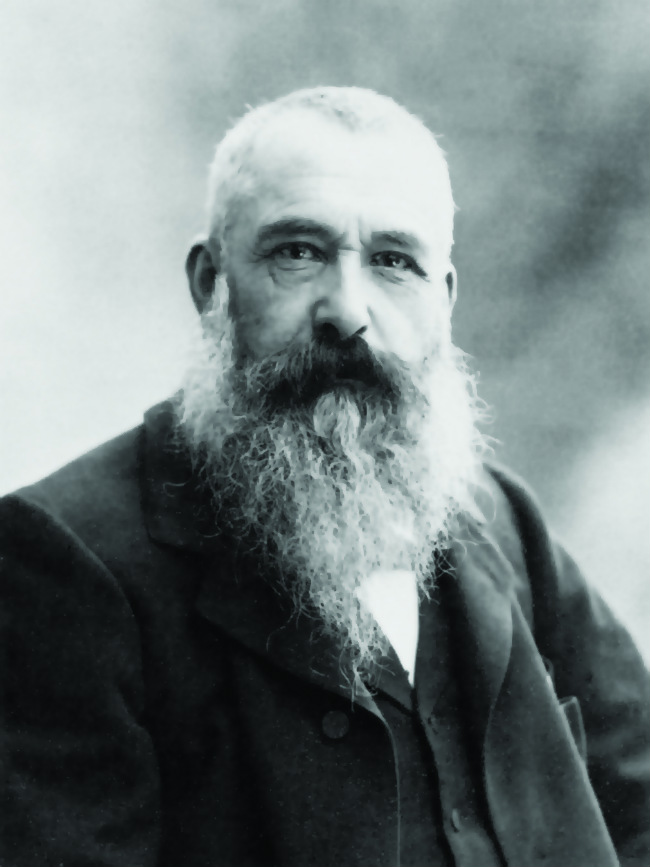

“If he had lived instead of dying prematurely, he would have enjoyed the same upturn in fortunes as we did, for he was full of talent. He was as gifted as he was conscientious and when we lost him he was still at the beginning of his career.” — Claude Monet writing about his friend Gustave Caillebotte

The Musée des Impressionnismes in Giverny recently had an exhibition focusing on Gustave Caillebotte, the talented painter who was a patron, organiser, collector and recognized member of the Impressionist movement. I took the opportunity to visit Giverny this spring to see Monet’s garden, and to catch the exhibition.

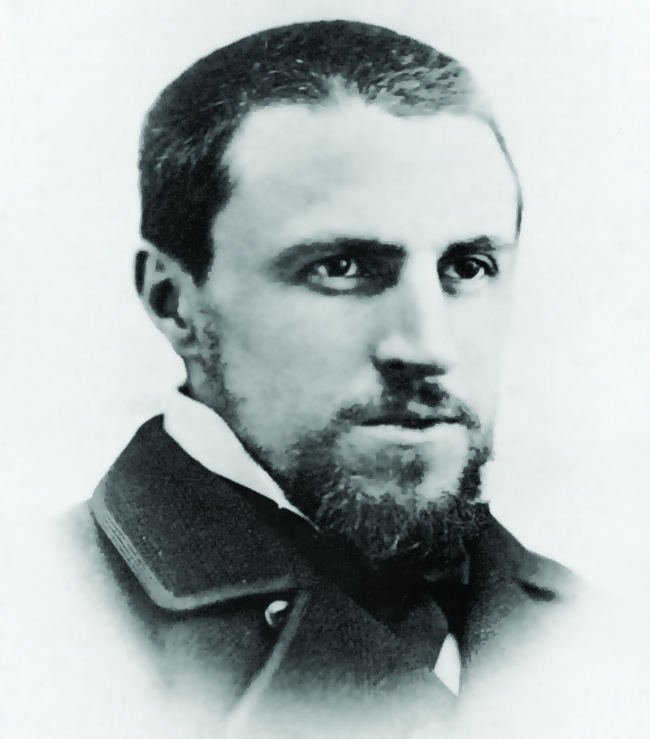

It is only in recent years that Caillebotte has begun to shake off his reputation as the amateur painter who merely played a supporting role for the ‘true’ Impressionists. Born into a well-heeled Parisian family in 1848, he inherited the family fortune at the age of 26, just a few years after he developed his interest in painting. Such substantial wealth at an early age must have proved both a blessing and a curse on his career, and influenced how he would be perceived by later generations.

Caillebotte’s

Paris Street, Rainy Day

Impressionist Influence

A visit to the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874 had a profound effect on the young painter, and his early works bear the hallmarks of Impressionist influence. It was in the same year that he began to meet some of the other notable painters, including Degas, whose studied Réalisme may have influenced Caillebotte’s early works such as Les Raboteurs de parquet (The Floor Planers). This was among six works exhibited at the second Impressionism exhibition, to which Caillebotte had been invited by Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Henri Rouart.

With the confidence of his inherited wealth behind him, the young Caillebotte had the time and enthusiasm to befriend and support other painters in the early Impressionist movement. With no pressure to earn money selling his own paintings, he and his brother Martial bought a large apartment in Paris where Gustave was free to paint whatever subject matter he wished. He did not have to look far for inspiration – the period from 1875-1880 is notable for his iconic paintings of Haussmannian street scenes in Paris (such as Rue de Paris, temps de pluie) with their muted grey-brown tones. Although these have a strong undercurrent of Realism, the young artist was unafraid to experiment with more radical shifts of perspective. For example in Boulevard vu d’en haut, the unusual perspective is from a balcony straight down through the canopy of trees onto the heads and shoulders of pedestrians at pavement level.

In 1875 Caillebotte purchased an early Monet, and from then on his acquisitive instincts took flight and he began to collect more and more paintings of fellow Impressionists. (There were nearly 70 paintings in his estate when he died, including 16 by Monet.) He also became a regular exhibitor and supporter of group events in Paris, and later in New York and Brussels. He wrote often to Monet, encouraging his friend to paint and to exhibit – in February 1879, “Mettez le plus de toiles que vous pourrez.” (“Exhibit as many paintings as you can.”)

Caillebotte’s Richard

Gallo and his Dog, Dick, at Petit-Gennevilliers

The Sailing Gardener

In 1881 the Caillebotte brothers bought a house in Petit Gennevilliers, across the River Seine from Argenteuil, where Monet had lived and painted the regattas and the famous bridge. And from this time forward, Gustave’s passion for painting is joined by two new enthusiasms: sailing and gardening. Caillebotte’s abilities as a sailor and innovative boat and yacht designer merit a chapter all to themselves, but further serve to demonstrate how he must have been a man of rare energy as well as imagination.

With memories of their country childhood in the grand family house and gardens at Yerre, the brothers set about extending the house at Petit Gennevilliers, gradually acquiring more plots of land and building a large greenhouse.

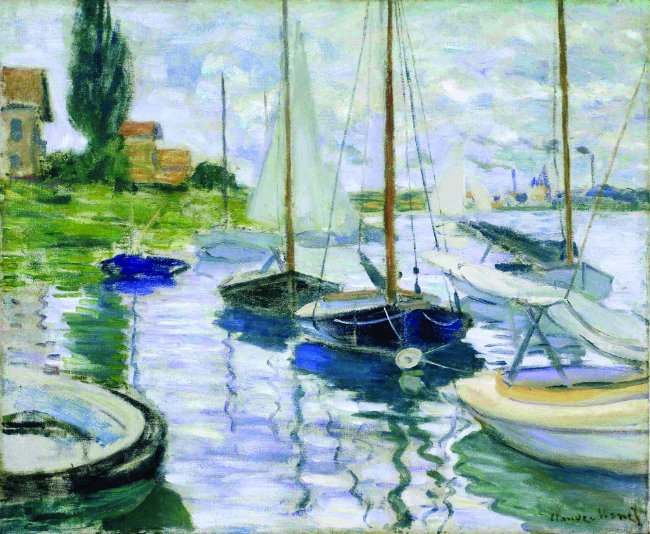

In Caillebotte’s work from this period there emerges a looser, softer style of painting. How could he not have been influenced by Monet’s style, both as collector and as moral and financial supporter? The similarity is striking in the paintings of the waterways around Argenteuil, in the confident brush strokes of Linge séchant and the flecked, dappled apple blossom of Vergers aux pommiers en fleur.

Claude Monet’s “Boats Moored at Le Petit-Gennevilliers”

During the 1880s, Caillebotte and Monet were in touch regularly and Caillebotte often wrote to share with Monet his appreciation for the beauty of the countryside and the natural world, his frustrations at the weather, and his challenges in trying to balance the demands of travelling for his yacht-racing with finding time for painting. With Giverny also on the River Seine, Caillebotte would have been able to sail his boat downstream to visit his friend.

The blossoming of the abundant gardens at Petit Gennevilliers coincides with Caillebotte’s most fertile period. Each year the gardens exploded into a blaze of colour, creating an earthly paradise and an inspiration for the artist. When his brother Martial got married and moved away, Gustave bought out his share of the property and acquired more land. As would Monet later at Giverny, so Petit Gennevilliers and its gardens became more and more the focus of the painter’s time and attention, a passion he shared with Monet in writing, talking about his new greenhouse and intricate systems for irrigating the plants.

Rose Garden at Giverny. © ARIANE CAUDERLIER, GIVERNY IMPRESSION.COM

Flowering Passion

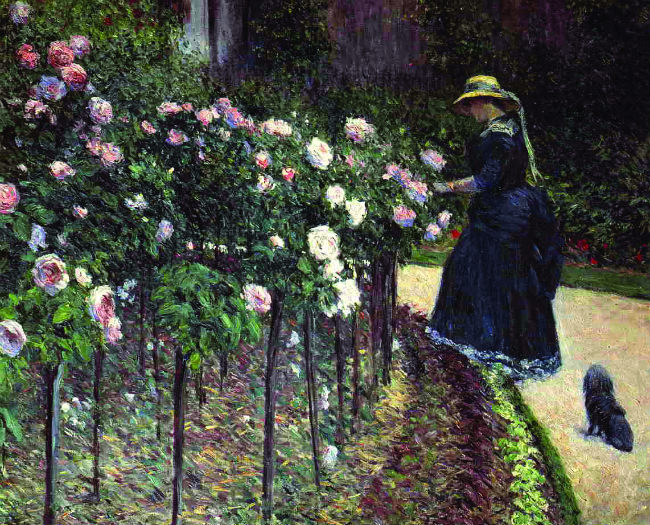

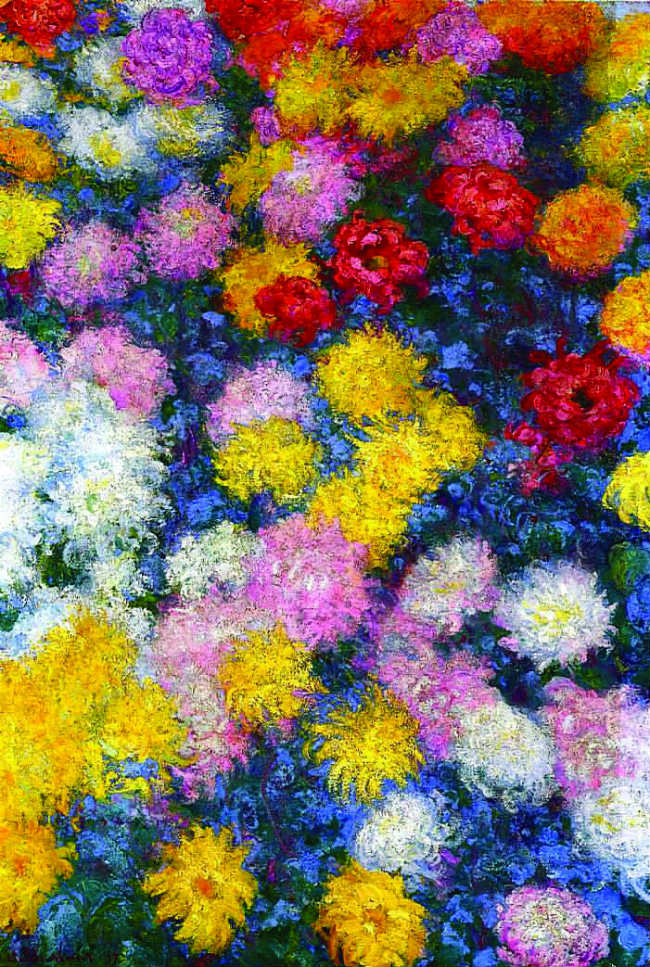

From this period on, the subject matter of Caillebotte’s paintings is increasingly drawn from the intimate garden world he has created with chrysanthemums, dahlias, irises, marguerites, nasturtiums, orchids, gladioli, sunflowers and roses. In this respect the two painters seem closer than ever, yet in fact Caillebotte’s enthusiasm for nature largely pre-dates Monet’s – this was well before the time of the Nymphéas. Monet’s Massif de chrysanthemes in 1897 echoes the earlier paintings by Caillebotte, and on Monet’s bedroom wall at Giverny is Caillebotte’s own White and Yellow Chrysanthemums, from 1893.

Gustave Caillebotte’s

“Sunflowers, Garden at

Petit Gennevilliers”

The attention to flowers and painting is almost obsessive. Caillebotte writes a note of apology to Monet, cancelling their lunch: “I am growing a stanhopea aurea (an orchid) which has been in flower since this morning. The flowers only last three or four days, and will not bloom again for another year. I cannot let it go. My apologies…”

Not content with creating a version of Eden in his garden, the enthusiast Caillebotte wanted to bring the garden into the house. On display at the exhibition in Giverny were the painted panelled doors which Caillebotte created for his dining room, echoing Monet’s painted doors for the great patron and gallery owner Paul Durand Ruel.

Roses and irises in Monet’s Garden. © ARIANE CAUDERLIER, GIVERNY IMPRESSION.COM

Today, Monet’s Clos Normand flower garden in Giverny offers the closest reflection of what Caillebotte’s might have been. In the last few years the gardens have been revitalised under the direction of British head gardener James Priest, whose ambition has been to bring a painterly quality to the choice of colour in the formal areas. Caillebotte would have surely enjoyed the geometric layouts with their echoes of classic parterres, yet heavily planted with annuals and perennials carefully nurtured and designed to create resplendent waves of graduated colour tones. At Petit Gennevilliers many of the same plants would have been grown: tulips, chrysanthemums, dahlias and roses. Caillebotte’s Allée de jardin et massifs de dahlias gives a sense of the formal structure of the paths lined with towering dahlias and Les roses, jardin du Petit Gennevilliers evokes the sheer romance of the cordons of pink roses.

Caillebotte’s Roses in the Garden at Petit-Gennevilliers

Thanks to the clever succession of planting at Monet’s garden, a visit at almost any time of year from spring to autumn is guaranteed to offer a colourful display. When you visit Monet’s house next time, look on the walls of his bedroom, where you can see some of the paintings (albeit copies) that Caillebotte gave to his fellow painter, gardener and friend.

Sadly, unlike the wonderful gardens at Giverny, which have survived to become a kind of pilgrimage destination, of Gustave Caillebotte’s garden nothing remains. We only have a few rare photographs, some correspondence and the paintings themselves to be our guide. The site was gradually industrialised and then destroyed by bombing during the Second World War – it has been completely obliterated.

Gustave Caillebotte. © RMN-Grand Palais musée d’Orsay Photo Martine Beck-Coppola

A Strange Legacy

Aside from the valuable oeuvre of Caillebotte’s own paintings (many of which are in private hands as the major museums were late to the party), there was another unrivalled legacy of paintings, the story of which contains an ironic twist.

In 1876, following the premature death of a younger brother, Caillebotte drew up a will in which he left all his paintings (including those he acquired from fellow Impressionists) to the French state – a noble gesture for a young man of just 30. But there was a catch – two catches in fact. First, in a moment of extraordinary prescience, he insisted that there should be a period of perhaps 20 years before they be displayed – “jusqu’à que le public, je ne dis pas comprenne, mais admette cette peinture,” – “until the public, even if they don’t understand them, at least accepts these paintings.” Secondly, with some bravura, he also insisted that they should not be displayed at any provincial museums, only at the Luxembourg or, later, at the Louvre.

Portrait of Claude Monet

Appreciating Assets

And so it was that, when he died prematurely, aged 45, in February 1894, he left to the French state an accumulated collection of no fewer than 68 paintings, including masterful works by Monet, Cézanne, Degas, Sisley, Renoir, Manet, Pissarro and Millet. Yet, even though by the turn of the century there was a growing appreciation for the art of the Impressionists, such appreciation did not extend to the administrators of the French state, who were somewhat embarrassed by the bequest and reluctant to donate large amounts of gallery space to it. Yet Renoir, who was Caillebotte’s executor, pressed the matter and eventually space was found for some of the paintings, though 28 were refused. It wasn’t until some decades later that tastes changed and the new guardians of the French art establishment looked afresh at the extraordinary legacy. In 1928 they made an attempt to reclaim the other 28 but were rebutted by Caillebotte’s heirs and the works were eventually sold privately. Today, these original paintings from Caillebotte’s legacy form the precious core of the Musée d’Orsay’s Impressionist collection. Curiously, none of the artist’s own works were amongst the legacy.

The museums were late to appreciate the works of Gustave Caillebotte and many have ended up in private hands, so don’t miss the chance to view the work of this under-appreciated Impressionist if an exhibition comes your way.

With acknowledgements to Marina Ferretti Bocquillon, author of Gustave Caillebotte, Peintre et Jardinier

The Garden at Petit Gennevilliers, 1893 by Gustave Caillebotte

Giverny Essentials

WHERE TO STAY AND EAT

Les Jardins des Plumes, Hotel and Restaurant: This grand house in Giverny village has been transformed into a stylish hotel. Its restaurant operates under Michelin-star chef Eric Guerin in a room where Art Deco meets contemporary. The hotel has four suites in the main house and four in the atelier in the garden. www.jardindesplumes.fr

There are many chambres d’hôtes in Giverny, such as Les Jardins d’Hélène. www.giverny-lesjardinsdhelene.com

On the hills above Giverny is La Réserve, a gorgeous maison d’hôtes surrounded by woodland and orchards, with five bedrooms and a cottage. www.giverny-lareserve.com

Maison Baudy, Restaurant: This characterful inn was a gathering place for Monet’s friends and visiting artists, including Renoir, Sisley, Cassatt and Cézanne. It serves classic French dishes in a quaint, traditional dining atmosphere, and features a rose garden, an outside terrace and an artist’s gallery. www.restaurantbaudy.com

CONTACT

Fondation Claude Monet, Monet’s House & Gardens: 84 rue Claude Monet, 27620 Giverny. Tel: +33 02 32 51 28 21. [email protected]. www.claude-monet-giverny.fr

Musée des Impressionismes: 99 rue Claude Monet, 27620 Giverny. Tel: +33 02 32 51 94 65. [email protected]. www.mdig.fr

From France Today magazine

Monet’s “Chrysanthemums”

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

By Guy Hibbert

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY