Great Destinations: Île-de-France, Haunt of Kings and Artists

There is more to Île-de-France than just Paris. Proud Francilienne Marion Sauvebois ventures out of the capital to discover the picturesque villages that charmed the Impressionists, before going château-hopping and hitting the dance floor at a riverside guinguette…

As I inch up the creaky staircase to the attic of Auberge Ravoux, I picture Vincent van Gogh staggering up these very steps 127 years ago today, gasping from the effort, hands clutching his chest. On 27 July 1890, the painter shot himself in a nearby wheatfield, but wasn’t killed outright.

Van Gogh’s “Champ de blé aux Corbeaux”, 1890

He stumbled back to his room at the inn, the bullet lodged below his heart, and stoically waited for death. Peering inside the chambre de Van Gogh, the stark little room illuminated by a single shaft filtering through the minuscule skylight seems frozen in time – thanks, in part, to superstition. Renting out the room of a suicidé was considered bad luck, so the artist’s cramped hovel in Auvers-sur-Oise was left untouched for close to a century.

A field of colza in Auvers-sur-Oise. Photo: Martinelli

“There is nothing to see here,” warned Dominique Charles Janssens, President of the Institut Van Gogh, before our ascent. “But everything to feel,” added the mastermind behind the Auberge Ravoux, now known as the House of Van Gogh.

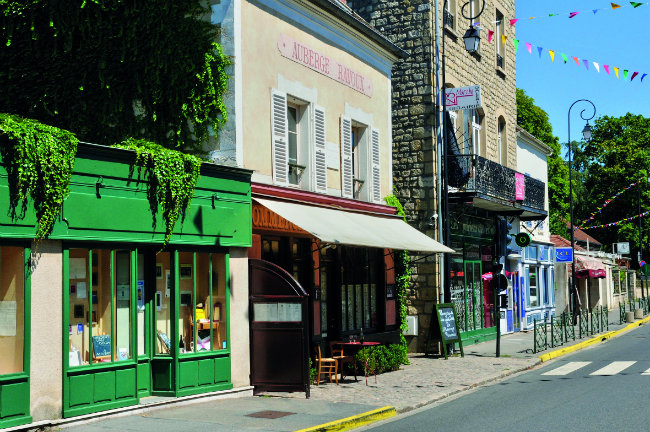

Auberge Ravoux. Photo: Fotolia

Devoid of any furniture except for a lonely straw chair, there are no paintings (although Dominique has grand plans to remedy this) and no visible reminders in the 7m2 shoebox of his final days in the sleepy village. Yet something intangible pervades the atmosphere. As I tiptoe in, feeling like a trespasser, I am completely lost for words. Dominique doesn’t bat an eyelid. He has seen statesmen and a roster of fearsome chief executives dumbstruck at the sight of the artist’s bare lodgings.

He recalls how director Roman Polanski dropped in one night for a spot of supper at the inn’s 19th-century style bistro, but refused categorically to bother with a look-in on la chambre. His arm firmly twisted, he finally scaled the few steps to the attic. “By the end, he was hugging me with tears in his eyes,” Dominique smiles.

Dining room at the Auberge Ravoux. Photo: Erik Hesmerg

A self-professed guardian of the painter’s legacy, Dominique is no art historian and, until a drunk driver rammed into his car outside Auberge Ravoux 32 years ago, had never given Van Gogh more than a passing thought. During his convalescence, he devoured the Impressionist’s correspondence and discovered the life of a creative genius at odds with the myth of the insane whoremonger who severed his own ear.

Van Gogh lies in an ivy-covered grave next to his brother in the cemetery in Auvers

Recovered, Dominique quit his marketing job, bought the Auberge Ravoux and set about creating a shrine of sorts, a “place of memory”, offering select visitors a rare glimpse into the artist’s intimacy, in the small nook of Île-de-France where he enjoyed his most productive period, painting more than 70 works in 70 days.

The church in Auvers-sur-Oise. Photo: Fotolia

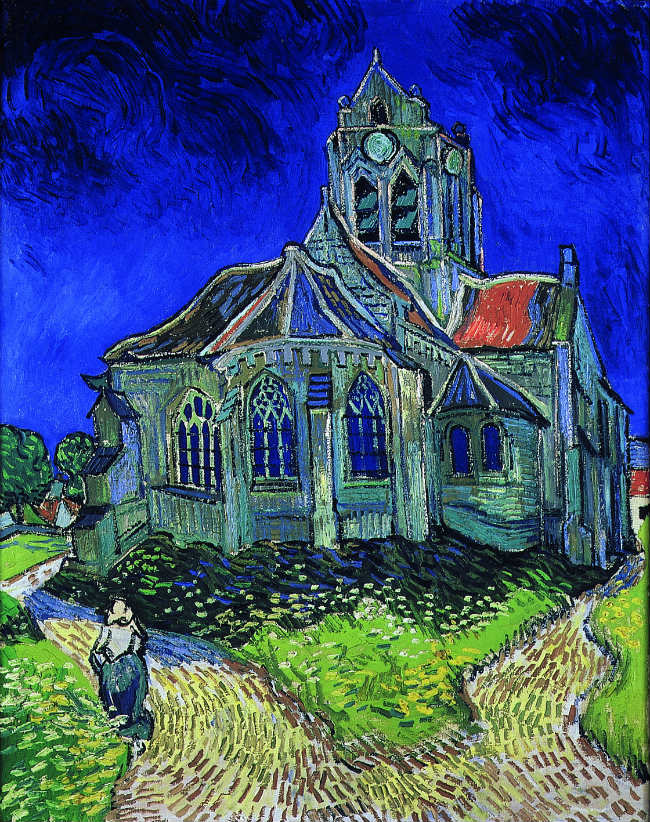

Weaving around Auvers’s warren of postcard-perfect streets and chocolate-box cottages, it is easy to see what enticed Van Gogh (and indeed a coterie of artists) away from the clamour of the capital to this rural idyll in the heart of Île-de-France. Today, thousands of ‘pilgrims’ (some bearing posies – others, disturbingly, loved ones’ ashes to scatter at the Impressionist’s grave) wind their way around the village each year to pay homage to the master. Like them, I hop on the Van Gogh trail, pausing by each reproduction marking the spot where he put down his easel on his frenzied creative spree: the village church; the home of his dear friend and physician Dr Gachet; and the golden champs de blé of Wheatfield with Crows, amid which he attempted suicide. On this bright summer’s day, it is nearly impossible to imagine the fatally-wounded painter scrambling through the chaff. And yet the looming walls of the cemetery in the distance, where he rests under a tangle of ivy next to his brother, are a sobering reminder of his untimely end.

Van Gogh’s “L’Eglise d’Auvers-sur-Oise”, 1890

But Van Gogh is by no means the only artist to have sought out the bucolic charms of the outskirts. The whole of Île-de-France, I was soon to discover, is one never-ending (Pre)-Impressionist art trail.

And while Auvers has become synonymous with the tortured painter’s final days, to its denizens it is, and always will be, the stronghold of the forefather of Impressionism, Charles-François Daubigny – whose studio is open to the public. An admired artist in his time and bigwig of the Salon, before he distanced himself from the Academy, he was among the first to lay down roots in Île-de-France; long before Van Gogh set foot in Auvers. And crucially, he was the first to execute a ‘fresh air’ painting, heralding the beginnings of Impressionism.

The room where Van Gogh died in at the Auberge Ravoux. Photo: Joe Cornish

THE MAVERICKS OF BARBIZON

As early as 1840, a group of painters sidelined by the Art Salon set up a colony in the village of Barbizon, most of them boarding at the affordable and rather laid-back Auberge Ganne on the edge of the forest of Fontainebleau. Its tolerant owners, the Gannes, gave them free rein to use – or perhaps gave up trying to curb their unbridled use of – the building and furniture as blank canvasses; many of their guests being too strapped to afford art supplies.

L’Auberge Ganne. Photo: Marion Sauvebois

And to this day, the inn remains a blissful riot of frescos, trompe l’oeil and sketches creeping up the walls. A cartoonish Pinocchio beckons to visitors from a corner of the old dormitories while a quick sweep of the room reveals a spooky figure glowering from a mantle-top. But it is the face of an adorable mutt etched again and again around the Auberge, now the Museum of the Barbizon School, that catches my eye. “It’s Ronflot, the innkeepers’ dog,” my guide Wafaa answers my unspoken question.

L’Auberge Ganne is now the Barbizon School Museum. Photo: Marion Sauvebois

The cute hound was the mascot of the cradle of Pre-Impressionism and a willing model to the starving artists of the growing School of Barbizon (as it is now known). Under the stewardship of standard-bearers Théodore Rousseau, aka “l’éternel refusé”, and Jean-François Millet, who took up permanent residence down the road, the merry band of mavericks found inspiration in Seine-et-Marne’s landscapes. There, they broke the classical mould, capturing nature’s peculiar beauty and prosaic rural scenes.

The walls of the auberge are dotted with sketches. Photo: Marion Sauvebois

Now a wondrous memento, the former inn tells a story of struggling artists spurred on by an unfailing faith in their art and unflagging camaraderie. A pipe on the sideboard reminds us of the friendly hazing meted out to each new arrival. They were asked to smoke and the plume’s colour would reveal their true mettle as a painter: one of the moderns, or one of the old Beaux-Arts farts. Though, as far as Wafaa is aware, no-one was ever shown the door based on a puff of smoke. Many of these now anonymous visionaries paved the way, not unlike Daubigny, for such painters as Monet, Renoir and Sisley to hone a fresh and bold perspective on landscape.

Ronflot, the model dog. Photo: Marion Sauvebois

THE CURSED IMPRESSIONIST

Alfred Sisley, too, felt the pull of the banlieue. And for 20 tumultuous years, punctuated by endless rejection and bouts of depression, he sought inspiration in the medieval town of Moret-sur-Loing (the birthplace of sucre d’orge, or barley sugar sweets), on the banks of the Loing River. Buoyed by his friend Monet, the “Cursed Impressionist” – art historians certainly have a taste for the dramatic – scoured its cobbled lanes in search of material and dedicated many paintings to the grand Notre-Dame church towering over the main thoroughfare. Again, reproductions of his paintings form a loop around Moret, signposting the sights he committed to canvas. His is a story of bad timing. While he struggled to pique the interest of the art world in life, he earned lasting recognition less than a year after his death; thanks to Monet, who organised an exhibition of his works at which every last painting sold. The English landscape artist was also granted French nationality just days after he succumbed to throat cancer. He could, as Wafaa puts it diplomatically, “never catch a break. But he never lost hope, none of the Impressionists did and history eventually proved them right.”

Moret-sur-Loing. Photo: Fotolia

VALLEY OF CHÂTEAUX 2.0

Long before it was reclaimed as the stomping ground of penniless artists, Île-de-France was a favourite haunt of monarchs and the elite. And with nigh on 300 châteaux dotted across seven départements – not including Paris’s own palatial contingent – the region could give the Loire a run for the title of ‘Valley of Châteaux’. The Petite Couronne (a rather apt moniker for the Paris region) is veritably teeming with Renaissance, baroque and neoclassical confections (plus the odd ruin), with extravagant gardens to match. We have obsequious courtiers, who favoured a pied-à-terre within a quick canter of their king, to thank for this abundant legacy. Though some – such as Nicolas Fouquet, the disgraced visionary behind the Château de Vaux-le-Vicomte – would have done well to keep a healthy distance.

Vaux-le-Vicomte

A marvel to behold, Vaux-le-Vicomte is undoubtedly one of the grandest palaces in Seine-et-Marne – belying the département’s unfair reputation as woefully inferior to its neighbours (even among Paris’s cousins, there’s a strict pecking order). No surprise there, as Fouquet spared no expense; a profligacy the Superintendent of Finances surely came to regret. By the time he unveiled his lavish estate at a party in honour of King Louis XIV in 1661, court machinations had already begun to poison the monarch against him. And this display of wealth was the final straw. The Sun King had his minister imprisoned for life for embezzlement of crown funds. In a masterstroke, Louis XIV recruited the three artists behind Vaux-le-Vicomte to outdo his dishonoured subject and build the most extravagant palace ever dreamt up, at Versailles – though many argue it never quite surpassed the original.

The Chateau de Versailles. Photo: Christian Milet

Paradoxically, perhaps, it is away from its exalted halls and conspicuous opulence that Versailles truly comes alive. Idling along the lattice of gardens as fountains gush into life to the backdrop of baroque music is the pinnacle of any visit, and brings home the artistry of the domaine. But the real pièce de résistance is the Hameau de la Reine. The quaint ‘model village’ nestling on the edge of the grounds was Marie Antoinette’s refuge from court intrigue, and provides an intimate window into the queen’s private life.

Like countless crowned heads before her, Marie Antoinette was also fond of escaping to the royal country residence of Fontainebleau, whose tranquil forest beguiled monarchs centuries before it became an artists’ retreat. Francis I laid the first stones of the current palace, while incorrigible philanderer Henry IV’s trysts there are legend. It was here that Napoleon I abdicated (first time around), and later attempted (and failed) to poison himself. Decidedly less grand, but frankly more fun, the Château de Breteuil in the Chevreuse Valley has made a name for itself as the home of the kitsch Charles Perrault Fairytale Trail, which celebrates the yarn of one of its most famous guests with wacky tableaux of Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty and co. Perrault aside, the pile has another claim to fame: as the summer host to the future king Edward VII, who was shuttled off to Île-de-France to better his French. If you ask politely, you may get to peek at the letters exchanged between the Breteuils and Windsors, as the British King and Queen checked their young son behaved himself.

Prisoners were held in the donjon at Vincennes Château. Photo: P.Cadet, CMN Paris

Speaking of being naughty, the Château de Vincennes’s seedy past as a prison makes for a juicy recce. Once a royal fortress abutting Paris, it boasts the highest medieval keep in Europe, and a motley crew of noble inmates. Enlightenment philosopher Diderot and Fouquet both did time here, as did the Marquis de Sade – who was so insufferable he was exiled to the ground floor to give fellow prisoners a little peace.

The detainees being of noble birth, the concept of ‘loss of freedom’ did not quite bed in. They would blithely walk out for tête-à-tête with harlots, were allowed their own caterers and to decorate their quarters as they saw fit (ornate friezes on the bare stone are still visible today). Its most notorious inmate is no doubt the Duke of Beaufort, who engineered such a “heroic breakout” in the 17th century, he was actually pardoned and set free.

OFF TO THE GUINGUETTE

No jaunt to the banlieue is complete without a spin at the guinguette; so named after the guinguet, the local sour white wine. The joyful preserve of Île-de-France (despite originating in Paris), the guinguettes are a throwback to simpler times; when petit blanc flowed and hordes of harried workers, artists and other misfits flocked to these outdoor café-restaurant-dance hall hybrids on the banks of the Marne for a little farniente on a Sunday. Caillebotte, Manet and Monet were all known to patronise the guinguettes.

It may as well be the early 1900s as I cross the footbridge to the Guinguette de l’Île du Martin Pêcheur on the banks of the Marne to the din of wine-fuelled laughter and accordion. Inside, elderly couples are tearing up the dance floor. One particularly dapper gent in shiny spats is giving a blushing teen – in a tube top – a twirl.

The historic guingettes in the Paris region

In the 20th century, thanks in no small part to the opening of the Pathé film studios in nearby Joinville, rising stars like Simone Signoret took to mixing with the locals at the guinguettes, imbuing these humble watering holes with movie glamour. As many as 200 lured punters to the meanders of the Marne in their heyday. But by the 1960s and 70s, they had fallen out of favour. One of them, Chez Gégène, the oldest surviving guinguette and a Val-de-Marne institution, bucked the trend though. In fact, it was one of the few not to close during the Occupation, although dancing was banned. But thanks to a bout of ye-old-days nostalgia, the tradition has been revived and Franciliens are swarming once more to the Marne for a merry time at the likes of Champigny’s Guinguette de l’Île du Martin Pêcheur, whose annual Miss Guinguette pageant never fails to grab headlines. The recently-crowned Miss is nowhere to be seen, but her majesty’s absence has not dampened patrons’ moods one bit.

As liquid courage works its heady magic, I join them on the crammed dance floor. Hobbling away huffing and puffing after just once waltz, I am reminded of Wafaa’s parting words. “People, not just artists, flocked to the region because they were looking for something – a quality of life, excitement, inspiration – they just couldn’t find in Paris.”

It still holds true today.

From France Today magazine

Revellers soak up the atmosphere at the Guinguette de l’Île du Martin Pêcheur. Photo: Marion Sauvebois

Share to: Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Leave a reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

REPLY